Now Reading: Ambitious book on quantum physics still fails to be accessible

-

01

Ambitious book on quantum physics still fails to be accessible

Ambitious book on quantum physics still fails to be accessible

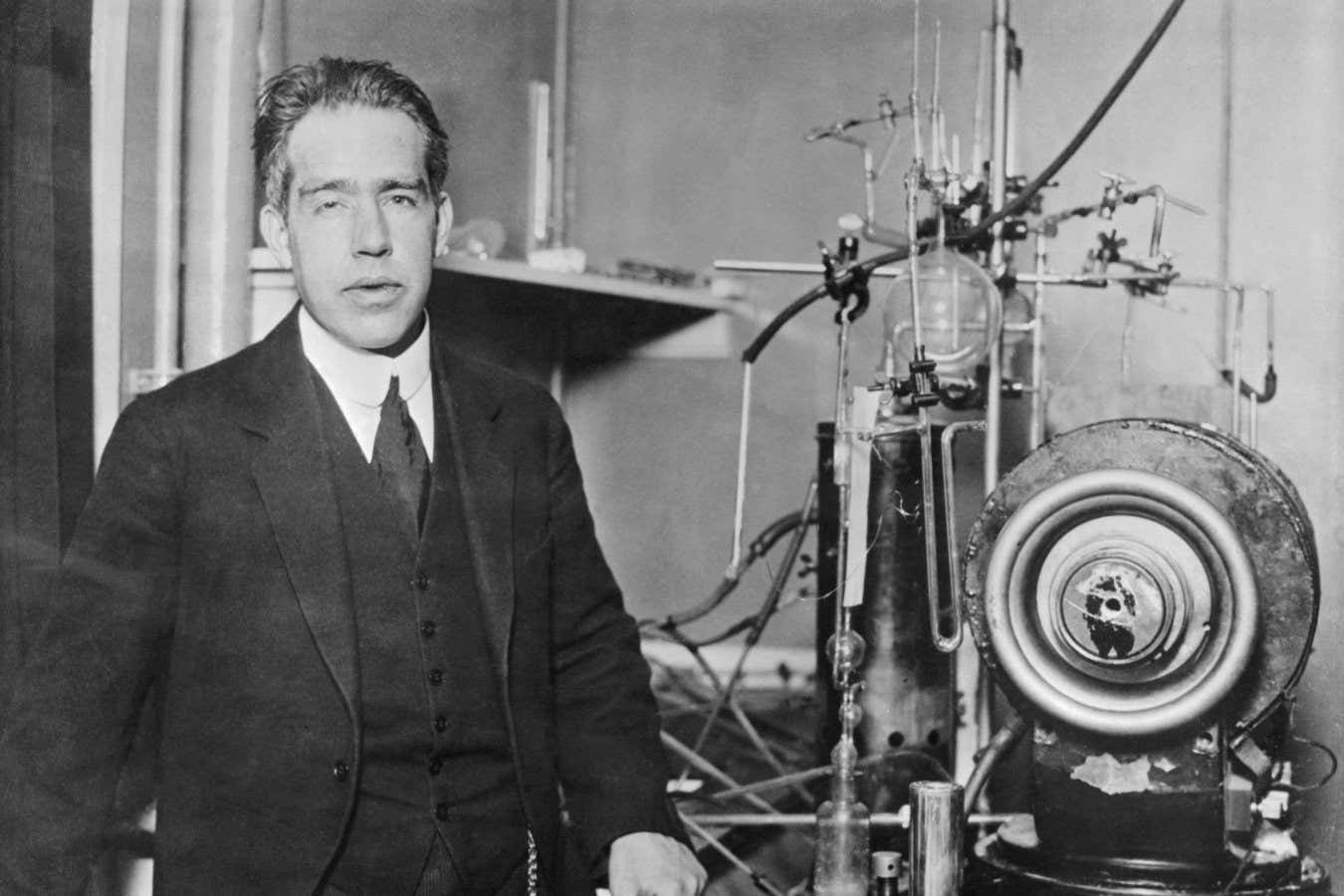

Niels Bohr in his lab at the University of Copenhagen

Bettmann Archive/Getty Images

Why Nobody Understands Quantum Physics

Frank Verstraete and Céline Broeckaert (Macmillan (UK, on sale; US, 10 February 2026))

Quantum physics isn’t just complicated – after 100 years, there is an awful lot of it to understand. This makes writing an accessible yet comprehensive book about the topic a challenge in both explaining it well and finding space to describe all the parts of our world it has touched.

Frank Verstraete and Céline Broeckaert’s Why Nobody Understands Quantum Physics (And Everyone Needs to Know Something About It) is an ambitious attempt, but the resulting 300-plus pages aren’t always completely successful.

They are a married couple – she is a language scholar and a writer and he is a physics professor – who wanted to combine their academic skills to write a book that would “inspire readers to see and feel new things, and to view the world from a fresh, quantum-inspired perspective”. In the preface, Broeckaert recalls struggling with mathematics in school, inviting the reader to engage with the text even if they had similar difficulties. “Quantum physics is an undeniable part of our culture,” she writes, while her husband notes that it is also “far from incomprehensible”.

What follows is a fast run-through of centuries of mathematics, physics and chemistry, starting in the 16th century when the foundations of empirical science were laid and ending with the present day. Their book truly has everything, from classical mechanics and the mathematics of matrices to lasers and the chemistry of combustion. Where many texts focus on one facet of quantum physics or choose to stop fairly early in its history, Why Nobody Understands Quantum Physics boldly moves forwards and gets to the edge of what researchers understand about quantum physics right now.

While reading, I excitedly jotted down numerous topics that I had only encountered while I was working on my PhD, yet here they were in a book for a general audience. It was wonderful to see something as technical and modern as the Hartree-Fock method or renormalization theory outside a textbook. The book ends with a brief discussion of quantum computing and quantum gravity, two truly contemporary topics that show up in my work as a reporter on the quantum beat nearly every day.

Yet even with my background as a physicist and a physics writer, I found some sections of Why Nobody Understands Quantum Physics more difficult to follow than the opening promised. Its chapters come in many brief sections, a rushed staccato of ideas and characters, densely filled with both jargon and tongue-in-cheek analogies or historical anecdotes.

Often, I felt the authors were choosing to be clever instead of taking the time to break down an idea and make it truly accessible. While I normally love a detour into history, by the end of the book I wished that more space had been made for old-fashioned physics writing.

Most disappointingly, Why Nobody Understands Quantum Physics didn’t seem to me a perfect fit for someone who is already intimidated by physics. Several sections of the book are designated as “for afficionados”, thereby drawing a stark line between different kinds of readers, while I was hoping that they would encourage everyone to take on the challenge instead.

I felt the authors were choosing to be clever instead of taking time to break down an idea and make it accessible

And bafflingly for a book that claims quantum physics can be understood by anyone, at one point the reader is directly told: “How does that work? Simple: by turning your intuition off and quantum logic on.” Do these choices not make quantum physics feel even more mysterious?

I found aspects of the language difficult, too. Many of the historical physicists are introduced in the hyperbolic language of genius, such as when Niels Bohr is referred to as the “lord and master of quantum physics”. And some linguistic flourishes also struck me as poor taste, such as referring to quantum physics having an “autistic side” and comparing equations based on which is “sexier”.

The fact that this bothered me as a reader might be a matter of personal sensitivity, but it also gave me pause as a writer myself. If I used similar language in my work, I would worry about alienating some of the readers that I think Verstraete, Broeckaert and I want to reach.

Before I became a physics reporter, I taught physics, and I was often asked about quantum physics. If I recommended popular writing to a student, I worried about two things: would the physics be explained well, and what would the student infer about physicists and the culture of being a physicist. Had a student brought me this book, I wouldn’t have discouraged them from reading it because it contains so much physics, but I would have definitely asked them for a debrief in office hours afterwards.

New Scientist book club

Love reading? Come and join our friendly group of fellow book lovers. Every six weeks, we delve into an exciting new title, with members given free access to extracts from our books, articles from our authors and video interviews.

Topics: