Now Reading: New evidence may expose Queen Victoria’s affair with servant John Brown

-

01

New evidence may expose Queen Victoria’s affair with servant John Brown

New evidence may expose Queen Victoria’s affair with servant John Brown

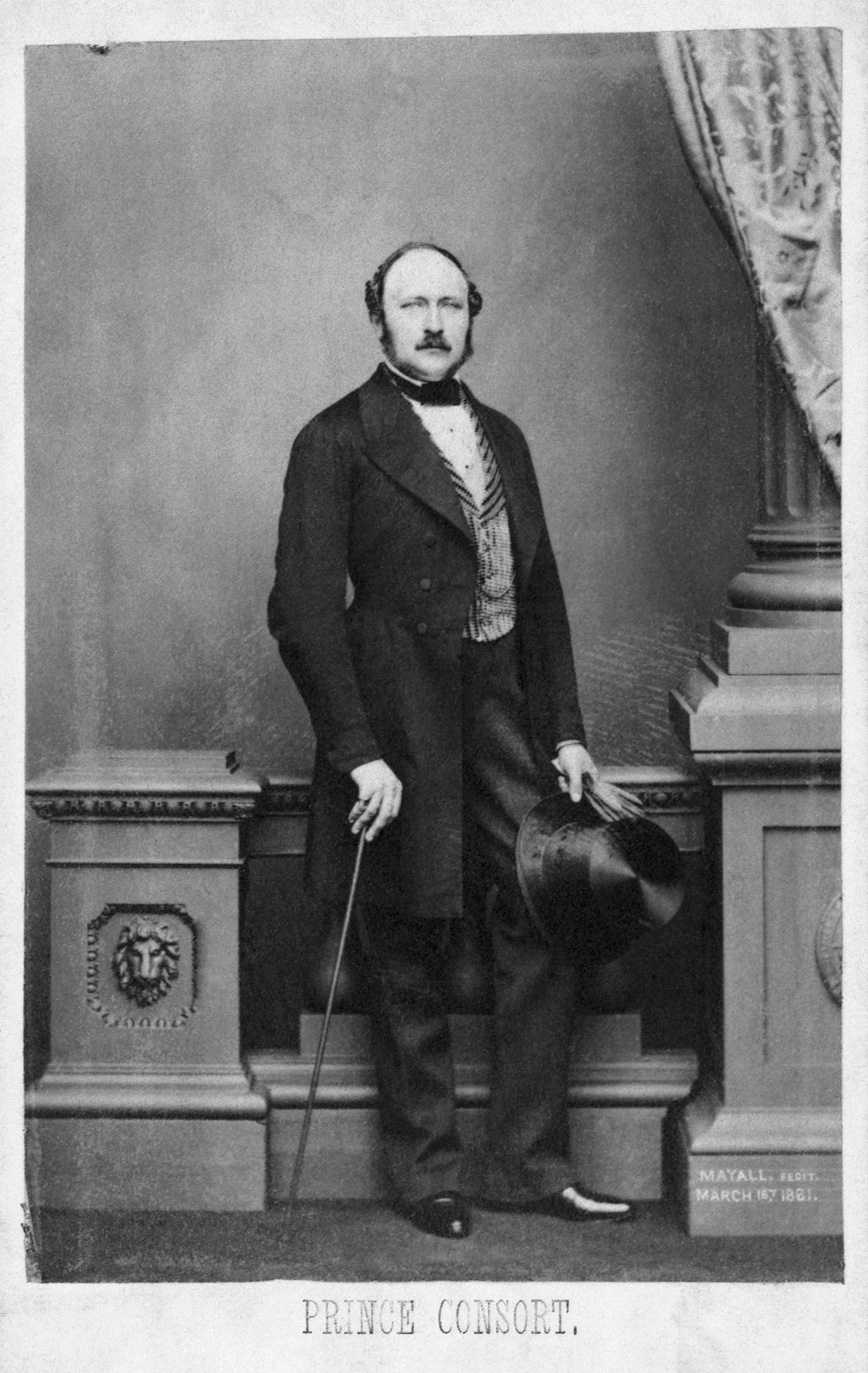

When Queen Victoria died in 1901, she was laid to rest with photographs of her family and mementos from her husband and consort, Prince Albert, who had passed 40 years earlier. Tucked into her coffin were Albert’s handkerchiefs and a marble sculpture made from a cast of his hand. Her devotion into the grave is no surprise: Victoria has spent four decades publicly grieving his death, wearing mourning clothes, and lavishly commemorating Albert’s life.

But it wasn’t just Albert’s mementos she sought in death: she also wanted a photograph of her longtime servant John Brown, locks of his hair, and his mother’s wedding ring. Brown, a Scot employed at Victoria’s Scottish estate Balmoral, had spent almost two decades constantly at Victoria’s side, emerging as her closest companion after Albert’s death. At the time, only her doctor and ladies-in-waiting knew about her desire to be buried with Brown’s effects, but nevertheless, for 160 years, rumors have swirled about the precise nature of the relationship between Victoria and Brown. Was he a particularly devoted servant? A platonic male shoulder to lean on in her grief? Or did the pair have a romantic relationship?

The rumor has fascinated historians for over a century, each generation arguing over scraps of evidence, reinterpreting the relationship and reshaping their knowledge of Victoria and her era. Victoria’s own writings have fueled the speculation, too: “Perhaps never in history was there so strong and true an attachment, so warm and loving a friendship between the sovereign and servant,” she wrote in a letter after he died.

Historian Dr. Fern Riddell recently entered the debate with her new book Victoria’s Secret: The Private Passion of a Queen and its accompanying documentary, which claims to reveal new evidence about Victoria’s and Brown’s relationship. Riddell tells a compelling story filled with midlife passion, gossiping courtiers, and resentful adult children.

“It’s got everything—it’s tragedy, it’s high romance, it’s love across a huge social divide, it’s the secrecy of it,” Riddell tells National Geographic. “And when you look at it closely, it’s the story of a man who was absolutely devoted to the woman that he loved. And that’s very powerful for us today.”

Riddell’s cheekily named book is part of a 21st century attempt to correct the historical record. Since the moment she was laid in her grave, Victoria has been remembered as a stern, remote, even prudish monarch in voluminous black dresses. But her posthumous reputation is a far cry from the flesh-and-blood realities of her life.

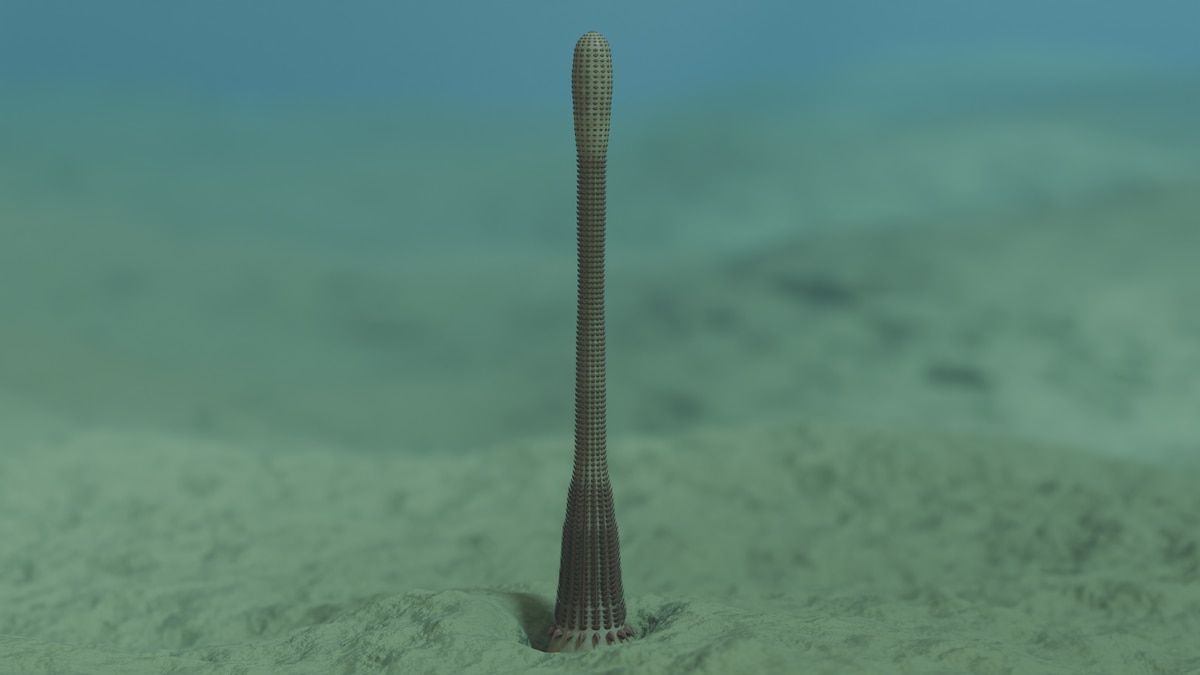

A 1864 photograph of Victoria and John Brown. Brown worked as a ghillie at Balmoral, the Queen’s estate in Scotland, and was rumored to have had an affair with Victoria.

The long-standing rumors about Mrs. Brown

The rumors started shortly after Victoria was widowed.

Avoiding the British public and frustrated with her ministers, she retreated to solitude at the picturesque Balmoral, an estate she’d built with Albert in 1852. Brown had worked at Balmoral for years as a ghillie, an attendant on hunting trips but, by 1864, Victoria had promoted him, giving him the official title of Queen’s Highland Servant—“to remain constantly in attendance upon the Queen,” according to the memorandum Victoria issued to Brown. In the years that followed, Brown was constantly at Victoria’s side, accumulating enormous sway within her household.

Her courtiers started talking, and then the gossip spread into the boisterous print culture of 19th century London, with satirical magazines publishing sly items about Brown’s omnipresence; The Tomahawk, for instance, published a cartoon of Brown leaning on an empty throne, gazing down on an attentive British lion.

Most explosive was an 1866 report from the Swiss Gazette de Lausanne, which suggested that not only was Victoria—so thoroughly secluded since Albert’s death, so far from the public eye, routinely missing important ceremonial occasionals like the opening of Parliament—involved with Brown, but more scandalously, she’d become pregnant. “They say… she is in an interesting condition and if she didn’t attend the Volunteers review and the unveiling of Prince Albert’s memorial, that would be only to conceal her pregnancy,” the paper reported.

Victoria did little to squelch the rumors. Instead, she commissioned a large-scale painting by one of Britain’s most important painters, Edwin Landseer. Shown at the Spring Exhibition of the Royal Academy, a major cultural event, Her Majesty at Osborne (1866) showed Victoria in her customary black, atop a horse guided by Brown, official papers littering the ground, in full view of the titillated British public. “If anyone will stand by this picture for a quarter of an hour and listen to the comments of visitors he will learn how great an imprudence has been committed,” wrote a contemporary art critic.

Victorians widely gossiped about the Queen’s romance and even a possible love child, dubbing Victoria “Mrs. Brown.”

The coverup

In 1883, Brown died suddenly at the age of 56. Once again, Victoria mourned, closing Brown’s rooms, pouring out her sadness in her correspondence, and commissioning various memorials, but unlike Albert, where her grief left a trail across modern London, posterity began minimizing Brown.

First, her advisors talked her out of privately publishing a memoir about Brown (the draft was later destroyed); it was already bad enough that she’d dedicated the second volume of selections from her Highland journals to him. Then, when Victoria died, she left care of her journals to her youngest daughter who spent years heavily editing the volumes and burning the originals. Victoria’s letters, meanwhile, were edited for publication by two men with their own agendas, who weren’t interested in things like pregnancy or motherhood, shaping her image for decades to come. And her eldest son Bertie, who became Edward VII, immediately turned Brown’s chambers into a billiard room and purged all the reminders of the Scottish servant, including the numerous paintings and busts that his mother had commissioned over the years.

After her death, “Victorian” came to be synonymous with prudery, while Victoria herself was reduced to a black-clad, elderly great-grandmother, head topped with a fussy bonnet, perpetually unamused, never mind that she did have nine children.

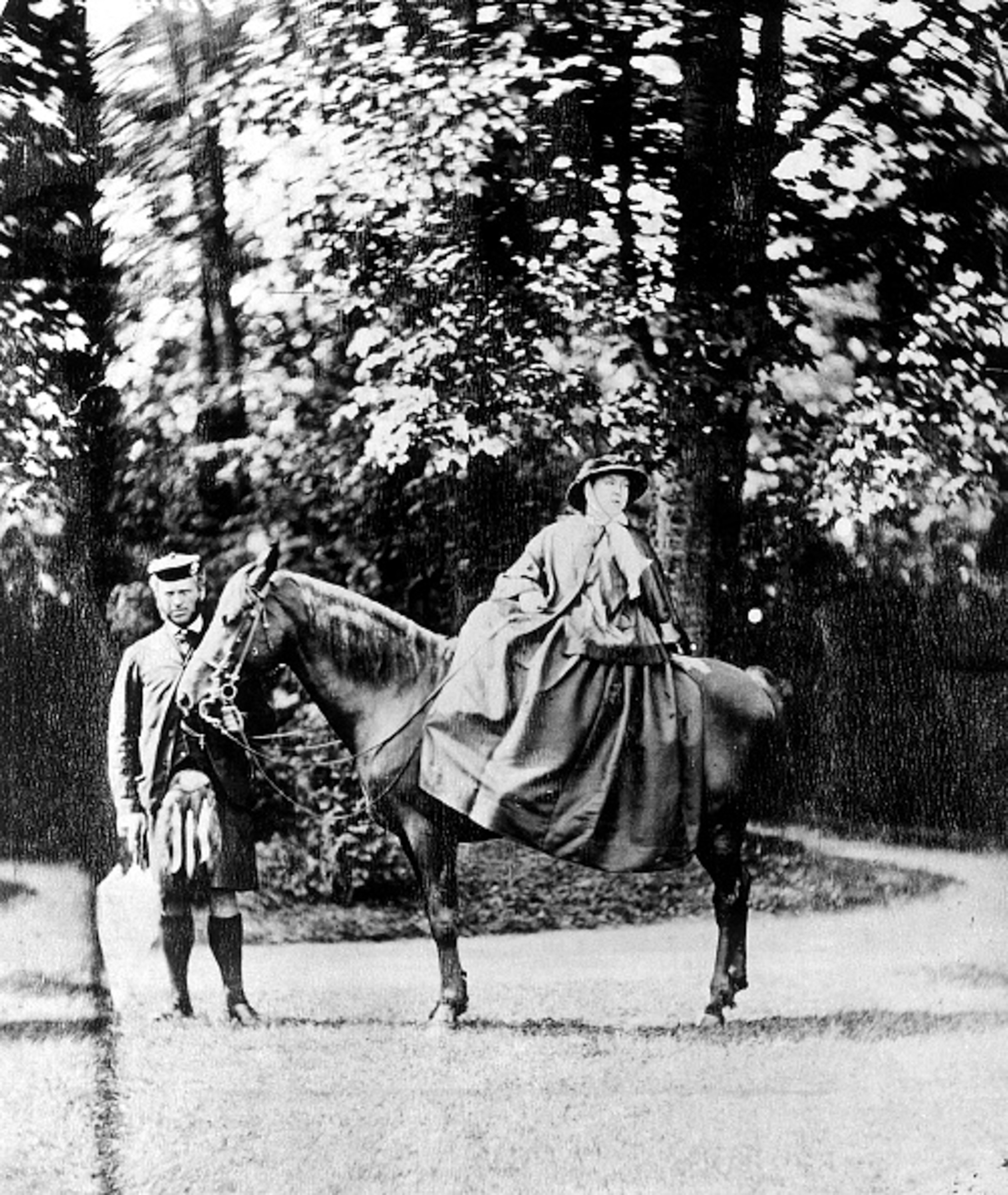

John Brown circa 1865. His relationship with the Queen was the source of endless Victorian gossip, leading many to dub Victoria, “Mrs. Brown.”

Photograph by W. & D. Downey/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Prince Albert, Queen Victoria’s consort, photographed before his early death in 1861 at age 42. Victoria was buried with many of Albert’s mementos, including a marble sculpture taken from a plaster cast of his hand.

Photograph By Hulton-Deutsch Collection/Corbis/Getty Images

The rumors persist into the 20th century

Despite the attempts by posterity to purge Brown from public memory of Victoria’s reign, stories about “Mrs. Brown” continued to fascinate. Tantalizing hints also emerged over the course of the 20th century, Victoria’s contemporaries dead long enough that their diaries, letters, and other papers became public. The world could finally read politician Lord Derby despairing over her lack of propriety with Brown, rattling off in his journal about the relationship:

Long, solitary rides, in secluded parts of the park: constant attendance upon her in her room: private messages sent by him to persons of rank: avoidance of observation while he is leading her pony or driving her little carriage.

The princesses, Derby added, referred to Brown as “Mamma’s lover.”

You May Also Like

Tom Cullen’s 1969 book, Empress Brown, included a facsimile of a letter from Victoria to Brown’s brother after his death, recounting a conversation in which they pledged their devotion to one another: “Afterwards I told him no-one loved him more than I did … and he answered ‘nor you – than me … No-one loves you more.’” The book suggested the existence of more evidence from Brown’s own family, but his descendants refused access to any of it, with rare exceptions.

The evidence piled up, even as historians continued to express skepticism or at least to point out the difficulty of knowing exactly what these two meant to each other, like Victoria’s instructions for her burial arrangements. But the steady drip of stories kept the notion of Mrs. Brown sufficiently alive that in 1997, it was fodder for a historical drama that garnered Judi Dench a Golden Globe for her performance as Victoria—though a review of the movie described it as “willfully discreet.” (Screenwriter Jeremy Brock was one of the few people who got a look at the Browns’ archives, until now.)

Reassessing Queen Victoria, the woman

In recent years, increasingly, there’s been a reassessment of Victoria. Books like Yvonne M. Ward’s Censoring Queen Victoria, Lucy Worsley’s Queen Victoria, and Julia Bard’s Victoria: The Queen, have attempted to excavate the woman from the monarch and her public image. They’re increasingly frank about the realities of Victoria’s life as a woman, including her desires, the toll taken by so many pregnancies, the postpartum depression, even her rocky experience of menopause.

We know now, for example, that Victoria dreaded pregnancy and struggled with severe postpartum depression. She was physically very attracted to her husband: “his love and gentleness is beyond everything, and to kiss that dear soft cheek, to press my lips to his, is heavenly bliss,” she wrote in her journal just days after they married.

That reassessment extends to the topic of her relationship with Brown: “There are few subjects as wildly speculated about and poorly documented as Queen Victoria’s relationship with John Brown,” writes Baird. Still, she concludes: “What is certain is that Queen Victoria was in love with John Brown.” Meanwhile, Worsley is skeptical that their relationship was a sexual one, chalking the scandal up to “the unspoken belief that a widowed woman of middle age, as Victoria was, must inevitably become sexually insatiable.”

The royal family is still staying silent on the topic of Mrs. Brown. As Baird revealed in her book, researchers who use the Royal Archives are required to agree that any quotes and “all intended passages based on information obtained from those records” must be submitted for approval. And she was asked to remove “large sections” from her book based on material found outside the archives, including Victoria’s requests for the items in her coffin.

Riddell enters the chat

Riddell wades into the debate with a new approach, re-examining the existing evidence while looking much more closely at Brown, his family, and the community around Balmoral. “I’ve always been fascinated by the idea that there was this man from a crofting farmer’s family who stood at Victoria’s side, the most powerful woman in the world, at this point, for 20 years, and we knew so little about him,” Riddell says.

And she finally confirms the existence of that letter from Victoria to Brown’s brother, as well as the Brown family archive, hinted at in Cullen’s Empress Brown, much of which is now accessible at local archives in Aberdeen — and reveals much more about its content. For instance, Victoria had a cast made of Brown’s hand just after his death, nearly identical to the one she had made of Albert’s. There’s also a New Year’s card inscribed, “To my best friend JB / From his best friend V.R.I.” (V.R.I was Victoria’s royal cypher, meaning “Victoria Regina Imperatrix.”)

Pointing to an account of a deathbed confession by Victoria’s royal chaplain of marrying the pair and Victoria’s documented behavior regarding Brown, including her demands that her sons shake his hand, as though he were their social equal, Riddell makes the case that Victoria and Brown likely had an “irregular” marriage. Scottish marital customs were notoriously flexible at the time, and it had become common for couples to “marry” by simply swearing vows.

“We’d only ever considered this possibility of a marriage from an English lens—there had to be a priest, there had to be marriage banns, there had to be a church wedding,” says Riddell. “No one had ever considered it from his community’s perspective.”

Most interesting is Riddell’s discovery of an enduring Brown family story which tells of a child. Angela Webb-Milinkovich, a pierced and tattooed care worker from Minnesota descended from Brown’s brother Hugh tells Riddell: “We were always told that we were the illegitimate line.” Hugh and his wife emigrated to New Zealand in the mid-1860s and registered a daughter’s birth, the couple’s only child. The couple stayed for only a decade, returning to the United Kingdom in the 1870s, child in tow. Their return trip was paid for by Victoria.

There are plentiful reasons to be skeptical about a potential secret child—family stories about lineage are often unreliable, and Victoria was in her early 40s when her relationship with Brown developed. Plus, Victoria suffered from a painful injury, a prolapsed uterus, that her doctor discovered only after her death. But Riddell argues that none of that rules out the possibility that Victoria had another child. “There’s no evidence to support the idea that she had a prolapsed uterus immediately after [her youngest child’s] birth,” Riddell says, and it’s common for the injury to happen later in life.

Nor was she too old: “Many women in this period have their last baby between 45 and 47,” Riddell says. Plus, a pregnancy would have been easier than many might assume to conceal. Victoria was deep in seclusion, wearing voluminous mourning gowns. “No one saw the queen naked. No one touched her body, apart from the four women who were her dressers,” says Riddell.

Of course, there are Victoria’s own words. She was famously vocal about her difficulties with pregnancy and doctors had advised Victoria not to have any more children over concerns about postpartum depression. But after Albert’s death, Victoria longed, one of her daughters wrote, “for another child.”

Proof, though, would be difficult to establish. When it comes to DNA, “it’s much more complicated and much more delicate than television and culture has given us the impression of,” says Riddell, who makes no definitive claim regarding the story, simply presenting the evidence for and against. But what does become clear in Riddell’s book is that Brown’s own family understood that a relationship existed.

The rumor of Mrs. Brown will no doubt endure; it’s just too tempting to speculate about the private lives of the powerful, particularly when the details are so at odds with the public image. What Victoria’s contemporaries saw between the monarch and her Highland Servant says as much about their society’s fears, preoccupations, and messy realities as it does about these two individuals, and the modern fascination is no different. Everybody wants to know what happens behind closed doors, especially palace doors.