Now Reading: How a single battle—and one young pharaoh—turned Egypt into a superpower

-

01

How a single battle—and one young pharaoh—turned Egypt into a superpower

How a single battle—and one young pharaoh—turned Egypt into a superpower

The death of Queen Hatshepsut opened the door to rebellion in the Levant. After 22 years in power, she disappeared from history and Thutmose III occupied the throne of Egypt alone. A coalition of Canaanite city-states, supported by the Mitanni Empire and rulers of Kadesh, began to rebel against the new pharaoh. It would come to a head in the walled city of Megiddo, in what today is Israel. Sited on the Plain of Esdraelon, the city could control two trade routes of special interest: one connecting with the coastline and the other leading north to Kadesh. As this was Thutmose’s first military campaign, the pressure on him was considerable.

POWER OF THE PREDECESSORQueen Hatshepsut (center), Thutmose III’s predecessor and stepmother, kneels before Amun-Re (left) to receive a blessing in this relief in the Temple of Amun-Re at Karnak, Egypt.

SCALA, FLORENCE

The route to Megiddo

According to the large propaganda inscription on the walls of Akh Menu (the Temple of Thutmose III at Karnak), the young pharaoh gathered his men and started marching from the border fortress of Tjaru in the eastern delta to face that powerful enemy. There is no direct information on the number of soldiers mobilized, although most scholars estimate they probably numbered in the thousands. Nor is it known if the entire army set out from Egypt or if units that were already stationed in Asian territory were incorporated later.

(Is there really a secret city under Egypt’s pyramids?)

It took 10 days for the troops to travel the so-called Way of Horus, north of Sinai, and reach Gaza. The distance is around 125 miles, which indicates that the soldiers marched an average of 12.5 miles a day. From Gaza they advanced to the enclave of Yehem, about 25 miles from Megiddo. There the pharaoh met with his officers to assess the situation and decide which of the three existing routes to Megiddo would be the most suitable. The northern route crossed the lands of Zefti; the southern route would take them close to Taanach; the central and most dangerous route would send them through the narrow Aruna pass. The Annals of Thutmose III, a propagandistic record of his military campaigns inscribed in the Temple of Amun-Re at Karnak, details how Thutmose handles the decision.

This graywacke statue of Thutmose III depicts the king wearing the nemes (royal headdress) with the uraeus (protective cobra of the pharaohs) on his forehead. Museum of Luxor, Egypt.

KENNETH GARRETT

His generals urged him not to make them take the Aruna pass. “Let our victorious Lord march by the road he wishes; but let him not oblige us to go by the (most) perilous route.”

But Thutmose was determined to defy his enemies and, by taking the most dangerous route, show that he didn’t fear them. He swore an oath by the sun god Amun-Re, saying: “My Majesty will march by this Aruna Road!” He also determined that he himself would lead the army through the narrow pass. “None shall march on this road in front of my Majesty and (when the time came) he himself did march at the head of his army, showing the way with his own steps.” The route he chose was just over eight miles long, with parts of it only 30 feet wide. With steep walls on either side, it was the perfect place for the enemy to ambush an advancing army from above, as there was no room for maneuver. However, assuming the Egyptians would never risk such reckless exposure, the enemy had only stationed soldiers on the other two paths. Thutmose’s army was able to march the route through the Aruna pass in one day without any problem. The soldiers emerged into the Qina valley to the astonishment of enemy troops who were encamped near the city of Megiddo.

(The last missing tomb from this wealthy Egyptian dynasty has been found)

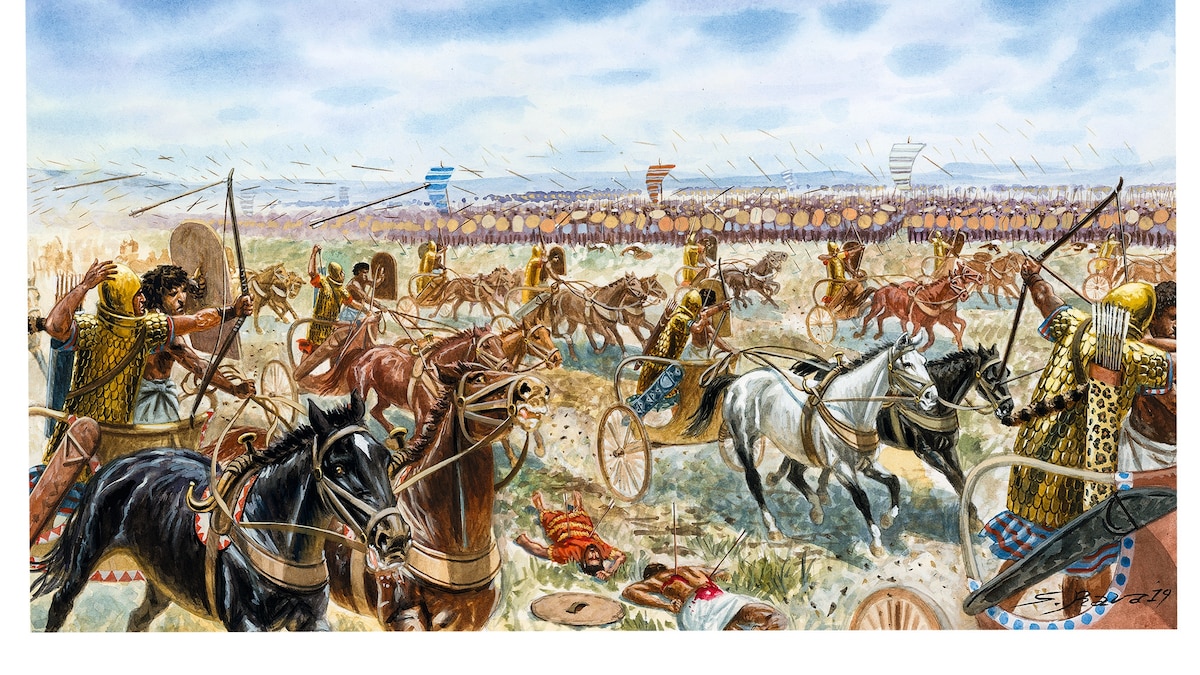

The Egyptian advance

At dawn the following day the Egyptian army was mobilized, dividing and deploying in three large units that advanced in crescent formation toward an encampment of Asian forces to the south of Megiddo. The inscription at Karnak records that: “The southern wing of his Majesty’s army was at a hill south of the Qina [brook], and the northern wing to the northwest of Megiddo, while his Majesty was in their center, [Amun] protecting his person (in) the tumult, and the strength of [Seth pervading] his limbs.”

That maneuver sparked panic among the enemy warriors; many of them abandoned their tents and rushed toward Megiddo. The pharaoh’s troops set about plundering their camp, which allowed many of the Asian forces to escape.

A NARROW PASSThutmose III leads his troops toward Megiddo through the perilous Aruna pass. Choosing this route was a bold initiative that allowed the pharaoh to surprise the enemy.

BRIDGEMAN/ACI

Some Asian commanders were hoisted to safety over the walls of Megiddo by those inside who were defending the city. Others must have run northward to get as far away from the Egyptian troops as possible. The chronicles point out with a certain bitterness that if the soldiers of Thutmose III had pursued the fleeing troops in that phase of the confrontation, the victory would have been quick and definitive: “When they [the enemy chiefs] saw his Majesty overwhelming them, they fled headlong [to] Megiddo with terrified faces, abandoning their horses, their chariots of gold and silver, so as to be hoisted up into the town by pulling at their garments. For the people had shut the town behind them, and they now [lowered] garments to hoist them up into the town. Now if his Majesty’s troops had not set their hearts to plundering the possessions of the enemies, they would have [captured] Megiddo at this moment.” This portion was less of a battle and more like a series of skirmishes with the Egyptians on the offensive.

MISSION MEGIDDOLocated on a hill in the north of present-day Israel, Megiddo controlled the important trade route linking Egypt with Mesopotamia in the mid-15th century B.C.

ALAMY/CORDON PRESS

Siege and victory

Faced with the impossibility of taking the city by assault, the Egyptians decided to besiege it, building a series of fortifications with wood they obtained by felling trees in the surrounding area. The Annals of Thutmose III show how he emphasized the strategic importance of conquering Megiddo: “Every prince of every [northern] land is shut up within it, the capture of Megiddo is the capture of a thousand cities!”

Finally, after seven months of siege, the city surrendered. Among the enemy leaders captured inside was the ruler of Megiddo. The prince of Kadesh, commander in chief of the Asian coalition, did, however, manage to escape.

An extraordinary booty

The written sources preserve a long and detailed list of the booty obtained after the conquest of Megiddo. They indicate that there were 83 enemy dead and 340 prisoners, but these figures may only include individuals who were seen as significant.

Apart from herds, provisions, and other objects, the Egyptian army took 2,041 horses; 924 chariots, among which were the chariots carved in gold belonging to the rulers of Kadesh and Megiddo; 200 sets of armor; and 502 composite bows. These bows, of Mesopotamian origin, were very expensive and highly sought after. The body armor, made of hardened leather or bronze mail, was innovative at that time. There is no mention of helmets, although their use was widespread during the rule of Thutmose III. This is demonstrated both by the lists of tributes from Asia and by the paintings in some private Theban tombs in which foreigners paying tribute are shown wearing helmets.

(Nubian kings ruled Egypt for less than 100 years. Their influence lasted centuries.)

A hunting scene depicting a charioteer graces a gold platter from Syria from around the time that Thutmose III dominated the region. Louvre Museum, Paris.

SCALA, FLORENCE

Myth and might

The immediate consequence of the victory was the consolidation of pharaonic control over much of what is today Israel and the Palestinian territories. The stunning victory, and expansion of the pharaoh’s control, would live in the Egyptian imagination as the beginning of a new era of regional greatness.

You May Also Like

General Djehuty, appointed governor of the conquered areas by Thutmose, would later be immortalized as the hero in an ancient Egyptian tale, “The Taking of Joppa.” Recounting how Djehuty used his ingenuity to conquer the city of Joppa (modern-day Jaffa, near Tel Aviv, Israel) by smuggling soldiers into the city hidden in baskets, this story preceded the Trojan horse plot device used in Homer’s epic poem The Iliad by centuries. It is also a likely source for the Arabic folk tale “Ali Baba and the 40 Thieves,” in which the eponymous thieves attempt to smuggle themselves into a house in jars of lamp oil.

THUTMOSE THE CONQUERORThis relief at the seventh pylon Karnak Temple Complex symbolizes the victories of Thutmose III over his enemies, who cower as he prepares to crush them with his mace.

ALAMY/CORDON PRESS

Beyond inspiring great stories, the Megiddo triumph forged new political and diplomatic realities across the region: The new Canaanite territory provided a closer starting point for Egypt to launch future campaigns into Mesopotamia. News of the impressive victory prompted monarchies in the Near East to send ambassadors to Thebes, capital of Egypt, with sumptuous gifts, hoping to curry favor with the pharaoh.

(These crocodile mummies are unraveling a mystery)

Following his victory, Thutmose III leveraged his position to expand Egypt’s power in Asia through an ambitious program of conquests in Syria. The Annals inscribed on the walls of the Temple of Amun-Re at Karnak mention 16 other campaigns, although, in some cases, no details have been preserved. These military operations took place between 1454 and 1437 B.C. and can be divided into distinct phases. The first phase involved the conquest of important port cities, such as Ullaza and Simyra, to facilitate transport to and from Egypt and provide storage points. The second phase involved the occupation of much of central Syria, thereby neutralizing the strength of the city of Kadesh. The third phase consisted of a direct attack on Mitannian territories, while the fourth phase included a series of campaigns aimed at suppressing uprisings in certain conquered territories.

Even accounting for Thutmose’s campaign of self-mythologization, and the inevitable exaggeration that is built into the claims and boasts of the Annals of Thutmose III, many scholars view the details of this account as a reliable source. In fact, the Battle of Megiddo is one of the earliest well-documented battles of history. This major turning point not only expanded Egyptian territory but also marked the first solo success of one of the greatest military leaders in ancient Egypt.

This story appeared in the May/June 2025 issue of National Geographic History magazine.