Now Reading: Hilma af Klint Celebrates the Supernatural in Nature

-

01

Hilma af Klint Celebrates the Supernatural in Nature

Hilma af Klint Celebrates the Supernatural in Nature

Sign up for the free Nautilus newsletter:

science and culture for people who love beautiful writing.

The full Nautilus archive

•

eBooks & Special Editions

•

Ad-free reading

- The full Nautilus archive

- eBooks & Special Editions

- Ad-free reading

In the spring of 1919, enigmatic Swedish artist Hilma af Klint began documenting the flora and fauna surrounding her home on the green island of Munsö, about 24 miles west of Stockholm. She breathed loving detail into illustrations of species such the dainty Nottingham Catchfly, the white wagtail bird, and the sorbet-hued European Columbine.

But these works, which were recently displayed in public for the first time, are no run-of-the-mill botanical illustrations: Af Klint imbues her watercolors with traces of the occult, decorating them with mysterious diagrams that are meant to investigate the species’ spirituality and probe the connective tissue linking humanity and greenery. By closely studying her environment, af Klint wrote that she encountered connections “between the plant world and the world of the soul.”

It’s no surprise that af Klint would add supernatural flair to these earthy images. She’s best known for some of the earliest abstract art in the Western world, incorporating mysticism into striking geometric forms that vaguely mimic nature. She drew inspiration from Theosophy, an occult movement that emerged in the 19th century and posits that the entire universe is intricately linked.

The artist’s love of nature budded while spending summers with her family at their manor on the island of Adelsö, where her father introduced her to local plant and animal species. After graduating from the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Stockholm, af Klint began working as a scientific illustrator. Until the 20th century, this offered one of the few career opportunities for female artists.

Af Klint had already created now-renowned abstract works, such as the spiral-filled Primordial Chaos, before returning to her botanical muses during the spring and summer of 1919 and 1920. In the resulting series, Nature Studies, her watercolor pieces combine intricate renderings of plants, insects, and birds with notes on these beings’ human-like characteristics. Take the small, daisy-like plant coltsfoot, which she noted “can build a small society in which individuals work together.” Af Klint envisioned arranging these works into a botanical atlas that included spiritual analysis, titled An Attempt to Explain What Stands Behind the Flowers.

“With its forms of branches and flowers, numbers of leaves, circulation, root fibers, cell structure, color, aroma, taste, and movement,” af Klint wrote, “the world of plants represents in matter what nature spirits have absorbed from the intellectual energies of the universe.”

While this atlas never came to fruition, the work was not wasted: Visitors can now explore af Klint’s Nature Studies at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City in an exhibit entitled Hilma af Klint: What Stands Behind the Flowers. Guests are invited to act as amateur botanists and inspect the watercolors with a magnifying glass, amplifying the mysterious diagrams of triangles and squares juxtaposed with plant and animal renderings. The works are neatly arranged throughout the exhibit, alongside dried plant specimens, which resembles an early 20th-century natural history museum yet presents an otherworldly twist.

This first public viewing of these paintings hews faithfully to af Klint’s well-known penchant for secrecy: She wanted her works to remain shrouded until after her death, so her paintings only began to reach the international stage in 1986—four decades after her passing.

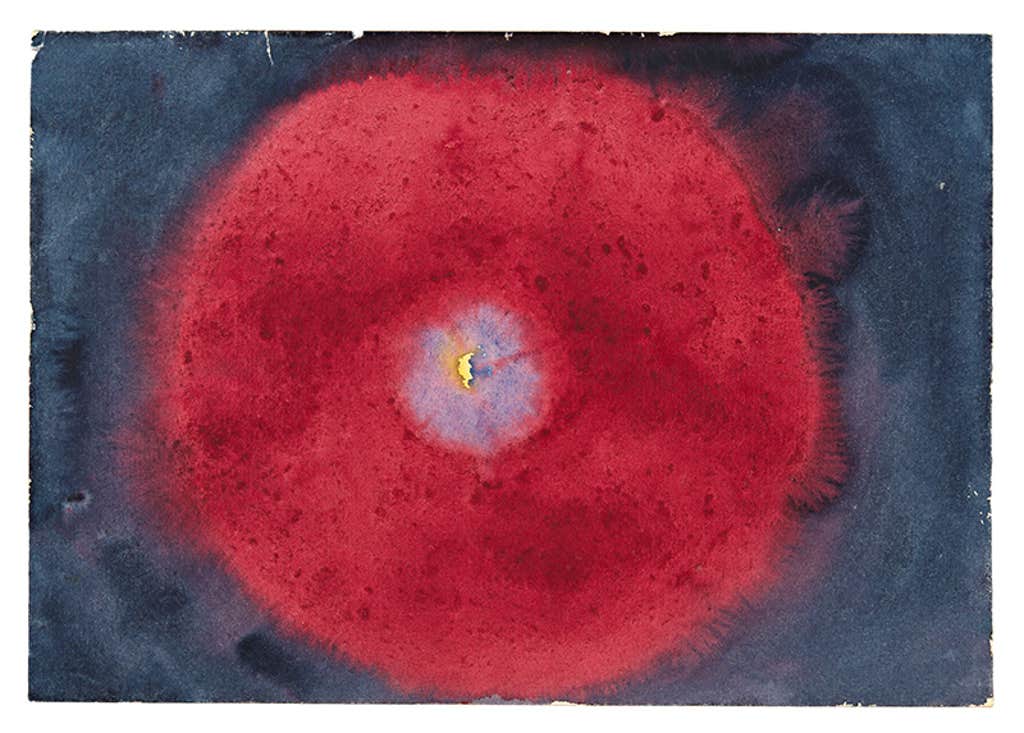

What Stands Behind Flowers also features af Klint’s quirkier approach to representing Swedish plants. Two years after finishing the paintings in Nature Studies, she completed On Viewing of Flowers and Trees. This series loosely portrays flora with blurry, wet-on-wet watercolors. Birch, for instance, features a dripping red splotch—reminiscent of the experience of staring at an object for so long that it becomes unfocused and alien. This technique was influenced by the theories of Austrian occultist Rudolf Steiner, who wrote that “colour is the soul of nature and of the whole Cosmos, and by experiencing the life of colour, we participate in this soul.” ![]()

Hilma af Klint: What Stands Behind the Flowers is on view until September 27 at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

Lead illustrations by Hilma af Klint

-

Molly Glick

Posted on

Molly Glick is the newsletter editor of Nautilus.