Now Reading: Inside the foundry forging $15,000 katana swords

-

01

Inside the foundry forging $15,000 katana swords

Inside the foundry forging $15,000 katana swords

In a converted barn on a residential lane on Japan’s Tango Peninsula, some 75 miles north of Kyoto, three men are playing with fire. While robust flames lick the edges of a 2300-degree furnace, Kosuke Yamazoe uses a 15-pound hammer on a mass of white-hot steel, flattening it beat by beat in a hypnotic rhythm. Behind the shower of embers raining down on the earthen floor, Tomoyuki Miyagi grips the steel with a pair of iron tongs and bangs a smaller mallet in a melodic counterpoint. Nearby, at a small stove next to a soot-covered wall, Tomoki Kuromoto is making tea. This is the headquarters of Nippon Genshosha, one of the few remaining katana foundries in the world.

For hundreds of years, expert swordsmiths forged blades for Japan’s warriors, including the famed samurai. Early records show craftsmen’s names in the thousands, but a decline of the art began in 1876 with the outlaw of open carry. After World War II, the occupying forces in Japan then banned the production of katanas, resulting in additional lost works and livelihoods. Today it is believed there may be some 200 licensed makers left, not all active. Yamazoe, Miyagi, and Kuromoto are the only katana artisans in a region that’s home to one of the oldest blacksmithing workshops in all Japan. “There is a sadness that it’s dying out as a craft,” Kuromoto tells me through an interpreter. But together, they are honoring and elevating the vanishing art.

(Whatever happened to the samurai?)

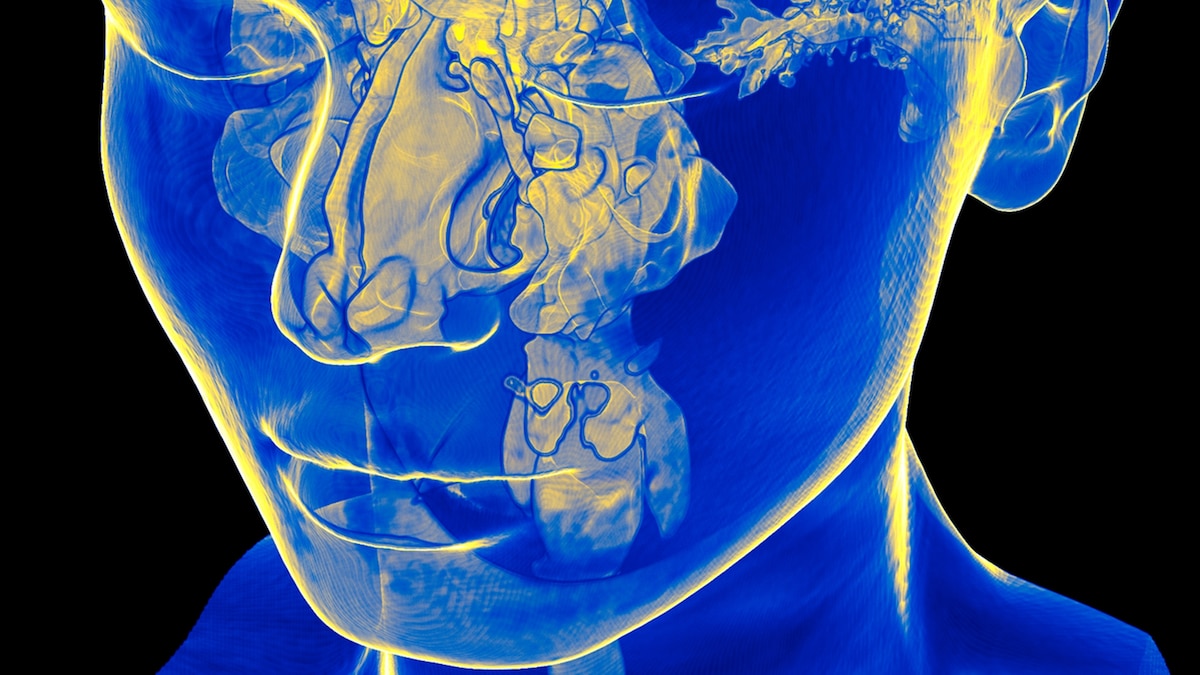

Kuromoto displays a tachi, a long sword once primarily used by warriors on horseback. Today’s blades are decorative and can be displayed in wooden scabbards or encased in resin.

The men, now in their 30s, met during a hard-sought 10-year apprenticeship in Tokyo with Yoshikazu Yoshihara and his father, Yoshindo Yoshihara, two of Japan’s most illustrious swordsmiths. (The elder Yoshihara’s work is in the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art’s collection; he himself was the grandson of a celebrity swordsmith of the Showa period, in the early 1900s.) After a brief stint working on their own, Yamazoe, Miyagi, and Kuromoto joined forces in 2019 and launched Nippon Genshosha from an abandoned barn owned by Yamazoe’s grandparents.

Swordmaking has long been an art form in Japan, and experts can date a blade much as a porcelain appraiser can date a vase or an arborist a tree. Nippon Genshosha swords are entirely hand-built, average around $15,000, and are sought after by collectors. As with most katanas, they’re made from tamahagane, a type of steel that comes from iron sand mined in the Shimane Prefecture, north of Hiroshima.

The five-figure price tag is a result of the laborious fabrication process, which can take a year or more. It begins with three days of round-the-clock smelting in the clay furnace. The technique of heating and methodical hammering helps draw out the slag—the waste product that results from smelting—and purify the steel, which is fused and folded into hundreds of fine layers. The hard steel is then worked into shape, and the razor edge of the blade is refined.

Much of a sword’s allure lies in the way the surface of the blade catches and throws the light. “Instead of reflecting a clear beam of light, one solid beam, it will be speckled or broken up,” says Kuromoto, twisting a newly buffed blade in the sunlight as it pours through a window.

But while they work to keep an age-old art form alive, the partners are fighting an uphill battle. Demand for high-dollar katanas is waning, and the success of Nippon Genshosha depends on finding and developing a new generation of collectors, not just appealing to existing ones. To that end, the men have begun taking liberties with the hamon, the pattern etched along the blade edge. Traditionally, a smith designs a unique hamon, often featuring landscape patterns tied to the area where the sword is manufactured. But, says Kuromoto, “if someone from the United States wants a scene from their front window, they can send a panoramic photo and we can reproduce it.”

They’ve also pioneered a method of encasing blades in a sealed, transparent-resin block rather than a traditional wooden sheath. “The idea,” says Kuromoto, “was that this would allow people to appreciate Japanese swords safely and thus focus more on their beauty. What is the point of art if you can’t see it?”

In a country reverential of long-held traditions, the swordsmiths are striking a delicate balance. “It seems that ordinary people have fewer opportunities to come into contact with Japanese art,” says Kuromoto. “But today, as an art piece, swords have a place in modern culture.”