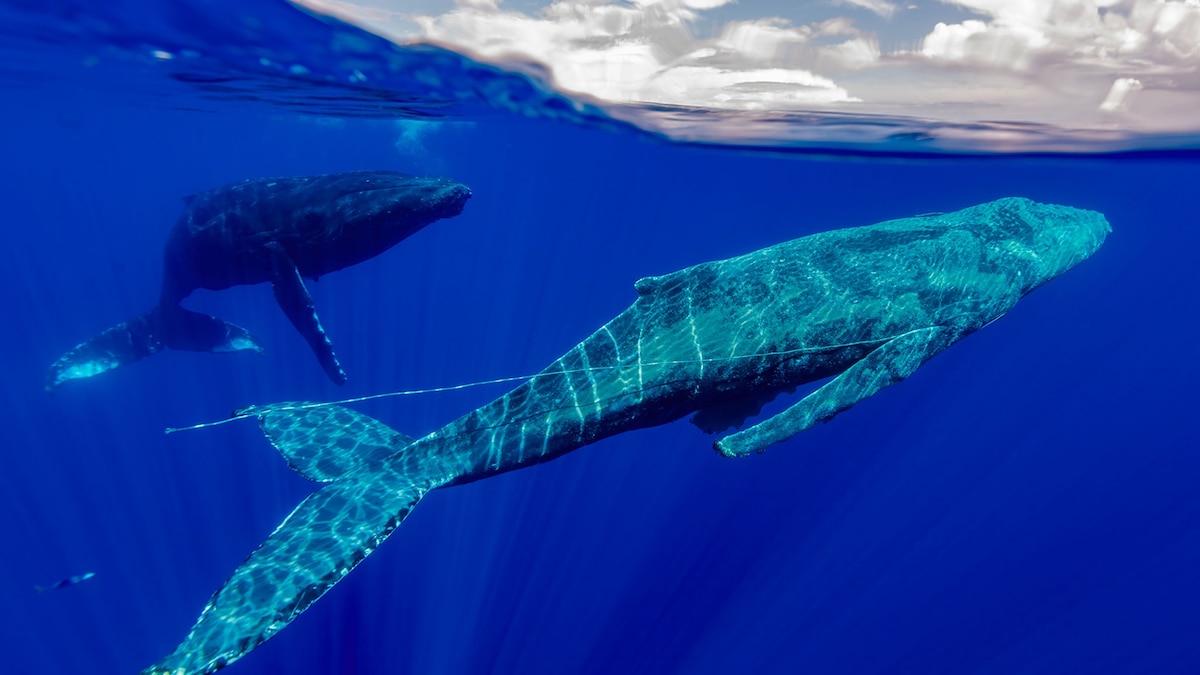

Now Reading: Humpback Whales Rally to Free Entangled Companions

-

01

Humpback Whales Rally to Free Entangled Companions

Humpback Whales Rally to Free Entangled Companions

Speedy Summary:

- Research led by Rachel Cartwright at California State University documented “companion whales” assisting entangled humpbacks in fishing gear.

- A notable example involved an adult teaching a young whale too use tail-fluke movements to free itself from entanglement.

- In another case, an adult male helped a trapped two-year-old female by keeping her buoyant and fending off tiger sharks.

- Data spanning 2001-2023 showed 62 instances of companion whales aiding others out of 414 reported entanglements in Hawaii and Alaska combined. Assistance was observed between both juvenile-adult and adult-adult pairs.

- Historically, similar behaviors were noted during whaling eras despite risks to helper whales.This empathy-driven trait may be tied to affective empathy or behavioral adaptability due to frequent modern-day threats like fishing gear entanglement.

- Entanglement in fishing equipment affects over 80% of whales during their lifetimes, with up to 25% facing it annually before self-releasing.

- Conservationists emphasize reducing marine gear risks through better technologies like rope-free or minimal-line tools as critical preventive measures.

Indian Opinion Analysis:

The study highlights the complex emotional and social intelligence among humpback whales, which could reshape how humans perceive marine mammals’ capacities for empathy. The documented rise in such behavior correlates with increased human-induced environmental stressors like widespread gear entanglements. For India-a nation with expansive coastal ecosystems and active fisheries-the findings are vital reminders about balancing maritime industries with marine life conservation.

India’s challenge lies in adopting sustainable practices that mitigate harm while securing livelihoods tied to its seas. Exploring technologies like eco-friendly or reduced-risk fishing equipment can not only foster biodiversity but also strengthen the global push for oceanic sustainability ahead of climate shifts impacting all nations’ aquatic resources.