Now Reading: How snowboarder Jeremy Jones is fighting to keep our winters cold

-

01

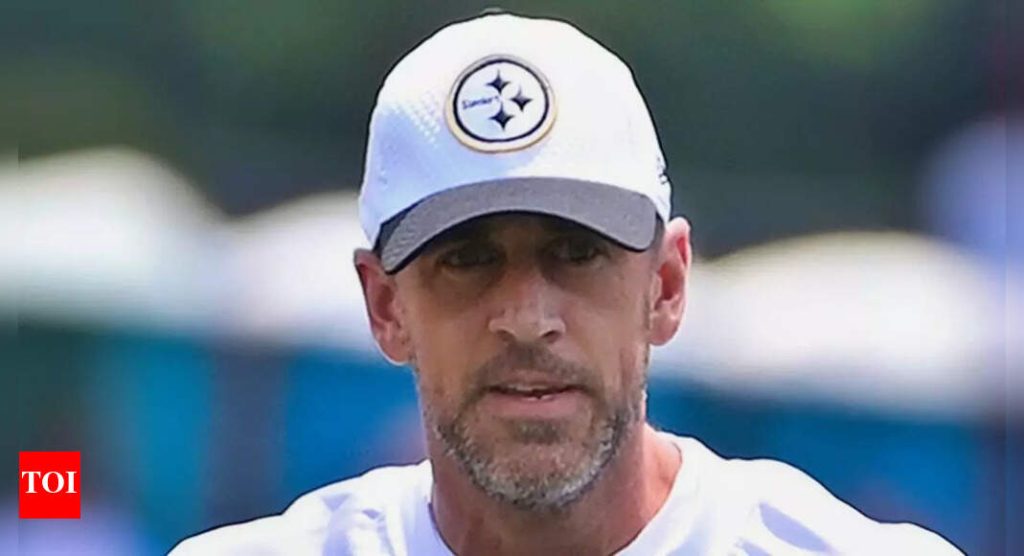

How snowboarder Jeremy Jones is fighting to keep our winters cold

How snowboarder Jeremy Jones is fighting to keep our winters cold

A pioneer of big-mountain snowboarding, Jeremy Jones watched as helicopters made remote backcountry runs suddenly reachable, enabling access to lines that had once been unfathomably remote. “We would get dropped in the mountains and link up these runs where you hike and ride and hike and ride,” he says. “I was like, Oh my God, this is where I need to be.” But he had misgivings about the means of ascent. “I knew, when I got in a helicopter, I was taking up resources,” he says. He began hiking up mountains instead and found the experience exhilarating. “The snowboard is a tool to challenge yourself to connect with nature. When you strip away the machines, the tool is much more effective.”

Jones became a splitboarder, ascending slopes on skis that could be combined into a snowboard for the ride back down, and eventually created his own company to manufacture equipment for the pursuit. He resolved to use the cleanest available materials and to give one percent of sales to environmental organizations, but he couldn’t find any nonprofits in the snow sports world focused on climate change solutions. So, in 2007, he launched his own: Protect Our Winters, aptly known as POW, a nod to fresh powder.

The group’s alliance of elite athletes now includes Jessie Diggins, the gold-medal-winning cross-country skier; Jim Morrison, a world-class ski-mountaineer; and Tommy Caldwell, one of the greatest rock climbers on the planet. Together they represent the interests of what POW calls the Outdoor State, the millions of Americans who consider the outdoors a central part of their lives. It’s a diverse group—about 31 percent Republican, 40 percent Democrat, and 29 percent independent, according to a 2019 market research study commissioned by POW—and Jones is fond of saying that the mountains aren’t blue or red but purple. Among POW’s trickiest challenges is convincing conservatives that climate change legislation will help save the ski resorts and snow sports they love. “Certainly, we’re going to find people that fight against us,” Morrison says. But, he explains, “we want to get outside the tribe and make a difference.”

The group runs campaigns to protect public lands and “Stoke the Vote” drives, in which movies and free-flowing beer are followed by panel discussions with climate scientists. But POW flexes its true muscle on lobbying trips to Washington, D.C. “POW’s magic is, we roll into Capitol Hill, we have gold medals with us, we’ve got Tommy Caldwell with us,” Jones says. “The aides are like, ‘There’s 30 million Instagram followers sitting in your office. You should probably go talk to ’em.’”

Jones likes to think the group might have played a small role in the passage of the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022, which relied on critical support from West Virginia senator Joe Manchin. Partnering with Snowshoe, the largest ski resort in the state, POW stressed to Manchin how many jobs on the mountain could be saved by the bill. “Shortly thereafter, he took that key vote,” Jones says. “And who knows how much that played a role?” Erin Sprague, POW’s chief executive, stresses how the group’s athletes can make climate change feel less like a political issue and more like a human one. “You have these inspirational humans who do so much for our country and communities, who have become experts in climate and trusted messengers,” she says. “They don’t have a political agenda. They’re there representing the places that they’re from, and their beliefs.”

POW is hoping to reverse a bleak trend at U.S. ski resorts: A recent study found that climate change has made the season roughly a week shorter than it was 50 years ago. “If the resorts’ chairlifts aren’t spinning, then people aren’t getting their coffee, they’re not renting their houses, they’re not going out to dinner,” Jones says. “When you come on a rainy January weekend, it’s so drastic. The difference between an average winter and a nonwinter is catastrophic.”

With resort season receding, backcountry trails are more crowded than ever, Jones says. There’s also more complex snowpack in the mountains, which can make avalanches a greater risk. So Jones is proceeding with a bit more caution these days. “When it comes to proper backcountry lines and really getting after it, I have this motto: ‘If it’s not a screaming yes, it’s a no,’” he says. “And I think I have more patience with the mountains. But I am still out there.” So is an army of snowboarders and skiers, all hoping that next winter they’ll get in a few more runs.

A version of this story appears in the April 2025 issue of National Geographic magazine.