Now Reading: Are statins bad for you? Inside the debate on this cholesterol drug

-

01

Are statins bad for you? Inside the debate on this cholesterol drug

Are statins bad for you? Inside the debate on this cholesterol drug

Inside the average doctor’s office, statins aren’t controversial; they’re a crucial lifesaving tool used to lower dangerously high cholesterol levels, reducing risk of heart attack. But on social media, the drug is often villainized, painted as a poison pill, or a symptom of a diseased medical system. Recently, influencers have claimed that statins cause more harm than good and have endless side effects. Others take even bigger swings, claiming that the fundamental science behind cholesterol is a myth, one that’s used simply to sell more statins.

“If you only went online,” Spencer Nadolsky says, “you would never want to have a statin.” Nadolsky, a physician who specializes in obesity and lipids, is familiar with the social media critiques.

“It’s one of the most fear-mongered yet amazing drugs of our time,” he says.

How did boring generic pharmaceutical—a drug prescribed to 200 million people worldwide—become controversial? Part of the answer is influencers who proselytize ketogenic and carnivore diets, promising weight loss and other health benefits through the consumption of high fat consumption and limited carbohydrates. When adhering to one of these diets, the body uses fat as its main fuel source instead of carbohydrates, which can lead to loss of body fat while maintaining muscle mass.

The success of these diets is often bolstered by fit social media influencers eating red meat off a cutting board, touting the benefits of their preferred version of a low-carbohydrate, high-fat diet. One influencer even claimed that her transition from a vegan diet to a carnivore diet cured her of everything from brain fog to flatulence. But keto and carnivore have been associated with dramatic increases in low density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol—the cholesterol most strongly associated with heart disease, often called the “bad” cholesterol. Rejecting the lipid hypothesis, many influencers cast doubt on the widely accepted concept that cholesterol contributes to atherosclerosis, which is the buildup of fats and cholesterol in and on the artery walls.

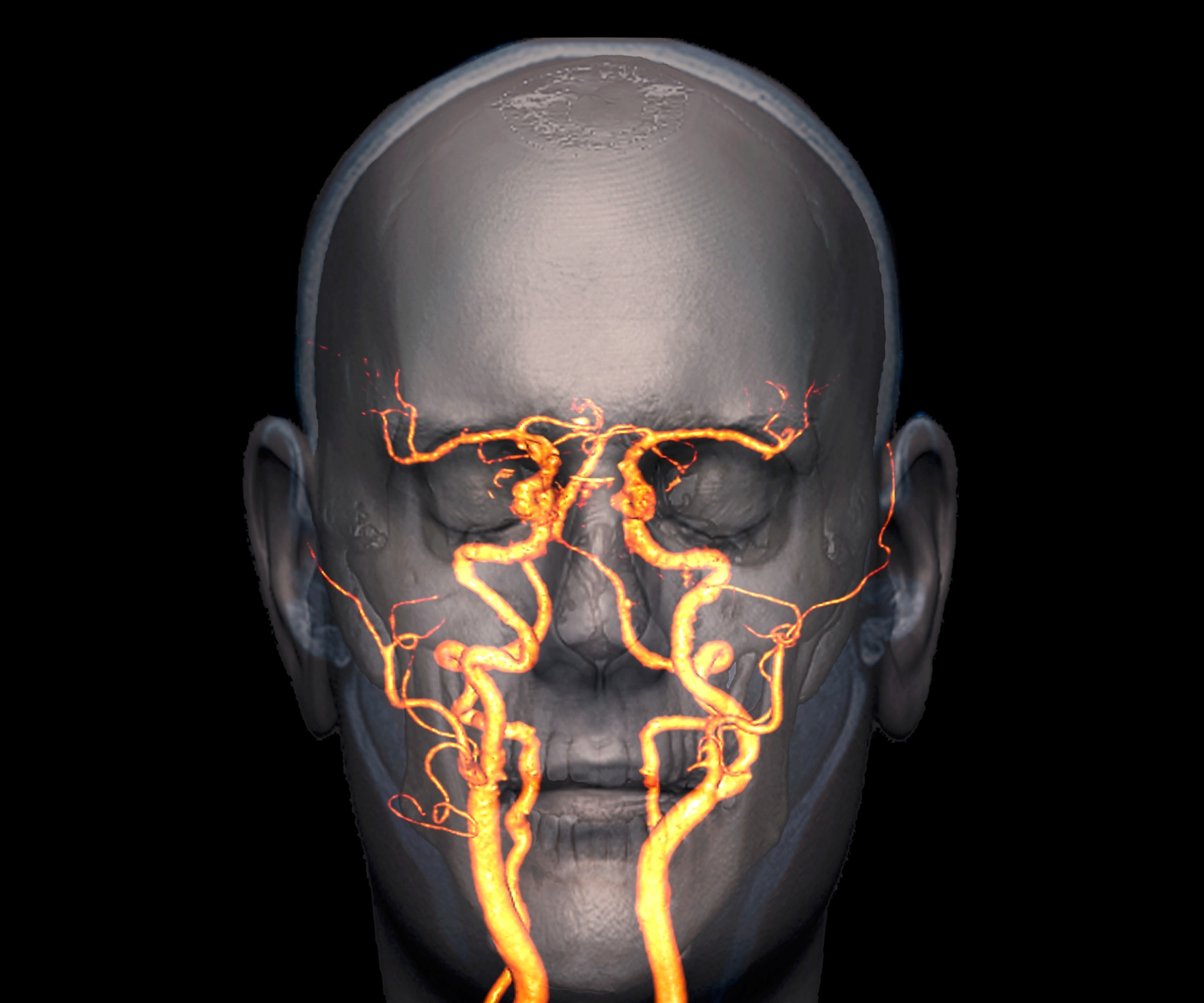

The head of a 60 year old patient with high blood pressure and high blood cholesterol. The blood vessels are the result of atherosclerosis which is the buildup of fats and cholesterol in and on the artery walls.

Image by Zephyr/Science Photo Library

Clinical lipidologist Tom Dayspring describes claims like these as “ketogenic nonsense.” He says that patients might not experience any symptoms of atherosclerosis until it’s too late. What some people don’t understand, Dayspring explains, is that heart disease only presents symptoms like chest pain and arrhythmia in very late stages of progression. Symptoms, Dayspring notes, can’t be used to diagnosis the disease.

“Most people are dropping dead before they get any symptoms of heart disease,” he says.

How smelling roses could help you make stronger memories

A scent, a touch, or a sip can be just what you need to lock an important moment into your mind forever.

Dayspring says that LDL levels in the United States follow a bell curve. In general, doctors want to get their patients to the 20th percentile or lower, or around 100 mg of LDL cholesterol per deciliter of blood. Once you go above the 20th percentile, the exponential risk becomes a “straight line to heaven,” Dayspring says. The only way to reduce serious medical issues like heart attacks, heart failure, and strokes brought on by plaque accumulation in the arteries is to achieve very low levels of LDL cholesterol.

Dayspring describes it as “an illegal dump job of cholesterol in your artery wall.” A lipid can only travel through plasma when it’s wrapped in a protein known as a lipoprotein. “Some lipoproteins, for whatever reason, leave plasma, crash the artery wall, and dump their cholesterol.”

That’s where statins can help.

Low-density lipoproteins, or LDLs, are molecules that are a combination of fat and protein and are the form in which lipids are transported in the blood. LDLs transport cholesterol from the liver to the tissues of the body, including the arteries, which has lead LDL being known as “bad” cholesterol.

Micrograph by Science Photo Library

A colored transmission electron micrograph of high density lipoprotein (HDL), or ‘good’ cholesterol. HDL cholesterol plays a role in fat metabolism and contributes to cardiovascular health

Micrograph by Lennart Nilsson, TT/Science Photo Library

How statins and other cholesterol-lowering drugs work

Approved in the United States in 1987, statins work by blocking an enzyme in the liver—where most of the body’s cholesterol is produced—which prevents LDL production. Statins reduce the risk of heart attack, stroke, and heart disease, which is still the leading cause of death in the United States. Over 40 million Americans currently take statins.

Until the early 2000s, statins were the only game in town for managing cholesterol, Dayspring says. Now, there are newer drugs that can also help. One class of drugs, PCSK9 inhibitors, lowers LDL cholesterol by blocking the protein that binds to LDL receptors, keeping these receptors available to clear LDL cholesterol from the blood stream. Unlike statins, these drugs haven’t been vilified by.

While LDL is often referred to as the “bad” cholesterol because it can contribute to plaques, and HDL is called the “good” cholesterol for clearing excess cholesterol from the arteries, it’s not black and white. The body requires LDL to function since it assists in cellular construction and repair and serves as a building block for many essential hormones. “I tell patients up front, [LDL] is the delivery cholesterol, because every tissue in your body needs tens of thousands of doses of cholesterol every day,” says Stephen Kopecky, a preventative cardiologist and the director of the Mayo Clinic’s Statin Intolerance Clinic in Minnesota.

“If you didn’t have it, you’d be dead,” Kopecky explains. “So it can’t be that bad. There’s a sweet spot.”

But LDL is just one measure of cholesterol. Dayspring thinks the most measurement to pay attention to is apolipoprotein B, or ApoB, the protein component found in several lipids, including LDL, but not HDL. ApoB, involved in cholesterol transport, is considered superior to LDL cholesterol to assess the risk of heart disease. Unlike LDL cholesterol, ApoB captures a more complete picture of all potentially plaque-causing particles in the blood. For example, a person with normal LDL cholesterol but high ApoB would still be at risk for heart disease.

Looking at ApoB is relatively new in the United States, which has historically used LDL. But the rest of the world uses this measurement, says Kopecky.

Statin side effects and intolerance

Like all medication, statins have side effects. On social media, these side effects are often front-and-center, used by influencers to show that the drug is inefficient or steer followers from considering the medication altogether. The most common are muscle aches, headaches, digestive issues. More seriously, for people with insulin resistance, there’s an increased risk to develop Type 2 diabetes (though the American Diabetes Association advises that people with diabetes go on a statin if they’re older than 40).

To Nadolsky, the benefits outweigh the risks. He compares taking statin to taking daily multivitamin.

You May Also Like

In his practice, he’s able to convince skeptical patients who’ve bought into the influencer-driven narrative around statins with some basic facts. If the patient claims that LDL cholesterol is not the cause of development of plaque in the arteries, he’ll point out that the association is “one of the most grounded scientific things we know.” Nadolsky’s claims are backed up by a trove of evidence, including a 2017 a meta-analysis in the European Heart Journal. That paper found that the totality of evidence “unequivocally establishes” that LDL causes atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ACSVD.) In 2020, the panel restated its conclusion, and also identified emerging evidence for ApoB’s role in ASCVD.

Some patients, however, are statin intolerant. A 2022 meta-analysis drawing on 4.1 million patients found statin intolerance within 9.1 percent of this population. By Kopecky’s estimation, there are three types of statin intolerant patients: those who experience body aches on the medication, and who cycle their use on and off to manage their cholesterol. Kopecky is part of this group. He experiences muscle aches after several months on a statin. Doctors will sometimes temporarily discontinue a patient’s statins and then add statins back to their regimen with either modified doses or a different statin to curb side effects.

A second group experiences “these weird symptoms that aren’t really related to when they take the medicine.” Researchers have observed a nocebo effect, or negative placebo effect associated with statins, and one 2020 study found this effect might be increasing.

The third group, which Kopecky finds most concerning, are those worried about potential statin intolerance, who won’t ever visit Kopecky’s office. Many patients, he says, will come in and say, “I don’t want to take this drug. I’ve been on the Internet. I know that’s bad for me, doctor.”

A statin’s effects on the brain are another concern around the medication. Statins are the only drug that can cross the blood-brain barrier and inhibit cholesterol synthesis in the brain, which is the body’s most cholesterol-rich organ, Dayspring explains. Cholesterol is required for the brain to operate, but excess cholesterol in the brain can cause neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer’s.

Dayspring points to the evidence which, he says, shows that “statins do not hurt the brain in any way, but they actually improve dementia a little bit.” For the exceedingly rare group of people who experience brain fog while on statins, he theorizes that they’ve over-suppressed the brain’s synthesis of cholesterol. But since the brain makes its own cholesterol, drugs that lower cholesterol levels in the liver do not affect the brain’s cholesterol levels.

Self-guided research on cholesterol and statins can lead to conflicting advice. A quick scan of the best-selling heart health books on Amazon shows titles like The Great Cholesterol Myth and The Cholesterol Hoax, and other offerings that advise readers to load up on red meat, Kopecky says. These books capitalize on a well-established formula. Diet books, Malcolm Gladwell wrote in the New Yorker more than two decades ago, are “selling something that people want to buy: the idea that they can eat whatever they want.”

Beyond misinformation, part of the mistrust around statins is that drug companies didn’t initially provide all the information about the drug’s side effects, leading doctors, including Kopecky, to pass on incomplete information to patients. It took 20 years before doctors realized that statins can cause a minor increase in blood glucose, which can lead to type 2 diabetes. The lagging response, Kopecky says, has led to some patients to distrust their doctors on this specific treatment.

Cholesterol deposits causing the narrowing of a blood vessel which raises blood pressure and puts strain on the heart. Atherosclerosis is the main cause of heart attacks.

Photograph by Lennart Nilsson, Boehringer Ingelheim/TT/Science Photo Library

Colored coronary angiogram of a 53 year old patient with severe narrowing of the circumflex coronary artery.

Photograph by Zephy/Science Photo Library

The reality of lowering cholesterol

Regardless of claims on the internet, the only lifestyle change that can help control LDL cholesterol is significantly reducing the consumption of saturated fats, Dayspring says. For people with cardiovascular risk that can’t be controlled by lifestyle factors, pharmacological intervention is the only option. And the first drug doctors reach for is statins.

Lifestyle, Kopecky says, is incredibly important. While a large portion a person’s cholesterol is genetic, any positive change is welcome, according to the data. “Nothing you do to improve your health is ever too little, and nothing you do to improve your health is ever too late in your life,” he says.

But he’s bearish on keto. “You just can’t eat a keto diet forever,” Kopecky says. There is a healthy version of the diet, he notes—one that relies on extra virgin olive oil, nuts, and avocado oils as the primary fat sources, with just one ounce of red meat per day—but that’s a far cry from the steak-loaded cutting boards influencers tout on social media.

The carnivore diet often conjures mental images of predators in the wild, consuming double-digit pounds of meat per day. There is even one strict regimen of red meat, salt, and water, is known as the “Lion Diet.” But despite the image of a diet bridging the gap to our animalistic nature, only humans have high cholesterol, Dayspring notes. “Things that eat meat all day long, have LDL cholesterols of 15 to 20.”

How doctors are educating patients

One criticism of statins is that they’re overprescribed. And a recent study published in JAMA Internal Medicine found that’s likely the case, but it didn’t question the benefits of statins or their necessity. According to the study, “50 million US adults aged 40 years and older meet criteria for elevated ASCVD risk,” for a statin prescription, even by the study’s revised numbers.

To convince wary patients, Nadolsky shares a personal datapoint: he’s on a statin. “I practice what I preach,” he says. Statins are one of the best medicines in use, according to Nadolsky. “It’s just a shame that people aren’t utilizing them, due to the fear mongering that is done online.” A 2019 study published in JAMA Cardiology showed less adherence to taking statin medication was associated with more incidences of death for patients with ASCVD.

Kopecky, too, is concerned with patients who explicitly say they don’t want to take statins after reading about them on the internet. In response, his clinic polled 1,200 of these patients to see what would tip the scales to change their minds about statins. The patients wanted to know three things: cholesterol is involved in heart disease, doctors have a way to lower risk of heart disease, and the treatment is safe.

As a result, Kopecky and the Mayo Clinic released a series of videos to address each of these three points. Still, medical misinformation still runs rampant on social media and even crops up next to reputable professionals on social media. When viewing a YouTube video of Kopecky discussing statin misinformation on Mayo Clinic Radio, two of the recommended videos in the sidebar were a video purporting to reveal the “big pharma” conspiracy behind statins and a second one claiming that LDL cholesterol is a myth.

“LDL is not a myth, and you have to look at the totality of evidence,” Kopecky says. He thinks anyone with high cholesterol should seek treatment for it but understands they might not want to: “You can’t make everybody drink the Kool-Aid.”