Get the Popular Science daily newsletter💡

Breakthroughs, discoveries, and DIY tips sent every weekday.

For being the world’s oldest known synthetic pigment, the original recipes for Egyptian blue remain a mystery. The approximately 5,000-year-old dye wasn’t a single color, but instead encompassed a range of hues, from deep blues to duller grays and greens. Artisans first crafted Egyptian blue during the Fourth Dynasty (roughly 2613 to 2494 BCE) from recipes reliant on calcium-copper silicate. These techniques were later adopted by Romans in lieu of more expensive materials like lapis lazuli and turquoise. But the additional ingredient lists were lost to history by the time of the Renaissance.

This is particularly frustrating not just for preservation efforts, but because of Egyptian blue’s unique biological, magnetic, and optical properties. Unlike other pigments, the Egyptian blue emits near-infrared light wavelengths that are unseen by the human eye, making it a promising tool for anticounterfeiting efforts, fingerprinting, and even high-temperature superconductors. But after studying ancient materials and manufacturing methods, a team led by Washington State University (WSU) researchers in collaboration with the Smithsonian’s Conservation Institute and the Carnegie Museum of Natural History have created not just one historically accurate Egyptian blue, but 12 of them.

While the results are detailed in a study published in npj Heritage Science, first author and WSU materials engineer John McCloy said the project began as something much more casual.

“It started out just as something that was fun to do because they asked us to produce some materials to put on display at the museum, but there’s a lot of interest in the material,” he said in a statement.

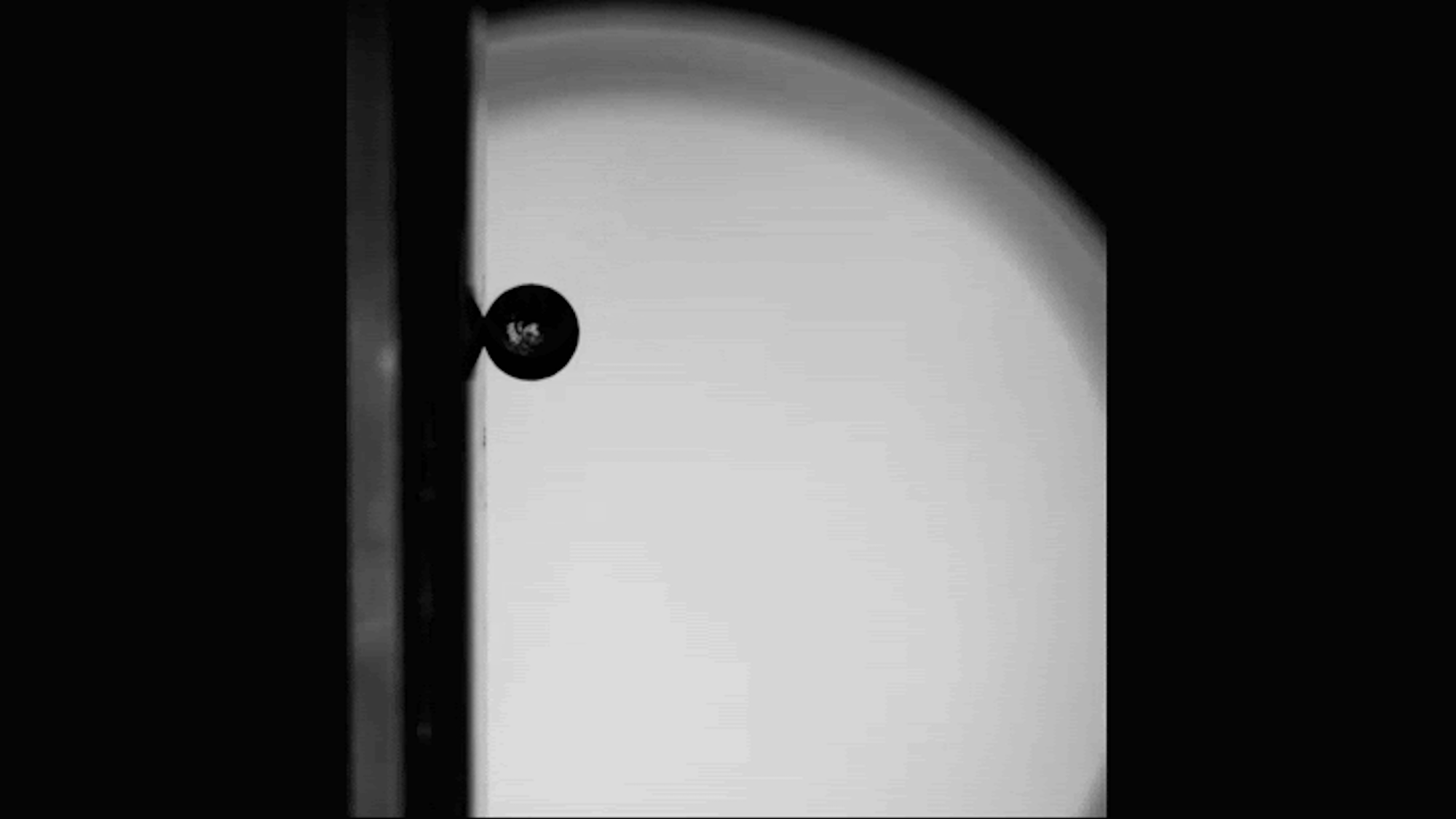

McCloy and colleagues first consulted both a mineralogist and an Egyptologist to create a list of potential materials to develop the pigments, including mixtures of calcium, copper, silicon dioxide, and sodium carbonate. From there, they varied the ingredient proportions before heating them anywhere from 1 to 11 hours at around 1,832 degrees Fahrenheit—temperatures achievable by ancient Egyptian artisans. Once the mixtures cooled at varying rates, the team analyzed each final result using techniques including X-ray diffraction, electron beam X-ray microanalysis, and X-ray nano-computed tomography. Finally, they compared these samples to a pair of Egyptian artifacts including a piece of cartonnage—a papier-mâché-like material used for items like funerary masks.

“One of the things that we saw was that with just small differences in the process, you got very different results,” McCloy said.

For example, cooling rates played an important role in influencing the end color. Slower cooling times offered deeper blues, while quicker cooling produced pale gray and green mixtures. Despite this, the bluest of the 12 variants only required about 50 percent of their ingredients to exhibit blue hues. McCloy’s team also confirmed that cuprorivaite—the naturally occurring mineral equivalent to Egyptian blue—remains the primary color influence in each hue. Despite the presence of other components, Egyptian blue appears as a uniform color after the cuprorivaite becomes encased in colorless particles such as silicate during the heating process.

“It doesn’t matter what the rest of it is, which was really quite surprising to us. You can see that every single pigment particle has a bunch of stuff in it—it’s not uniform by any means,” he added.

The results go beyond establishing Egyptian blue recipes that largely mirror ancient examples. McCloy and colleagues hope that these initial 12 variants will be used in conservation work to restore historic relics as accurately and vividly as possible.

More deals, reviews, and buying guides

The PopSci team has tested hundreds of products and spent thousands of hours trying to find the best gear and gadgets you can buy.