Now Reading: A Truer Story of Native America

-

01

A Truer Story of Native America

A Truer Story of Native America

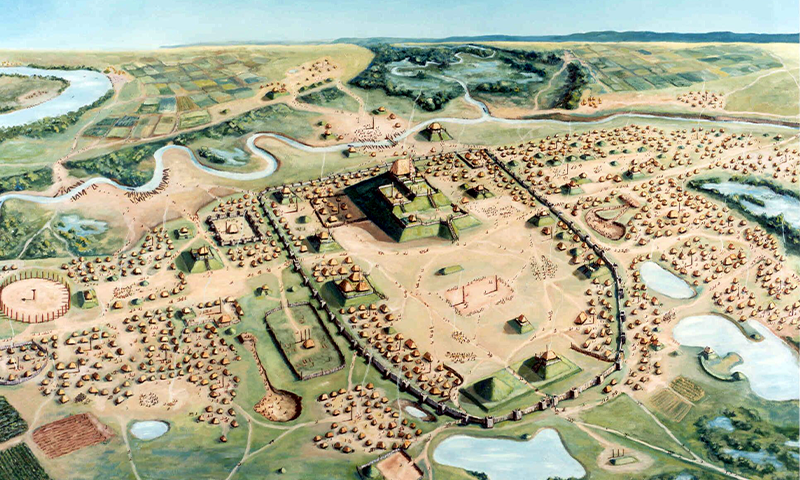

A brilliant supernova visible across North America and much of the rest of the world in the 11th century is said to have inspired an explosion of civilization building among Indigenous cultures across the Mississippi Valley and the American Southeast. One of the grandest cities was named Cahokia, which sprung up near what is now St. Louis. Cahokia had a plaza the size of 30 football fields and earthen pyramids up to 100 feet tall and it quickly swelled to become the largest pre-Columbian settlement north of Mexico: The city’s peak population of more than 10,000 rivaled London’s at the time. But it was just one of many Native American metropolises. The Huhugam people’s sprawling civilization in the Southwest, for example, contained more than 1,000 miles of canals.

These cities were abandoned by the late 14th century amid climate change and political instability, an exodus that many European settlers perceived as signs of the civilizations’ decline, according to written accounts. But in reality, many of the Indigenous peoples’ left their cities in a purposeful way, to create more egalitarian and sustainable societies, according to recent scholarship from historian and author Kathleen DuVal. And these Native societies continued to make up the majority of the North American population through the mid 1700s and to control most of the land and resources on the continent for a century after that, says DuVal. Her findings contradict myths perpetuated by white settlers and historians for centuries—namely, that Native influence had greatly declined by the 19th century, and that Native populations lacked advanced civilizations.

DuVal outlines these arguments in her 2024 book, Native Nations: A Millennium in North America, which recently won a Pulitzer prize. A professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, DuVal specializes in early American history and her work aims to amplify the voices that are often overlooked in historical accounts, including enslaved and Indigenous people, and to connect their narratives with the present. When preparing Native Nations, DuVal took care to work closely with Native American historians and scholars to ensure fidelity to their own accounts of their history. Many other historians of North America’s colonial period have relied primarily on texts and sources from white colonial settlers, though this emphasis is shifting.

Nautilus spoke with DuVal about how her work rewrites the history of North America, her efforts to foreground Native scholarship and what lessons the story of Indigenous retreat from cosmopolitan cities has for today.

Your book is described as reshaping the history of the North American continent. How does it do that?

This book takes a long view. It’s 1,000 years of history, and that puts the United States in context—the U.S. has been here for just about 250 years. Native nations have been here for millennia, and they’re still here today within the United States, Canada, and Mexico. That longer timespan helps us both to realize that the United States and the things the country has done were not inevitable, and that they are only a small part of Native American history.

You note that most of North America remained under Native control into the 19th century. Why has this history gotten lost in modern retellings?

There was an intentional forgetting in the late 19th century and early 20th century, when white Americans told themselves that this continent really didn’t belong to Native Americans, that there weren’t that many of them and they weren’t that organized. I think that was part of coming to grips with the fact that the United States did some really terrible things—forced people off of their land and fought some brutal wars against Native Americans. It was easier to believe that Native Americans had never really been important for white Americans to ease their consciences.

What might what is now the United States look like if, as you wrote, “British colonists could have lived side-by-side with Native nations, continuing to ally and trade in mutually beneficial ways?”

It would have looked more like what people imagined before the 19th century. It wouldn’t just be one country—it would be multiple countries. There would be Native nations with their own territory and sovereignty, completely separate from but maybe allied with other Native nations. Maybe some countries that were multiple Native nations coming together, but it wouldn’t be all one country.

There was an intentional forgetting in the late 19th century and early 20th century.

This book traces the embrace and then rejection of urban life by Native American groups and their transition to less centralized communities. Can we take lessons from these decisions today, particularly given your observations of these Native societies’ climate-driven struggles with agriculture and the hoarding of wealth by Native elites?

It tells us there’s a different way to organize societies. These societies were more democratic and egalitarian than Western European societies at the time, or than the United States that was created. There are different kinds of ways to live on the land and in a community. These nations were smaller-scale than the United States, but I think at least locally, on a county and state level, there are ways we can now imagine having values that mirror that focus on reciprocity.

You have long worked to highlight marginalized voices in early America and offer a perspective outside of the colonial outlook. Is it challenging to find primary sources?

It is less difficult than I thought it would be to find many different kinds of voices from the past. Looking at the 17th and 18th centuries, almost everybody who was writing things down were white men. But those white men also recorded what Indigenous people said to them. It’s clear from those records that the white writers knew that these Indigenous people mattered and had power, even when the writers didn’t like the things they were trying to do. For example, in the 17th and 18th centuries, French and Spanish officials who were sent out to Quapaw country, in what’s now Arkansas, wrote back reports to their superiors in Paris and Spain. They wrote down long speeches that Quapaw chiefs gave to them and described what was going on with the Quapaws and the people they were fighting against. These records aren’t perfect: They don’t come directly from Quapaws, but tell us a huge amount about what they were doing and what mattered to them at the time.

You made a special effort to foreground Native perspectives and scholarships in this book. What do these perspectives bring to the work that you could not provide yourself as a non-Native researcher?

There are almost 600 federally recognized tribes in the United States, and many more state-recognized tribes. I couldn’t possibly be an expert in the histories of all of them—much less what’s happening in the present day. One of the things this book tries to do is to connect the present with the past, so it’s been important to talk to scholars within tribes today who are doing things like working on language and reviving various parts of material culture, who have kept their own histories. For example, the linguistic work the Quapaw are doing within the tribe really has informed how I understand some of the Quapaw words and names that I’ve come across in old documents. That has enriched my understanding, and then I can tell readers about how the Quapaw people have seen the world through time.

You describe the history of Native North America as “a combination of victimhood and survival.” Would you say that this is a nuance that is often overlooked in the historical research on Native Americans and if so why?

The old story was basically that Native Americans either weren’t that important or were savage and obstacles to American progress. Then in the 1960s, there was a new story that corrected that, but it over-emphasized Native American victimhood. Now, that isn’t to say that Native Americans haven’t been victims to lots of terrible things, but that’s not the only story. In both versions, Native Americans don’t have much agency or individuality. What I hope this book does is show Native American history in a much fuller sense—even though, yes, terrible things have happened to Native Americans, they also have done all kinds of important things. They have a long, complicated history, not all of which has to do with other kinds of people. ![]()

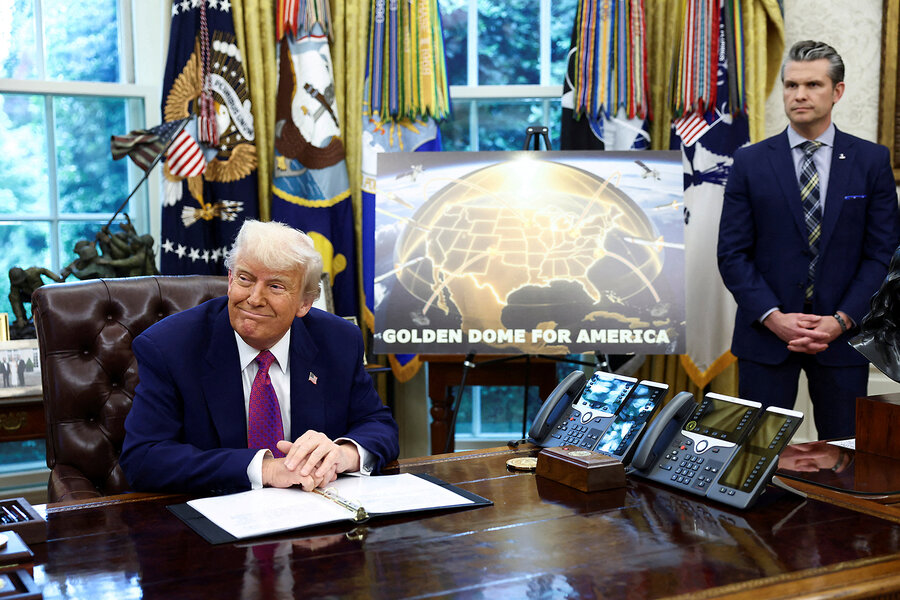

Lead illustration: Painting of Cahokia by William Iseminger, courtesy of Cahokia Mounds State Historic Site.

-

Molly Glick

Posted on

Molly Glick is the newsletter editor of Nautilus.