Now Reading: Madhav Gadgil: Hope for Change as Vanishing Hills Raise Alarm

-

01

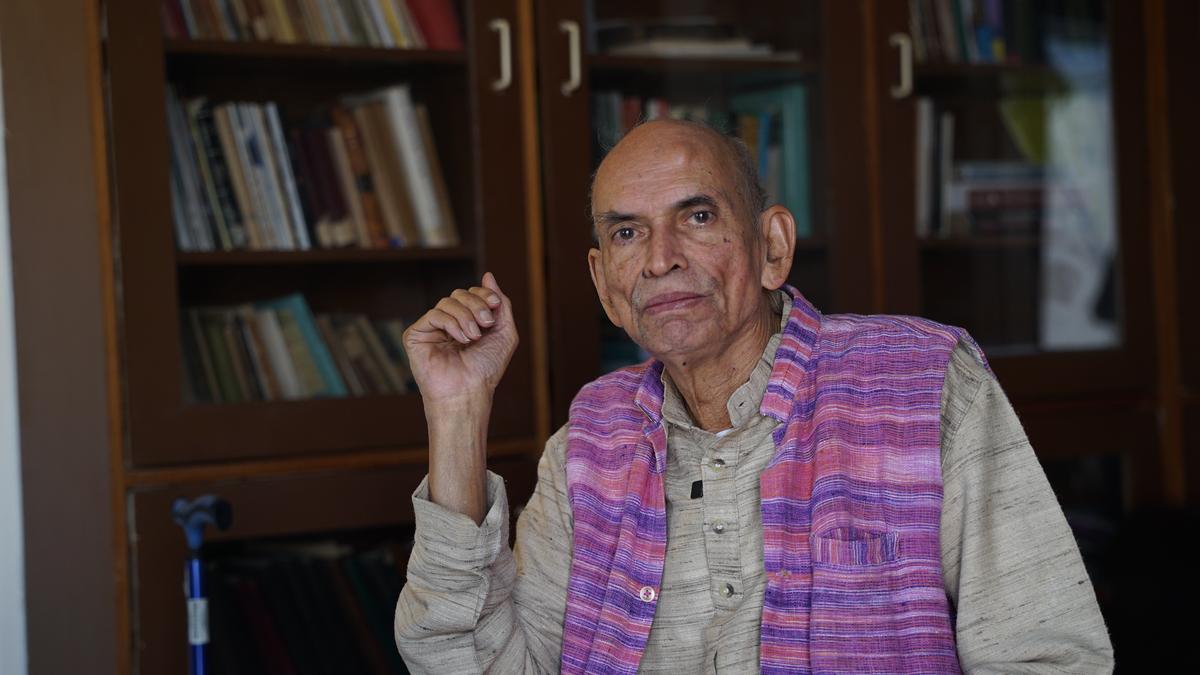

Madhav Gadgil: Hope for Change as Vanishing Hills Raise Alarm

Madhav Gadgil: Hope for Change as Vanishing Hills Raise Alarm

Quick Summary

- Padma Bhushan awardee Professor Madhav Gadgil, a leading ecologist, emphasized the need for ecological preservation and community-focused decision-making.

- Speaking after receiving UNEP’s ‘Champion of the Earth’ award, Gadgil highlighted tragedies like the 2024 Meppadi landslide in Wayanad as preventable disasters linked to unchecked ecological destruction.

- Data shows landslides in India’s Western Ghats increased by 100 times between 2010 and 2020 due to fragile ecosystems and human activities such as rock quarrying and unregulated development.

- Recommendations from the Western Ghats Ecology Expert Panel (WGEEP) report in 2011 included restrictions on construction, quarrying, and infrastructure development-but were largely ignored or diluted by subsequent committees.

- gadgil criticized economic projects like petrochemical complexes and industries that displace vulnerable communities while degrading natural habitats-citing examples from Maharashtra’s Konkan coast to illegal mining operations in Goa.

- He expressed frustration with governance structures that exclude local communities from decisions impacting their livelihoods and ecological rights under laws like the Forest Rights Act (2006).

- Gadgil urged grassroots empowerment for tea estate laborers across India who disproportionately bear disasters’ impacts due to inequitable land ownership systems. He called for greater use of technology for mobilization among workers nationwide.

Indian Opinion Analysis

The recurring theme of professor Madhav Gadgil’s analysis is systemic neglect toward vulnerable ecosystems like the Western Ghats-and its direct impact on marginalized populations such as forest-dwellers, fisherfolk, plantation workers, and small landholders. The crux lies not only in environmental degradation but also unequal socio-economic outcomes stemming from poorly regulated industrial activity or mismatched economic policies designed at macro levels without consulting local stakeholders.

India’s challenge remains balancing rapid growth aspirations with sustainable practices rooted deeply within existing legislation-such as the Forest Rights Act (2006)-to safeguard both biodiversity hotspots and people dependent upon them for survival. Gadgil highlights how ignoring scientific recommendations can result in devastating consequences felt most acutely by poorer sections without resources needed to recover quickly after climate-induced calamities like floods or landslides.

His call for participatory governance involving empowered Gram Panchayats underscores continued reliance on democratic institutions to drive equitable change-a sentiment echoed globally where decentralized models have succeeded elsewhere (e.g., Switzerland’s reforestation efforts).Integrating AI-driven tools may reduce communication barriers among affected groups; however, broader action will require legal enforcement of environmental standards coupled with openness against corruption widely exposed by reports he referenced.

Gadgil invokes a hopeful vision but frames urgency sharply: Unless systemic reforms prioritize ecology alongside people-centered economic reforms backed rigorously through active policymaking-repeated disasters may well strain India’s fragile socio-environmental fabric further toward tipping points detrimental nationally.___