Now Reading: Unveiling Myths: The Truth Behind History’s Deadliest Shark Attack

-

01

Unveiling Myths: The Truth Behind History’s Deadliest Shark Attack

Unveiling Myths: The Truth Behind History’s Deadliest Shark Attack

Rapid Summary

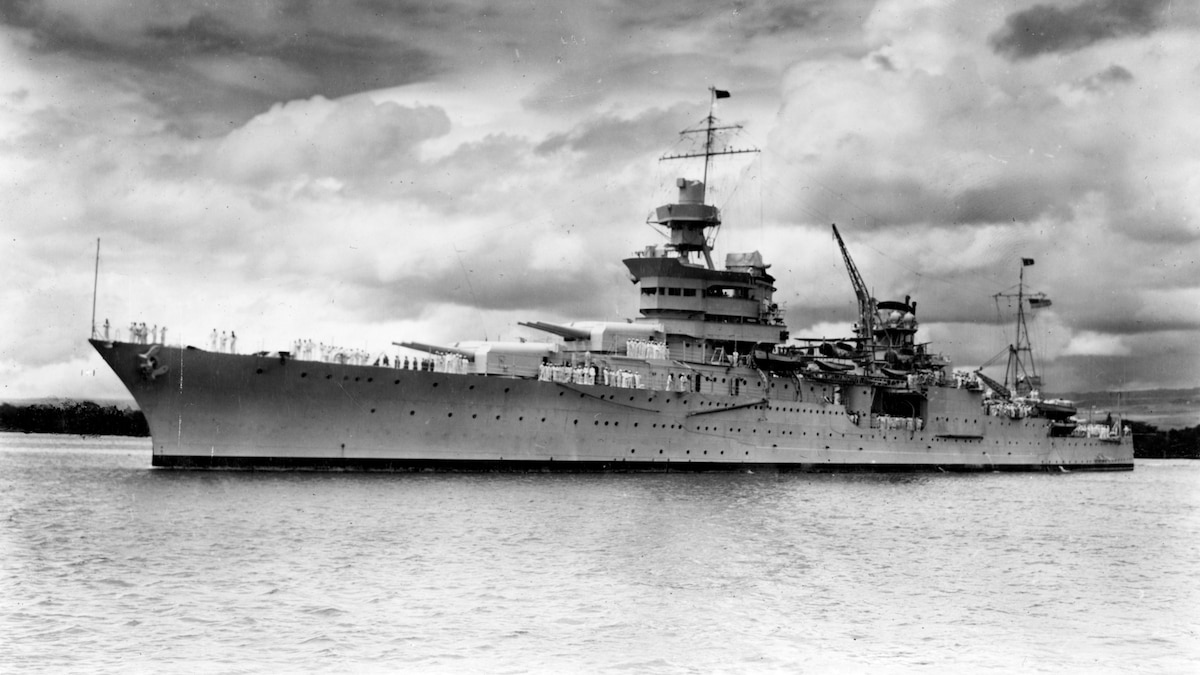

- The U.S.S. Indianapolis was a renowned WWII-era ship with 10 battle stars and served President franklin D. Roosevelt.

- In July 1945, the ship delivered components of the atomic bomb used on Hiroshima in a top-secret mission but sank after being torpedoed by a Japanese submarine shortly afterward.

- The sinking took just 12 minutes, leaving around 900 survivors in the water out of the initial crew of 1,195.

- Survivors faced horrors for five days, including dehydration, hypothermia, mass hallucinations from drinking seawater, and attacks by sharks. Of these attacks-primarily by oceanic whitetips-the worst shark attack in recorded history occurred during this disaster.

- Only 316 men were rescued on August 3 after Lt. Wilbur Gwinn’s chance finding during an air patrol led to rescue operations. poor processing of distress signals delayed aid efforts.

- Captain Charles McVay was controversially court-martialed for negligence post-sinking but exonerated decades later in 1996; he tragically committed suicide in 1968 before his pardon could be issued.

Indian Opinion Analysis

The U.S.S. Indianapolis incident remains one of history’s starkest examples of human endurance and sacrifice intertwined with bureaucratic failures during wartime operations. While the focus frequently enough lies on its infamy surrounding shark activity-highlighted by popular culture through films like Jaws, survivor testimonies reveal that thirst-induced madness and systemic lapses contributed equally to its numbing tragedy.

From an Indian perspective connecting global history narratives: This episode underscores war’s unpredictable tolls-not only those directly engaged militarily but also individuals performing ordinary yet critical duties under extreme secrecy or circumstance beyond their knowledge or control (akin elsewhere globally ). Secondly Its remembering via movies /media-stick-on legacy Actualizing care learned!=-Yet verifying that surviving relatives’ continually commit bridge-= .Instituted not stand-alone..https://www.nationalgeographic.com/history/article/uss-indianapolis-sh✈