Now Reading: How the Trump administration is putting hundreds of sacred sites at risk

-

01

How the Trump administration is putting hundreds of sacred sites at risk

How the Trump administration is putting hundreds of sacred sites at risk

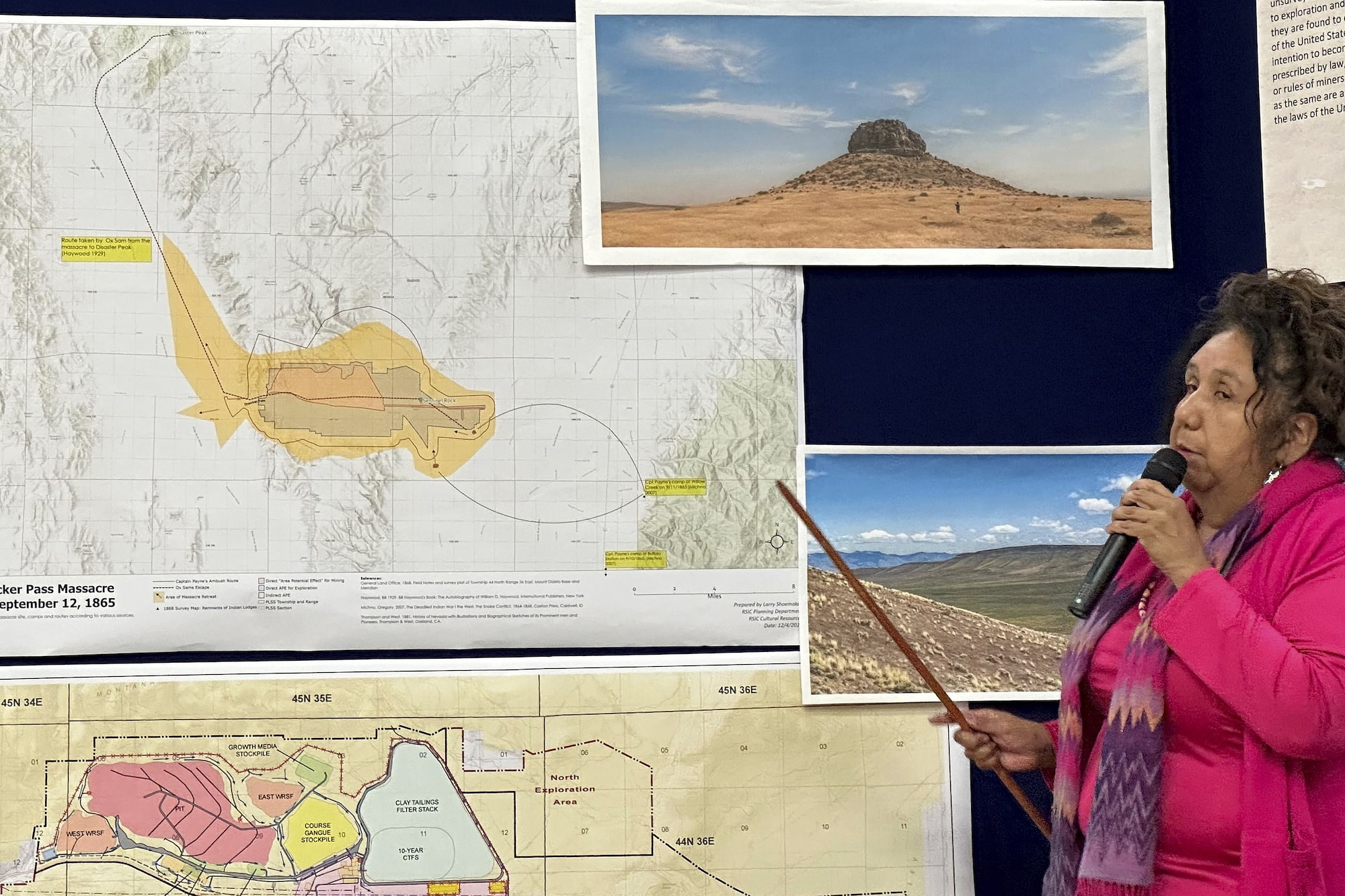

Any time a federal agency wants to develop a project in Wyoming — an oil and gas lease, a pipeline, a dam, a transmission line, a solar array — it has to go through Crystal C’Bearing first. C’Bearing is Northern Arapaho and the tribal historic preservation officer, or THPO, for the Northern Arapaho tribe, so if a new wind farm is proposed, for example, she determines if any tribal areas will be impacted by the project.

“It’s a challenging job, but I feel like it’s really important work,” C’Bearing said. “I feel a sense of gratitude that I’m able to do this and that I’m able to try, in my best ability, to preserve and protect what we have.”

C’Bearing’s scope extends beyond her home on the Wind River Reservation, to any and all lands ceded by treaty, routes tribal members took during the removal process, burial sites, and religious places. That means she reviews projects across 16 states in addition to Wyoming, from Wisconsin to Montana, New Mexico to Arkansas, and all points in between — traditional homelands of the Northern Arapaho and other Indigenous nations, acquired by the United States as it forcefully expanded westward. Because of that range, hundreds of federal proposals and reports flood her email inbox every week, as is the case with 227 other THPOs working for their respective nations. Many have overlapping historic homelands and histories.

Tribal historic preservation officers, like C’Bearing, are often a first line of defense against destructive federal projects, and rely on a range of skills from traditional ecological knowledge to a cultural and historic knowledge of places and landscapes. Now, their work is under threat.

declared a national energy emergency to speed the development of fossil fuel projects, mines, pipelines, and other energy-related infrastructure, cutting the amount of time federal agencies are required to notify Indigenous nations before starting a project. Now, as Trump’s proposed budget for 2026 works its way through Congress, the fund supporting the national THPO program is bracing for a 94 percent budget cut. On top of that, the Trump administration has yet to distribute THPO funds promised for 2025.

declared a national energy emergency to speed the development of fossil fuel projects, mines, pipelines, and other energy-related infrastructure, cutting the amount of time federal agencies are required to notify Indigenous nations before starting a project. Now, as Trump’s proposed budget for 2026 works its way through Congress, the fund supporting the national THPO program is bracing for a 94 percent budget cut. On top of that, the Trump administration has yet to distribute THPO funds promised for 2025.

Traditionally, THPOs like C’Bearing have 30 days to review a project: 30 days to review federal reports, conduct site visits, identify artifacts or burial grounds, and collaborate with tribal members, sometimes from other tribes. According to C’Bearing, that window was already tight, but under Trump’s energy emergency, that deadline is now seven days. And as the year rolls on, C’Bearing’s budget is evaporating. If the administration doesn’t release the THPO funds already promised, she’ll be out of a job come September.

“If this is the moment that breaks the system, there’s not going to be anything there to catch the THPOs,” said Valerie Grussing, executive director of the National Association of Tribal Historic Preservation Officers.

The THPO program was born out of requirements established by the 1966 National Historic Preservation Act — the legislation responsible for preserving and protecting historic and archaeological resources in the United States. At the time, public concern about historic places being altered or destroyed by federally-funded infrastructure as well as urban renewal projects prompted the federal government to take legislative action. The act mandates that all federal agencies identify any impacts their projects might have on areas important to states and tribes, and notify the public about those impacts. But Indigenous nations hold a particularly important role: Agencies must consult with tribes regardless of whether the project is located on, or off, federally recognized Indian reservations. That caveat fits within a broader context of treaty law and rights, as well as the federal government’s trust responsibilities requiring that agencies put “good-faith effort” into consultations.

If a THPO conducts their analysis and finds there’s no risk of a federal project impacting cultural or historic resources, the plan moves forward. If a THPO finds there is a risk, the tribe, federal agency, and state work out a formal agreement explaining how the impacts will be resolved or mitigated. That part of the process can take years.

Nati Harnik / AP Photo

With a significantly shorter review period, however, THPOs will have to make hard choices about the hundreds of reports that come in every week, the existing backlog, and prioritizing “emergency” projects at the cost of others. That means tribes won’t have a voice in how projects are determined on their homelands, putting countless cultural and historical sites at risk. Many of those sites are undeveloped wilderness areas, like with Pe’Sla in the Black Hills — a sacred ceremonial site for the Sioux, Lakota, and other nations — now facing exploratory drilling for graphite. Many of the world’s most resilient forests, like Pe’Sla, are protected by Indigenous peoples and provide climate change mitigation benefits by storing carbon.

“A lot of times we still have to take a deeper look and double check and triple check some of these areas and then coordinate across tribes if needed,” said Raphael Wahwassuck, THPO for the Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation. “It’s pretty unrealistic to have good work happen in that short of a window.”

As of April, 186 projects with an emergency designation have been cleared to begin construction. The designation includes controversial projects like Line 5 in Michigan, prompting seven Indigenous nations to walk away from federal negotiations. Fifteen states have sued the administration alleging there is no energy emergency and that the declaration illegally bypasses additional reviews of federal projects, like environmental impact or endangered species assessments.

“My worry is everybody is going to use the emergency declaration in one way or another on all of these projects and we’re just going to be bombarded with a ton of them,” C’Bearing said. “It’s just another added-on thing that we need to pay attention to, among the other hundreds of things that we do here.”

But beyond the truncated review timeline, funding is running out. Congressionally approved and appropriated funds for 2025 are still being held by the Office of Management and Budget, or OMB, awaiting additional review by the Trump administration. Neither the OMB nor the White House responded to requests for comments for this story. An official with the Department of Interior said that pending financial assistance obligations, including grants, are being reviewed for compliance with Trump’s recent executive orders.

“If this continues, oversight action should be taken—up to and including legal remedies to enforce the law. It’s not a suggestion. It’s not optional. The law requires these funds to be spent.,” Congresswoman Chellie Pingree, a Democratic representative from Maine, wrote in an email to Grist. She’s a member of the House Committee on Appropriations. “Holding up funding for tribal governments is wrong—morally and legally. Many tribes have been waiting for decades for basic investments in schools, housing, and infrastructure. And now, even when the funding has been approved by Congress, they’re being forced to wait again because of what appears to be a politically motivated delay that violates the law.”

Despite the outsized importance THPOs play for Indigenous nations, very few tribes can dedicate additional funds to maintain those roles. The majority rely entirely on federal funding, as the program was designed, Grussing said, and that allocation has only ever provided an average of one staff member per THPO office, per tribe.

“It’s been more difficult for tribes to prioritize historic preservation than usual. It’s usually pretty difficult, but now we’re seeing similar effects for tribal education, health, and housing,” Grussing said. Trump’s proposed 2026 budget cuts $911 million from the Bureau of Indian Affairs and the Bureau of Indian Education. “Expecting tribes to step up and prioritize historic preservation during this time is not realistic.”

With funding cuts across multiple points of tribal operations, tribes are having to make choices like funding their health and safety — or a THPO program. Wahwassuck’s concern is that if multiple tribes lose their THPOs and staff working on consultation requests, conditions will effectively go back to a pre-consultation period, as in the 1960s. In that world, tribal nations wouldn’t have opportunities to intervene or protect lands and cultural resources.

“There’s been a lot of profit made off of the blood and bones of our ancestors and off of the lands that our tribes have had to cede and be removed from,” Wahwassuck said. “I hear it mentioned pretty regularly that this administration wants to recognize tribal sovereignty and honor the trust and treaty responsibility. However, these funding actions directly go against those statements.”

Correction: This story originally misidentified the location of Line 5. It also gave the wrong affiliation for Raphael Wahwassuck.