Now Reading: Kids See a Lot More Misinformation Than We Think

-

01

Kids See a Lot More Misinformation Than We Think

Kids See a Lot More Misinformation Than We Think

Thanks to faulty artificial intelligence, deepfakes and plain bad actors, children encounter a lot on the Internet that isn’t true. Here’s how to help them spot it

By Evan Orticio edited by Megha Satyanarayana

Fertnig/Getty Images

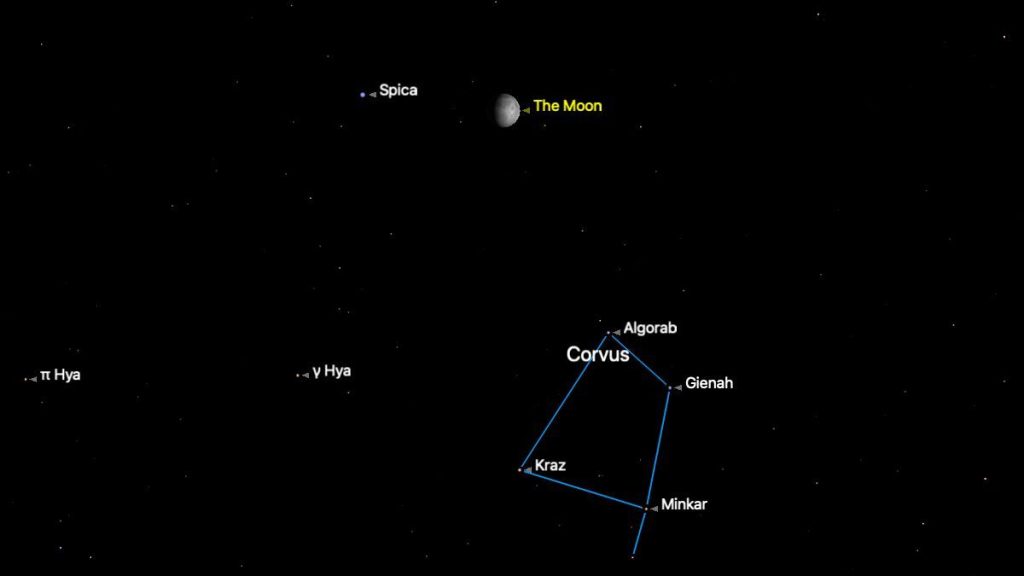

Aliens live on Neptune. Ancient pyramids generated electricity. Humans don’t cause climate change. You might imagine the typical believer of these claims to be a card-carrying conspiracy theorist, but they could just as easily be a curious nine-year-old with an iPad. YouTube reliably feeds AI-generated videos containing questionable claims like these to children, often in the guise of educational content. Children’s exposure to misleading information online isn’t new, but now AI has amplified the problem, allowing problematic content to be produced at a rate that moderators can’t keep up with. Even children who are online only in small doses likely see false or inaccurate information that might deceive them.

Engaging with AI directly can be just as precarious. AI tools, which in addition to ChatGPT include Microsoft Copilot and Google’s Gemini, regularly make mistakes and fabricate sources—a fact that the CEO of Google admits. By some estimates, over half of AI-driven answers have factual errors. Despite this, developers design AI chatbots to sound authoritative and confident, even when they aren’t. This is a perfect storm for misleading children, who may be particularly trusting of more natural-sounding, conversational content.

But, kids are already using these technologies, and they’re not slowing down. They are digital natives, and parents often misjudge how much time they spend on their devices, by more than one hour per day. Children are generally more familiar with new platforms like AI chatbots than are their parents, and may turn to these systems for things they’re afraid to ask their parents about. With Gemini becoming the first major AI platform to welcome children under 13 this month, these concerns are more pressing than ever. The bottom line is that kids are navigating the digital world, often on their own. Research that my colleagues and I have undertaken tells us that children need adults to be proactive in teaching them how to discriminate fact from fiction, even if their screen usage seems minimal and safe. Here’s how to start:

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Harness children’s natural curiosity and skepticism

Any parent knows the feeling of being caught in a never-ending loop of whys from their kid. When that curiosity strikes, join in. Provide informative answers, yes, but scaffold their thought processes too. “Great question, what do you think? What makes you think that? How would we find out what’s right?” You’ll foster intellectual humility and critical thinking by emphasizing the process of reasoning, not just the outcome.

Children are born skeptics, but they need help translating it in a digital setting. By around three or four years old, children can choose their sources wisely, and trust people who are accurate, confident and informed. Encouragingly, this discernment may translate to digital informants like computers too. Children even systematically investigate for themselves when they hear a surprising or counterintuitive claim. But judging online content can require fine-grained attention to details. Help bridge the gap by talking to elementary and middle schoolers about the cues they should look out for online, as when a story contains overly emotional language, sounds too good to be true or lacks specific, credible sources.

Encourage skepticism in context

Children’s skepticism is context-specific. My colleagues and I have demonstrated, for example, that even four-year-olds show rudimentary fact-checking abilities in digital contexts—under the right circumstances. When they notice that a platform contained some misinformation in the past, they seek out more evidence before accepting a new claim. Conversely, children who never see anything wrong do almost no fact-checking at all.

The key insight here is that children’s early interactions with a platform set the tone for how trusting they are. Show your child that you sometimes question the information that comes from the same platforms that they use. For example, if you come across a suspicious AI summary on Google, comment on it out loud. Narrate the process of lateral reading, or how to cross-check a claim with different sources. Explain that AI is often wrong because it works by guessing what words should come next, and not by actually thinking or reasoning.

Co-viewing media with your child can help bring the conversation into their world. One starting point is advertisements, which are rampant in kid-oriented content. Take a moment to discuss advertisers’ motives and how to distinguish impartial from persuasive content. Reasoning about this kind of bias can be difficult well through the tween years, but research suggests scaffolding can help.

Practice strategic disengagement

Critical thinking is slow and deliberate. Scrolling through a social media feed is quite the opposite. Even when a questionable post raises alarm bells, that inkling of skepticism might vanish the moment a newer, shinier piece of content appears. Parents can help children learn when to slow down and reflect. Enforcing frequent breaks or time limits can curb the habit of endless, passive consumption. Children’s screen habits tend to reflect their parents’, so when possible model the behavior you want to see.

Another simple strategy is to teach children that if something arouses strong emotions, they should pause. Sensational headlines and rage bait are designed to exploit Internet algorithms, and are good signals to disengage, question the content or get a parent’s opinion. In general, fostering slower, more intentional digital habits can lay the groundwork for children to put their burgeoning critical thinking skills to good use.

Ultimately, kids’ presence in the digital landscape is a reality. We can help mitigate the risks associated with their presence by guiding them toward better digital habits now, giving them the best possible chance of surfing the Web independently in the future without getting swept away. Like real surfing, starting young—and with a good instructor—may teach kids to keep their balance and steer clear of the roughest waves.