Now Reading: Robert Redford rides the Outlaw Trail

-

01

Robert Redford rides the Outlaw Trail

Robert Redford rides the Outlaw Trail

This cover story originally published in the November 1976 issue of National Geographic magazine.

I rode hard to reach the campsite near Hole-in-the-Wall before dark. After an intense year of filming All the President’s Men, it felt good to shake the city dust from my bones. On a distant ridge a few aspens still struggled to hold their awesome yellows against oncoming winter, and the October wind stung me into an alertness I hadn’t felt for months.

Hole-in-the-Wall, for years a notorious refuge for rustlers, killers, and thieves, is a narrow notch in the great Red Wall of central Wyoming. When I reined up, others were already camped in the dry, sloping valley below, milling around a fire; young faces and old, some weathered by the elements under sweat-stained stetsons curled to the owners’ liking.

From this rendezvous we would set out to retrace a major, 600-mile segment of a historic, rugged route—often glorified, in places still mysterious or long erased—known as the Outlaw Trail.

As technology thrusts us relentlessly into the future, I find myself, perversely, more interested in the past. We seem to have lost something—something vital, something of individuality and passion. That may be why we tend to view the western outlaw, rightly or not, as a romantic figure. I know I’m guilty of it, and for years I have been fascinated by that part of the West that offered sanctuary and escape routes to hundreds of colorful, lawless men.

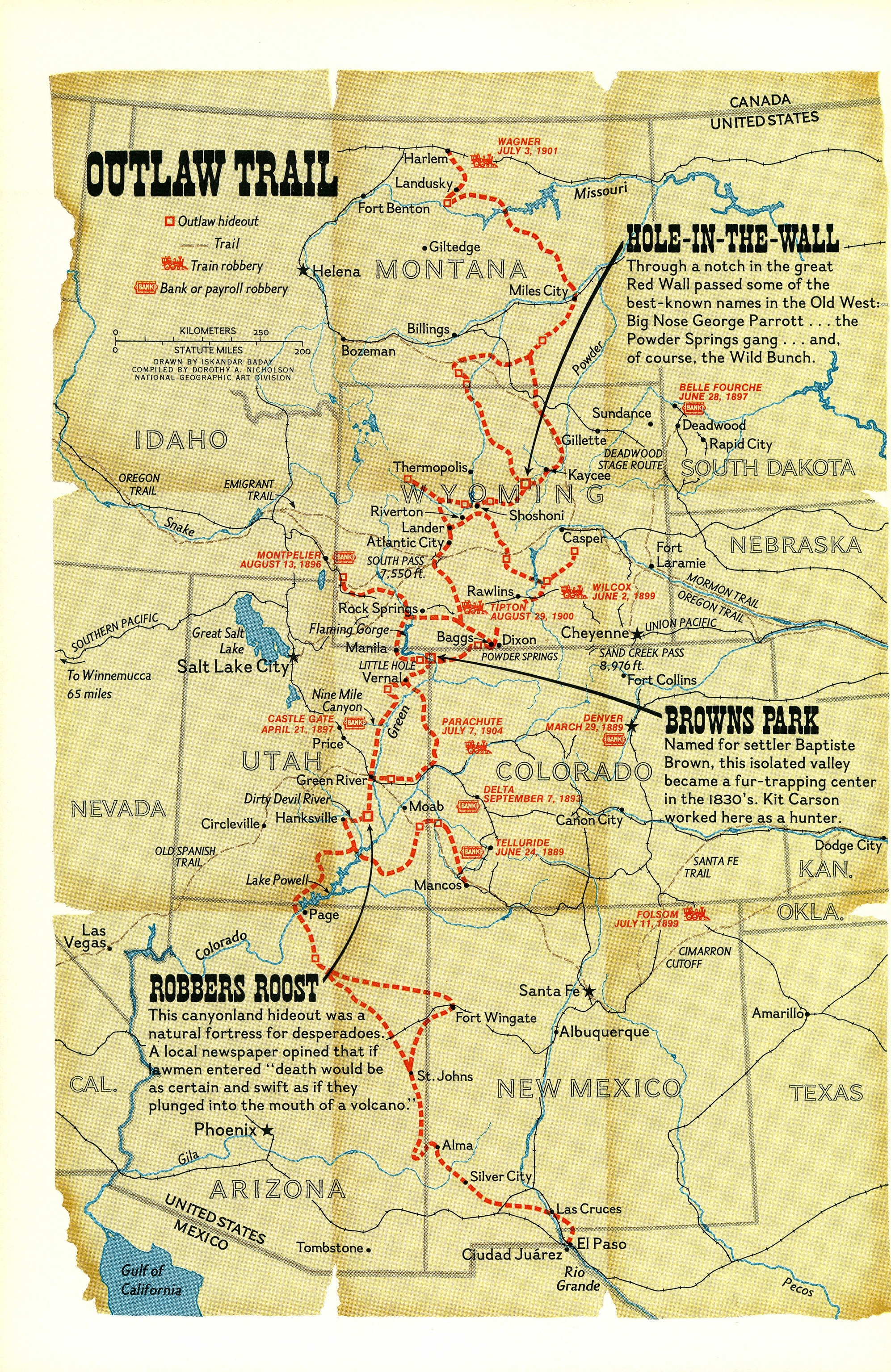

The Outlaw Trail actually ran from northern Montana to Mexico. It had dozens of offshoots, but the main stem wound from Montana south and across Wyoming, through Utah and part of Colorado to Arizona and New Mexico, southeast toward Texas and the Mexican border.

Map from November 1976 article

For some forty years, beginning about 1870, it was a lawless area where a man with a past or price on his head was free to roam nameless. But he had to be good with a gun, fast on a horse, and cleverer than the next. On this trail no holds were barred, and old age was a freak condition.

I had heard tales of what survives in this country, forgotten or buried by time: old graves, cabins, caves, saloons, whole towns now untended. I’d heard stories of the outlaw bands and notorious men who rode the trail: the Red Sash gang, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, Jesse and Frank James, the McCarty brothers, Matt Warner, Big Nose George Parrott, Nate Champion, Tom Horn, and many others.

Inventive Outlaws Made Crime Pay

The most efficient and elusive outlaw gang in the history of the American West was the Wild Bunch, numbering anywhere from three to ten, with up to a hundred hangers-on. They rustled cattle, stole horses, robbed banks and payrolls, and held up trains in half a dozen states for about six years around the turn of the century.

The gang dissolved after its undisputed leader, Butch Cassidy, and his sidekick Harry Longabaugh (the Sundance Kid) sailed for South America. There, according to some historians, the two were cornered and killed by Bolivian soldiers.

Butch Cassidy and his crew were masters of the “pony express” concept for their get aways—using fresh horses and supplies posted at a network of way stations about twenty miles apart. The most important of these on the Outlaw Trail were Hole-in-the-Wall, Wyoming; Browns Park on the border between Utah and Colorado; and Robbers Roost in Utah. Caches of weapons were kept at strategic locations. Outlaw post offices for letters and messages were hollow trees, holes or ledges, or chinks in log cabins.

By this system a robbery could be perpetrated near Rawlins, Wyoming, on Monday, and the outlaws could be 120 miles away in Browns Park, Utah, on Tuesday, leaving the law baffled as to how it was accomplished.

For the trip I had in mind, I had invited eight companions, mostly unacquainted and from different places and backgrounds. But they did share a deep love of the outdoors and an interest in western history.

They included photographer Jonathan Blair and his wife, Arlinka; Dan Arensmeier, a Fort Collins, Colorado, marketing consultant and his wife, Sherry; and Kerry Ross Boren, a western historian from Salt Lake City. Three of the group would join us along the trail: Terry Minger, town manager of Vail, Colorado; Edward Abbey, a novelist and naturalist from Moab, Utah; and Kim Whitesides, a Utah artist and old friend of mine, now transplanted to New York City.

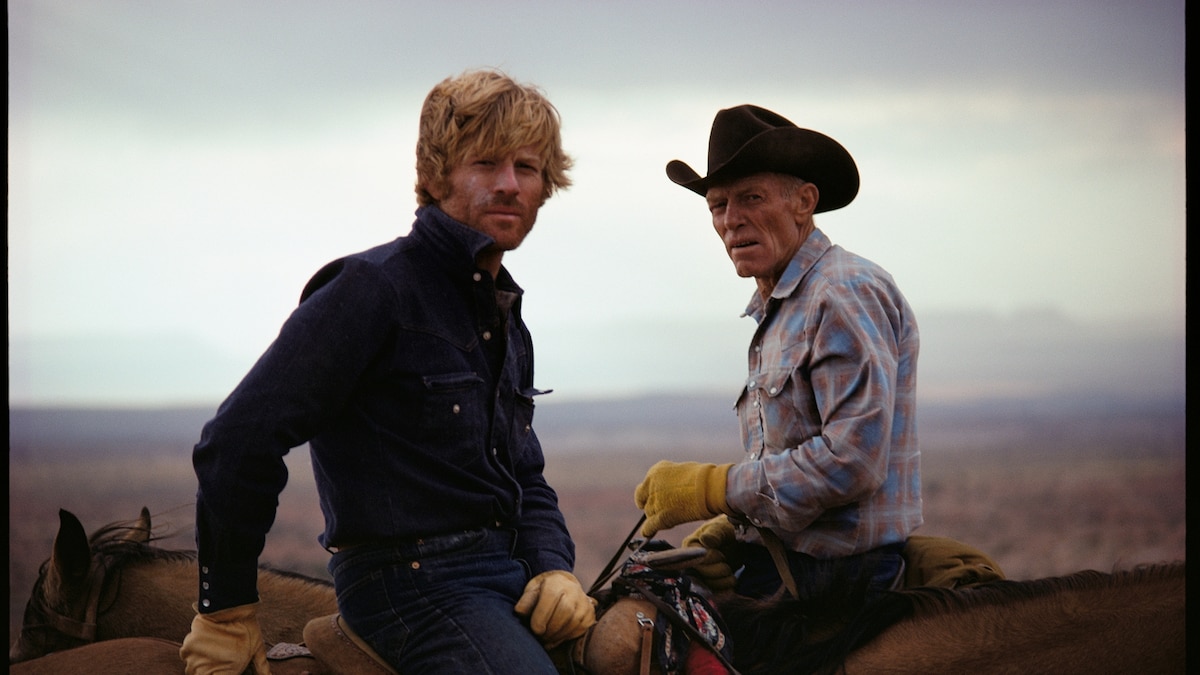

Our guides for Hole-in-the-Wall, starting point of our trip, were Garvin Taylor, 59, and his son Curt, who run the Blue Creek Ranch. Around that first night’s campfire, Garvin proved himself an artist of his kind—nonstop western raconteur with an impressive fund of saddle wisdom. He had led a rich and varied life, and admitted to having been an outlaw once himself.

Someone kidded Garvin about his new Levi’s. “Still stiff,” he answered. “Got to stand ’em against a tree to put ’em on.”

He spoke of the Hole-in-the-Wall area.” Ain’t no place like it. This place has its own ways—ways dictated by the outlaws who settled it. Ain’t nothin’ much changed.”

A grizzled old cowhand rode into camp looking as though he had consumed an entire distillery. His name was Tex, and he tends cows for the Taylors. He had tangled with a bank clerk in San Antonio in 1927, I was told, and fled to Hole-in-the-Wall. He’d been in the area ever since.

A bottle made the rounds. Everyone was mellowed out now, the fire, the food, and the drink a settling force. The talk turned to more serious matters.

Curt Taylor seemed to be the spokesman for the group, and he was worried about the future: “What’s happening to the rancher in this area? Ranchers are one of the smallest minorities there is—damned few and gettin’ fewer. I’d make more money if I sold and lived on the interest.”

“Why don’t you?”

“Nothin’ short of foreclosin’ would pry me out. I love the land, I love this place. It has a fabulous history. I guess we feel part of it, me and my dad.”

Rising Costs Force Ranchers Out

He described a common rancher’s dilemma, one we’d hear about repeatedly during the ride: Coal, oil, gas, or power companies will buy up an attractive ranch and trade it for land they really want in mineral areas. They pay the rancher a good price, but this raises the assessed value of his neighbors’ land—as well as their taxes. Other ranchers are then tempted to sell, and so a slow squeeze play is set in motion.

“Evaluation is a hundred dollars an acre here now,” said Curt. “Taxes and production costs will kill you. You make only two-thirds of what it costs you to raise a cow.”

Other local people around the fire murmured their assent. Someone spoke of growing Government intervention and regulation in the West:

“Gettin’ so if you want to spit these days, you need a permit.”

“Yeah, and you got to dig a hole first.”

“They probably got a handbook on that, too—How to Dig Your Hole.”

“I don’t need no handbook,” rasped Tex, suddenly alive again. “My life is a dug hole.”

It was already 1 a.m. The temperature had dropped below freezing, and snow was beginning to fall. Some had crept away to sleeping bag, bedroll, or tent.

The ground was hard and cold. I had mistakenly brought my son’s sleeping bag, and it was too small to stuff myself into. I cursed my carelessness and dozed off thinking of the cowboys who spent months like this, back when there were no down sleeping bags, hand warmers, snow boots, or thermal underwear. I thought about that—about hard ground and hard bones and the saddle for a pillow.

Cowboy Coffee Cures the Stiffness

Morning. We had all gone to bed to the sound of Tex’s voice, and now we woke up to it, like musical accompaniment. Except it sounded more like a cattle wagon being dragged over a dry river bottom.

The fresh smell of cowboy coffee to cut the dead chill of dawn. The sizzle of bacon and sourdough pancakes. The awakening of voices, the sound of saddle leather, utensils clattering, stiff-body groans, and a lot of coughing from the old-timers.

Redford and campers eat breakfast during their trip across the Outlaw Trail, near Hole-In-The-Wall Gorge, Wyoming.

Someone was cooking eggs. Tex: “The chicken is the only thing we eat before it’s born and after it’s dead. …”

After breakfast Garvin led the ride up the sloping valley to the actual Hole-in-the-Wall—the V-shaped opening at the top of the red-stone escarpment, barely wide enough for a horse. There, two men with Winchesters could stand off an army.

On the way we saw virtually nothing of the old outlaw “ranch”—once a few crude log huts, tents, a saloon—in which rustlers and other outlaws gathered in the past century.

There was good grass here to fatten stolen cattle and horses. Garvin pointed to a spot on the trail where a rustler was shot by a group of cattlemen.

I asked about the famous Johnson County War. In April 1892, Cheyenne cattle barons imported a gang of 20 gunfighters from Texas to clean out this part of Wyoming of rustlers and small cattlemen alike. But the “invaders” were held to a stalemate. It took the U.S. Cavalry to rescue them from a countersiege by a force of irate settlers and outlaws.

I had read a film script that told of at least a hundred people shot in the war. “That’s a lot of puckie,” Garvin said. “Only four was killed. Nate Champion and Nick Ray was ambushed in a cabin right over there.” He pointed to a distant flat. “One guy shot himself in the foot and got gangrene. Another died from something else. But hell, there was more people shot in a poker game in Gillette.”

The climb up the wall to the niche, or hole, was steep and a little dangerous over the loose rubble. The rest of us dismounted and led our horses the last third of the way, but Garvin rode right to the top. A horse can sense when a real horseman is in the saddle. Garvin’s horse knew. He never balked.

As we rode across the flats stretching endlessly toward a gray-black horizon, I put up my collar and turned down my hat against the chill wind. Garvin rode gloveless, with only a denim jacket to protect him.

From a mesa we surveyed the Middle Fork Powder River Valley far below—now threatened by development.

“Water is a very big issue here,” said Curt.

“Oil interests want to build a dam, flood this valley, and send water 75 miles away to Gillette for coal-gasification plants. They’d get more than two-thirds of the water; the rest would be used for irrigation. But the dam would bring more and more people, and Hole-in-the-Wall, as we know it, would be a thing of the past.”

He was bitter as he spoke. There is something unhappy here, I thought, something unsettling—a fear that a way of life is dying, and with it, a certain dignity.

We went on to the Blue Creek Ranch to meet Mrs. Ethel R. Taylor, Garvin’s mother, a sweet, spirited woman in her 80s. You could immediately sense in her a pioneer spirit—a tough, durable sensibility.

“Many people from around here come from outlaw backgrounds,” she said. “Sometimes they leave mysteriously … we don’t ever ask why … we’re proud of it.”

When we said our goodbyes, I thought Mrs. Taylor had the strongest handshake.

No Seashore in Atlantic City

Our trail took us to Shoshoni, Riverton, Thermopolis, and finally to Lander, at the foot of the beautiful Wind River Range. Around here, early in his outlaw career, Butch Cassidy had passed himself off as a horse dealer; some noticed, however, that he was always selling, never buying. Kerry Boren, our historian, said Cassidy was supposed to have cached $30,000 in these mountains.

Just outside Lander on the climb to the Continental Divide is the small, all-but-forgotten settlement of Atlantic City, an old gold-mining town. A dirt road led us into a cup of a valley where, to our amazement and joy, nothing seemed to have changed for nearly a century. A few tiny cabins stood like wooden sentries against stark brown-and-white slopes.

A few dozen people live hereabouts, but there is only one hub of activity in Atlantic City—the Mercantile, a combination bar and general store. We walked up its worn steps and were instantly cast back in time: potbellied stove, photographs of suspendered store clerks with high collars and mustaches and cowboys with fresh haircuts that left the ears naked and the scalp pale around them, staring wide-eyed into the camera.

Here Terry Minger was waiting to join our party. Beer in hand, he introduced us to Terry Wehrman, who tends bar and acts as city councilman, mailman, cook, father confessor, and keeper of goodwill in Atlantic City. He is one of many young men and women who are striking out on their own.

Terry Wehrman, a transplant from Iowa, is shy, gentle, and openhearted. “I’m worried about the developing interests, sure,” he said. “The Anaconda Company, for instance, took out leases on some of the old gold mines and staked for other minerals as well. U.S. Steel has a mine here for iron ore.

“If the development gets too great, I’ll relocate. I’m hoping it doesn’t. You see, the good thing about Atlantic City is that it’s a ghost town and no one wants it. But it has attracted some good people—young ones who don’t want to work for anybody else but are willing to build something for themselves.”

Listeners Always Welcome at the Bar

Not all were young newcomers. Over at the bar, in Pendleton shirt, suspenders, and straw hat, was an old-timer named Larry Roupe. I asked if I could buy him a beer. He squinted at me and said, “Who the hell are you?” He sounded like a frog with laryngitis.

I told him I was just passing through the area and wanted to know more of its history.

“Sure, you can buy me one.” I wanted to listen; that was enough for him.

“I came from Oregon in 1922 on the Emigrant Trail,” Larry said. “My dad was a cattle buyer—he’d go down to Texas, buy steers for two dollars a head, then bring them up to Wyoming and sell them.

“I was just a kid then, but I loved this country. I ran cattle for a while, then took to rodeoin’.”

“Were you ever an outlaw?”

“No, I never went that way. I could have—could’ve been a good outlaw. But I jes’ never went that way.”

“There were a lot around these parts, weren’t there?”

“Oh, yeah—all over.”

“Even in 1922?”

“Hell, yes, later’n that … I could tell you stories.”

The talk turned to Butch Cassidy.

“He was the best, the smartest,” Larry said

“Know how he got the name ‘Butch’…? Worked in a butcher shop over in Rock Springs. His real name was Parker.”

“Yes,” I said, “Robert LeRoy Parker.”

“Yeah …” he seemed surprised I knew. “LeRoy Parker Butch and his boys hung out mostly over ’round Baggs and Dixon, Wyoming. The ranchers all liked Butch. He was good to them. The real bad one was Harvey Logan. Jes’ as soon kill you as look at you. Harvey used the alias Kid Curry. He killed old Pike Landusky up there in Montana … then he robbed this train down at Wilcox.”

Slow Trains for Quick Holdups

Larry assumed everyone knew who and where these people and places were. The small world of the cowboy.

“Why were there so many outlaws here?”

“Well, there was gold here, and it was easy to rob stagecoaches and trains then … they’d jump them trains when they was slowed goin’ up a grade, then they’d hold ’em up.”

He sipped his beer. “I could tell you lotsa things about this country—like the ‘big die-up.’ That was the big blizzard in ’86-’87— froze damn near everyone here. Some of the old-timers said you could walk across the State of Kansas into Colorado just steppin’ on one dead animal after another. Monty Blevins, he’s been dead for years, he had 18,000 head of cattle and lost ’em all. Lost two cowboys too, froze to death sittin’ in the saddle up on Sand Creek Pass.”

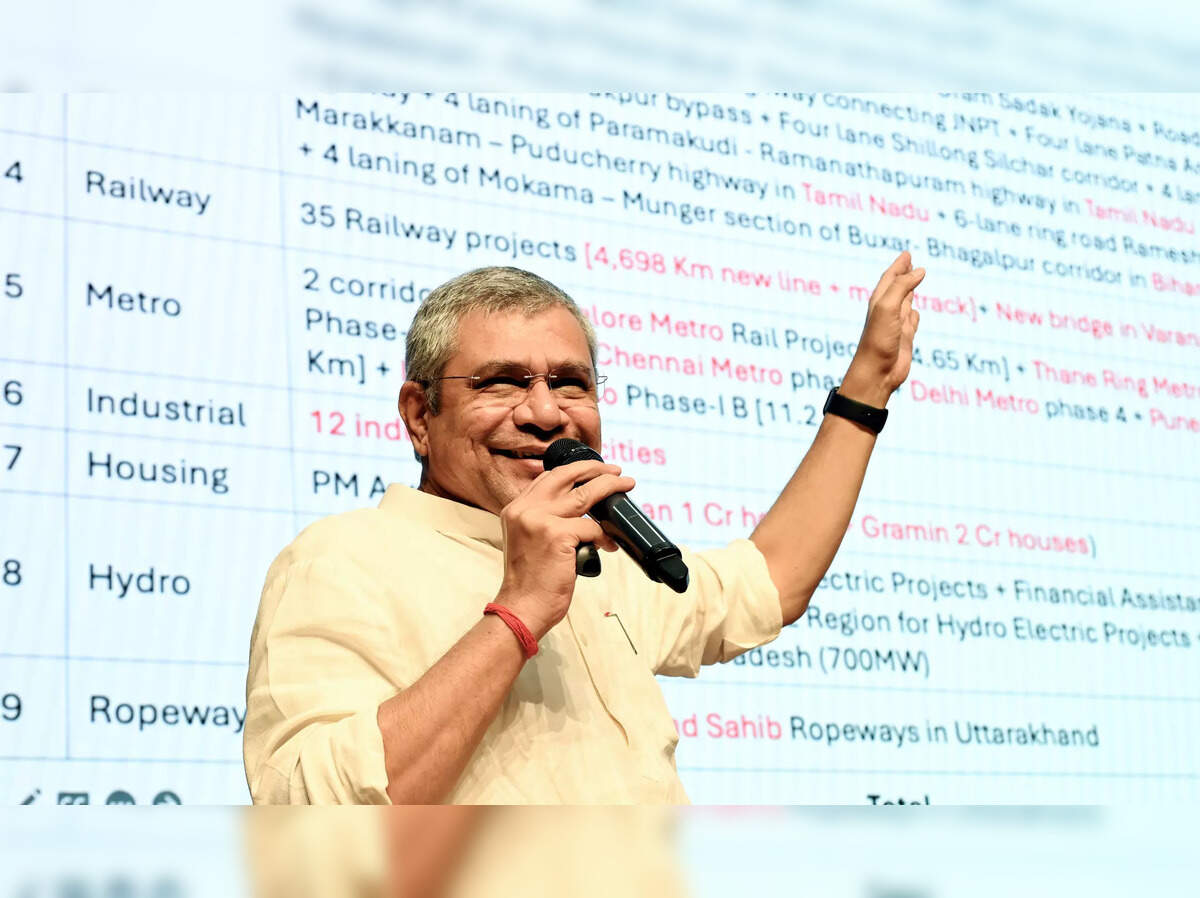

The Robert Redford expeditionary party rides through the town center of Telluride, Colorado.

I asked what he knew about Tom Horn, one of the most mysterious and fascinating characters in western history.

“Well, he was a bounty hunter, hired by them big cattle barons to get rid of rustlers.”

Horn moved in secret and alone. His past and true story to this day are, at best, shadowy. He died on the gallows in Cheyenne in 1903, accused of murdering a 14-year-old boy.

Did Roupe think he did?

“Don’t know … No one knows …”

I said goodbye to Larry Roupe and thanked him. It had been rewarding. He said, “Sure, lad, anytime.”

The free spirit thrives among the area’s newcomers as well. A mile or so out of town lives John Mionczynski. Riding toward his cabin, the first thing you can see is a wind charger, a crude wooden tower with a small windmill atop and a wire leading down to a 12-volt battery.

The cabin itself is designed for need, giving it a truly natural warmth. John built it himself—out of logs, dead standing timber, boards from an old highway snow fence, and abandoned machine parts—a snug home made of waste materials.

He is nestled there on ten acres with a stack of firewood for winter and goats for milk roaming nearby. No one can touch him. We were greeted by a tall, slender, dark young man. Later we munched a raw potato from his root cellar, opened a beer, and talked.

“I worry about this becoming fashionable,” John said. “People coming in from Rock Springs, where the big power plant is, or from California. I love it here. But if the flow gets too great, I’ll pick up and leave.”

Someone else came—a young, attractive, green-eyed woman from Kentucky. “What are you doing here?” I asked. “Living,” she said. It was said straight and simply. There is a return-to-the-land movement, and it is alive and well in Atlantic City.

Ghost Town Offered Cramped Quarters

South Pass City, our next stop, is another century-old tintype, this one restored by the State of Wyoming. It seemed as barren as a Salvador Dali landscape, except for the miniature town with its warped boardwalks. Could it be that so much history happened here? Why did everything seem so small—like dollhouses? Were rooms really that tiny and beds that narrow and stairs that tight?

Through South Pass, a 20-mile-wide niche in the Continental Divide, moved such figures as Jim Bridger, Dr. Marcus Whitman, Kit Carson, Jedediah Smith, and Broken Hand Fitzpatrick—as well as outlaws by the score.

Thousands of emigrants rolled through here in wagon trains between 1840 and 1869, when the transcontinental railroad was completed. In 1868 a gold rush began, and the population swelled from a few hundred to more than 2,000 overnight.

Here John Browning, inventor of the Browning automatic rifle, was an apprentice in a gun shop, and Buffalo Bill “cut his teeth with the pony express.” Here, too, lived Calamity Jane and Esther Morris, the first woman justice of the peace in the West.

By the mid-1870s the mines that had produced millions were played out, and the town was given over to outlaws. In 1896 it became a link in the chain of hideouts established by Butch Cassidy and the Wild Bunch.

We walked silently through the old general store, post office, jail, saloon. At the old bar, one could almost hear the faint calliope of voices, music, poker chips, breaking glass. Then the hotel, with hallways barely wide enough to walk through. And the jail cells: small, dark, claustrophobic—I couldn’t conceive of spending five minutes in one.

You May Also Like

Violence Begets Violence Among Outlaws

Among the jail’s former occupants, Kerry told us, was Jesse Ewing, a hardcase outlaw who had been clawed so badly by a grizzly bear that he was nicknamed the “Ugliest Man in South Pass,” and Isom Dart, a black rustler and horse trainer for outlaws.

Ewing didn’t take to sharing a cell with a black and forced Dart to kneel while he used his back as a table. Isom, it seems, consented because he feared he’d be lynched were he to abuse the white man. The score was settled later when a friend of Dart’s blew Ewing’s head off. And, in keeping with those violent times, Dart himself was shot from ambush by the mysterious Tom Horn as the black man stepped from his cabin near Browns Park.

South Pass City had truly one of the wildest reputations in the West, with its steady influx of miners, gamblers, thieves, Pinkerton men, cattlemen, and brawling railroad workers.

As I stood in the center of the main street, looking to the gray-brown hills beyond, I was lost in this memory—a memory of the rich, raucous innocence of the new frontier, of boardwalks and tents and snake-oil eagerness—an indomitable spirit. All quiet now, faded into a still freeze here in the sepia time of late afternoon. All an echo now, of a rich and vibrant part of our heritage.

South Pass City was for me, finally, a sad place.

We traveled now by four-wheel vehicle to our next horse and saddle station, Browns Park, Utah. It was about a 150-mile drive from South Pass City to the park via Rock Springs, Wyoming.

This is flat, wide range country with streams flowing from the high passes at the Continental Divide. October here is a gray streaked sky; a lovely time, the time just before the winter, with a stillness in the air. The calm before the storm.

Tomorrow the hunt will begin. To be sure, many people still hunt out of genuine need, to provide for the family. But they are almost lost in the vast army—from as far as California and the East—who come and kill for the sport. Too many will shoot anything that moves. D day. We hurry south toward the Utah border and Browns Park.

New Energy, New People

Rock Springs, Wyoming, speaks for itself: boomtown. Transmission lines and neon stretching out in the middle of a vast plain. Construction trailers and temporary housing painting a portrait of impermanence.

Nearby the 400-million-dollar Jim Bridger Power Plant is still under construction, and thick, low-sulfur coal seams lie beneath surrounding Sweetwater County. Production was 218,000 tons in 1970; it may reach 12 million tons by 1980. Chemical plants in the vicinity turn out more than half the nation’s soda ash for industry, and two new uranium mines are opening. Population has increased from 18,400 in 1970 to 40,000 today.

I wonder. In another century will someone come along and view Rock Springs with the same historical interest we had just given to South Pass City?

Perhaps no location on the Outlaw Trail has such a varied history as Browns Park, located on the Utah-Colorado border just south of the Wyoming line.

In 1825 the famous expedition of William H. Ashley and his fur trappers penetrated this 30-mile-long valley in bullboats along the Green River. In the 1830s Kit Carson traded here among the Ute and Shoshone Indians.

Outlaws used this isolated haven as early as 1860, when they began pilfering horses and cattle from the wagon trains streaming westward along the Oregon-Mormon Trail. Big-time rustling, however, came after the Civil War. Unemployed trail hands and other drifters raided the big herds of longhorns moving from Texas to fresher pastures in Wyoming and Montana. They often wintered the rustled cattle in Browns Park until they could be sold.

Until the turn of the century the only law in Browns Park was that of the fastest gun. The graves of men who died violently are scattered along the river. But most of the other markers, cabins, saloons, and hideouts are gone now.

We headed for the Allen ranch, one of four left in the Utah section of Browns Park. A cowboy had told us to “follow the road to the first left, then go down a long canyon … head out to the juniper, turn left again.” Needless to say, we got totally lost.

After many wrong turns and with the gas gauge nearing empty, we saw a single light, like some small island in a dark sea—the Allen ranch. We went in and met up with two more of our group who were enlisting late: Edward Abbey and Kim Whitesides.

Ed, an all-around western adventurer, doesn’t talk much about the West; he lives it. One suspects that beneath his calm, raw boned exterior there is a great rage about what’s happening to this part of the country. Kim Whitesides is an artist with a voice like a slowed-down phonograph. His movements are slow and his hand is sure.

They had arrived separately and were already ensconced with the Allen family in good talk by a fire, and eating the rancher snack-biscuits, jam, and coffee.

Marie Allen is the daughter of early settlers in the Browns Park valley, and the Allens’ home is a pioneer ranch house, simple, warm, and inviting. They are Mormons; with them you are welcome, you can share, no one is going to push you. But you are not going to push them either.

You sense in the Mormons an incredible strength that stems from persecution and survival, both in their struggle with the land and in the history of their religion.

Bassett Sisters a Sturdy Breed

Next morning we set out to explore Browns Park, riding west from the ranch. Kerry Boren grew up in the nearby town of Manila; he knows this area well. His grandfather, he says, used to sell and keep horses for Butch Cassidy when the outlaw rode through.

Kerry took us to meet Esther Campbell, a lively and untroubled 76-year-old woman who maintains a relic of a limestone building in her backyard as a museum. This was once the property of John Jarvie, who ran the valley’s first store and post office; he was murdered in 1909.

Esther told us about the famous Bassett sisters who lived at the opposite end of the park. Josie and Ann Bassett learned to ride, rope, and shoot alongside any man in the area. Ann, refined and well educated, grew up to become “Queen of the Cattle Rustlers.” Her sister, Josie, a girlfriend of Butch Cassidy, was more domestic, yet did her own fishing and hunting. The Bassett ranch became the social center of the valley.

Esther keeps artifacts from the past at the old Jarvie cabin ore buckets, tomahawks, arrowheads, and pictures of Josie, Queen Ann, and others. Outside she showed us a crossbar removed from the corral gate of the Bassett spread, from which enraged relatives and friends of a murdered man hanged one Jack Bennett in 1898.

One Outlaw Joined the Opposition

We crossed a wooden bridge that spans the Green River and pitched camp on a shallow bank. After dinner the fire simmered to a purple glow, the night chill surrounded us, and shadows of the park’s history came to life. Within a few miles, Kerry told us, stood the old cabin of Matt Warner, one of the Wild Bunch, among the last to survive (he ended his life as the town marshal of Price, Utah). Nearby was the crude rock-pile grave of a drifter named Indian Joe, who was knifed in a poker game.

Next morning we moved deeper into the park, riding on the cliffs that border the Green River about ten miles below the old Jarvie ranch. It was tough going, and one false move would have pitched horse and rider several hundred feet below to the river.

A long sweep through a grazing valley once used by outlaws and we were winding back to the east, passing below the foot of Diamond Mountain and Cassidy Point. Kerry told us that originally there had been a cabin on the point, concealed beneath an overhanging ledge but commanding a view of the park for miles in all directions. All that remains at the cabin site now is a large trench in which the men proposed to make a last stand if surrounded. It was supposedly here and at the Powder Springs hideout that Cassidy made plans for the “Train Robbers Syndicate,” including such Wild Bunch members as William Ellsworth (Elzy) Lay, Kid Curry, and the Sundance Kid. Between 1899 and 1901 they robbed three trains in Wyoming and Montana, though the safe of one express car yielded only $50.40.

We rode down into a flat area near the river, where we saw the remains of an old cabin and a springhouse. This, said Kerry, was old Doc Parsons’ place. Doc died in 1881 and is buried nearby. Matt Warner lived in the cabin for a while, as did Butch Cassidy, Elzy Lay, and other outlaws.

In 1972, just as valley residents expected the Utah Division of Wildlife Resources to raze the cabin, Kerry, Marie Allen, and others succeeded in getting it placed on the state register of historic sites. Other places probably won’t be so fortunate.

I looked back toward Diamond Mountain and the Parsons cabin, and wondered what would happen to the people who were left here. Much of this land is under a government jurisdiction that seems uninterested in memory or legends. Ranchers have been forced to sell under threats of condemnation.

Fifty Miles by Road, Ten Afoot

We rode back to the Allen ranch, where Bill Allen was waiting with instructions on how to get to Little Hole on the Green River, another historic outlaw hideout of the late 1800’s. Little Hole was also where we filmed the opening sequence of Jeremiah Johnson, so I had a certain nostalgia for the spot.

There were two routes: either fifty miles by road, or ten miles on foot over a pass. Kim Whitesides and I decided to hike it; the others, led by Abbey, would drive around with the supplies and horses.

It was getting close to 2:30, and the late autumn sun would die behind the mountains soon. A move in the wrong direction would lead us into a labyrinth of canyons and gulleys. Our apprehensions, however, soon gave way to the awesome beauty around us.

As we followed a dry creek bed through twisted piñons and huge rocks alive with orange lichens, it felt good to be footloose and unencumbered by horse and pack. I wondered how many people had taken this route. It seemed virginal, untrampled.

Night was coming hard as we sighted the river and dropped down to the Little Hole region. We had built an entire settlement from historic photographs for the film here: a thriving western town with a river landing, post office, saloon, and encampment. Thinking that it might serve neighboring Vernal and other communities well as a tourist attraction, or a reminder, or simply a point of interest, I had prevailed on the studio to leave it there. But the U. S. Bureau of Land Management, claiming it a nuisance and health hazard, had it torn down. It is now just another bend in the river.

Incredibly, Ed Abbey and the others arrived at Little Hole at the same moment. By the time we had forded the river, finished dinner, and settled down, the moon had come up, full and bright.

A beautiful morning, and a perfect place for an outlaw stronghold. A cabin survives here, that of Tom Crowley, who used to bootleg whiskey to the Indians. Built in 1869 with stolen railroad ties, it has seen many occupants over the past century. An outlaw named Mexican Charlie was shot here for cheating at cards; he lies buried a few yards away.

Crowley’s place now stands in danger of destruction through indifference and increasing development.

History Inundated by Progress

We headed for Vernal, Utah, where outlaws on the run often obtained fresh horses. The four-wheel drive took us along the edge of Flaming Gorge, where many cabins, homesteads, caves, and grave sites were drowned when the Green River was dammed to create this vast reservoir and recreation area.

In the distance the Colorado Plateau stretched across the horizon, lean and graceful, encompassing incredible space in perfect harmony with the sky. It rankled to imagine the plans for oil shale and other development that will certainly determine its fate.

Down along the parched, desolate Nine Mile Canyon we came across a pleasant stretch of green-again part of the old trail often used by the outlaws.

I stopped to talk to a leathery, squint-eyed rancher repairing a tractor in a field. I was unprepared for the hostility in his replies.

“How long have I been here? Too damn long.”

“It’s very beautiful,” I offered.

“Yeah? Well, you can have it. You want to take those cows out there off my hands, you got it. This is a hole—a hellhole. Ain’t nothin’ but dust and rocks and some starvin’ cows. Let me outta here and up to Minnesota. That’s the only place left where a man can make a livin’ farmin’ or ranchin’.”

“What’s wrong around here?” I asked.

“No one cares about it. No water. No one has the money to develop it for ranchin’. All anybody’s interested in is buyin’ up mineral rights for power development and real estate. We’re gettin’ starved out.”

As we rode on, I thought that this was the real plight of the ranchers in the area. They often don’t see the beauty of their surroundings because they feel economically blocked by the same surroundings and therefore resent them.

Rugged Canyonlands Discouraged Lawmen

At Green River we met A.C. Ekker, who runs an outfitting and guide service called Outlaw Trails. A.C. is a hardworking, hard-riding ex-rodeo cowboy who suggests, more than anyone I’ve come across, the verve, strength, and enterprising spirit of the early settlers. In a shrinking society of worn leather and tired spirits, he stands out.

He welcomed us with the friendly but wary eye of one who suspects a tenderfoot and led us to the Ekker homestead, some eighty miles south. There, in a stucco ranch house, we met his father, Arthur, who has ranched the Roost country for almost 40 years. At 65, Arthur is crusty but energetic, with eyes almost hidden in the folds of a squint. As he told us of this region, he spoke in bursts of exclamations, as if he had dozed off between thoughts and didn’t want to get caught at it.

Robbers Roost was the last of the three big way stations along the Outlaw Trail. Unlike the others, it was not a secluded valley, but a dry, rugged, thirty-mile-wide plateau sliced by formidable canyons, with lookout points on all sides. This was desolate country. Isolated from settlements by miles of desert, it was almost inaccessible except to the few who knew the route. The outlaws knew where vital springs were and could survive there.

“Yep, ol’ Butch was the best,” A.C. said as he pried away at his mouth with a tooth pick. “Plenty popular in these parts. Him and Matt Warner and the McCartys used to bring in stolen horses from western Utah. No one could follow ’em—too tough. When the coast was clear, they’d move ’em on to Colorado.”

“They used to live in sandstone caves or in crude cabins of twisted cedar,” Kerry Boren chimed in.

Butch was always leaving something for the ranchers, taking care of them for their help and always keeping his word. In unspoken agreement, the ranchers never talked about seeing him. The rule of word—if you broke it, then what? “Well,” said A.C., “then someone would show up and put a bullet in you to square the deal.”

It snowed that night. In the morning we shook several inches from our sleeping bags and headed out into a cold mist for the outlaw stronghold on the edge of Roost Flats. As we rode along on a carpet of fresh snow, our bones as brittle as ice shards, the gray oppressive stillness lifted. Now the air was blue and frosty with white everywhere—a true white, with color in it. It was revitalizing, like tasting mint leaf.

A. C. spotted a band of range horses, and we took out after them as if there were no other task and no tomorrow. The leader of the band was a beautiful buckskin stallion with thick neck and a tail that reached the ground. He led the others for three miles just a step ahead of us until we caught up and raced alongside. The stallion’s eyes were alert and wild. Yet I think he sensed, amidst the threat, the feeling of play to all this. After a good look we let them go, and they ran away to the south, led by this untamed Pegasus. I couldn’t deny a feeling of envy at the sight.

It was about six miles to the Roost and down into a small cut where Butch Cassidy’s hideout was.

The original corral is still here, and we put our horses in it while we ate. Afterward we circled the Roost looking at the remnants of an old outlaw society—a stone chimney, caves, and carvings.

Cassidy’s camp became the center of all activity in the region. Even people who were not considered outlaws came here to play poker and race their horses with the sporty members of the gang. It is said that Butch was the most amiable of all the western outlaws, fun loving and a gentleman with women. There is no evidence that he ever killed anyone, unless it was at his legendary final stand in 1909 at San Vicente, Bolivia.

Several women lived at the camp; they often shopped for supplies and purchased ominously large amounts of ammunition in the nearby towns of Price and Green River. Maude Davis (wife of Elzy Lay) was there, and the mysterious, beautiful Etta Place girlfriend of the Sundance Kid-was thought to be among them.

We had to jog along at a good clip to get to camp before dark. We had traveled close to twenty miles for the day. Men used to ride like this most of the time, harder and longer, over even rougher terrain, because they had to.

Did Arthur Ekker remember those times? “Sure, when I was a kid, a horse was the only way you could get around. Steal a horse and you was a marked man-like takin’ a man’s gun away from him. But you could find wild herds all over these flats. Hardly any left now.”

Cassidy’s Fate Still Argued

We warmed frozen appendages by the fire, beat frozen boots against rocks, drank herb tea, and listened to Arthur reminisce.

On rustling: “Used to change the old brand of a cow with a hot iron. Some of the rustlers came up from Texas—it was a fast way to get into the cattle business.”

On Butch Cassidy: “Lots of folks around these parts believe he never died in Bolivia. Fella named Hanks from over to Hanksville, who used to take supplies out here to the Roost, claimed he seen Butch in the ’20’s.”

On his youth: “First time I took this trail I was 7 or 8. In the old days people were tougher. Why, over in Hanksville they had to ride 50 miles for a doctor. By the time you got there, you was either dead or well. Undertaker did a lot of business.”

He also spoke of the future: “Robbers Roost won’t change much,” he said. “You can’t irrigate it, and there’s no coal to dig out. There’ll be livestock here as always. But the national parks are movin’ in on a lot of the ranches, and I suppose much of the land will be used for recreation.”

We headed west out of the Roost, down across Dirty Devil River past Hanksville and south to Lake Powell, created by the damming of the Colorado in 1963. The next couple of days we traveled by boat—still on the Outlaw Trail, but here its remnants were submerged. At the lower end of the lake near Page, Arizona, the dependable A. C. Ekker and one of his ranch hands were waiting for us.

Butch Cassidy Lives On in Memory

It seemed fitting that we finish our trail ride at the home in which Butch Cassidy grew up, and celebrate the journey’s end with Butch’s sister, Lula Betenson, in her 90’s now and living in the nearby town of Circleville, Utah. This would complete our story.

Lula Betenson and I had first met in 1968 when she visited the film set of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, in which I played Sundance. She struck me then as an unusual person—spry, witty, strong-willed, and with a gentle feminine spirit. Lula was one of 13 children and only a baby when Butch left home.

Nowadays she sits in her parlor wearing a pink sweater over her shoulders. Always energetic, she jumps up from time to time to get someone coffee or whatever, refusing to let anyone do anything.

She says she has just been to visit 79-year-old Marvel Murdock, the daughter of Elzy Lay, now living in Heber City, Utah. Lula asks why we all move around so much, wants to know what the rush is, and hopes we’re getting something out of it.

Later, she led us all to the original homestead and the cabin she and Butch grew up in. It was late afternoon and a fall breeze was blowing leaves around the cabin. Lula and I walked along together through the old house and around the land. She talked of losing sight in her right eye and starting to lose it in the other. She took hold of my arm and looked me straight on.

“I don’t mind dying,” she said. “I’m just afraid it won’t be soon enough. I’m fightin’ the melancholy. Don’t like goodbyes … can’t stand ’em…. Never used to bother me.”

She seemed cameo pretty standing there amid the poplars—with a youthful countenance and eyes that seem unfairly framed in the wrinkles of age.

The house is old. Gray-splintered sagging wood. The window frames are bleached. The rooms are small, as in all the buildings of this kind we have visited. Burglars have looted the original furnishings. Out back are the corrals—the original ones—tired and tilted against a background of burnt-yellow and gray hill.

It’s all that’s left. Lula and the corrals and the hills. There’s no more.