Now Reading: The geography of Trump deportations: DOJ is seeking friendly courtrooms

-

01

The geography of Trump deportations: DOJ is seeking friendly courtrooms

The geography of Trump deportations: DOJ is seeking friendly courtrooms

A home security camera captured a defining image of President Donald Trump’s mass deportation efforts.

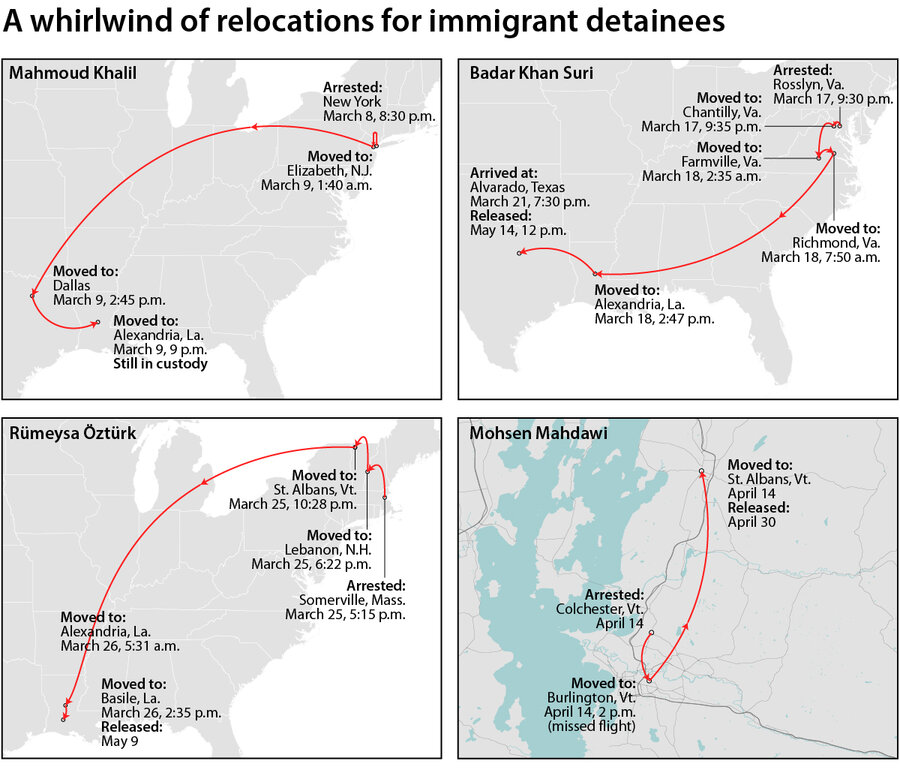

On March 25, masked and plainclothes immigration officers stopped Rümeysa Öztürk on the street in Somerville, Massachusetts; handcuffed her; and placed her in an unmarked vehicle. A roughly one-minute-long video captured it all.

What happened next, out of the public eye, also exemplifies the government’s aggressive approach to immigration enforcement. Less than 24 hours after her arrest, the Tufts University doctoral student had been whisked 1,500 miles across the United States to a detention center in Louisiana. In between, she had been held at three facilities in three different states.

Why We Wrote This

To enact President Donald Trump’s deportation goals, the Department of Justice is rapidly transferring detainees to areas seen as friendly jurisdictions. A growing number of courts are urging more restraint.

This kind of rapid relocation of immigrant detainees has been common in recent months. International students like Ms. Öztürk, in the country lawfully but deemed deportable by the secretary of state, have struggled to contest their detention. The government has taken a similar approach with migrants it says are Venezuelan gang members. The White House is trying to use an 18th-century wartime law to deport them without trial.

SOURCE:

Federal court records

|

Henry Gass and Jacob Turcotte/Staff

The Trump administration has said these quick-fire transfers are necessary for security reasons. In immigration cases, the practice is neither unlawful nor unprecedented, but it has raised due process concerns, particularly in federal courts.

The U.S. Supreme Court recently debated whether lone federal judges have the power to pause White House policy around the country. Yet some of those judges have been dealing with the reality of a more decentralized, justice-by-geography system. The Trump administration has been relocating immigrant detainees at a greater rate than past administrations, experts say, and White House officials have also questioned fundamental rights to challenge these actions.

Tufts University student Rümeysa Öztürk, of Turkey, is seen during a press conference at Boston Logan International Airport after she was released on a judge’s order after spending over six weeks in an immigration detention center in Louisiana, May 10, 2025.

Rapid transfers

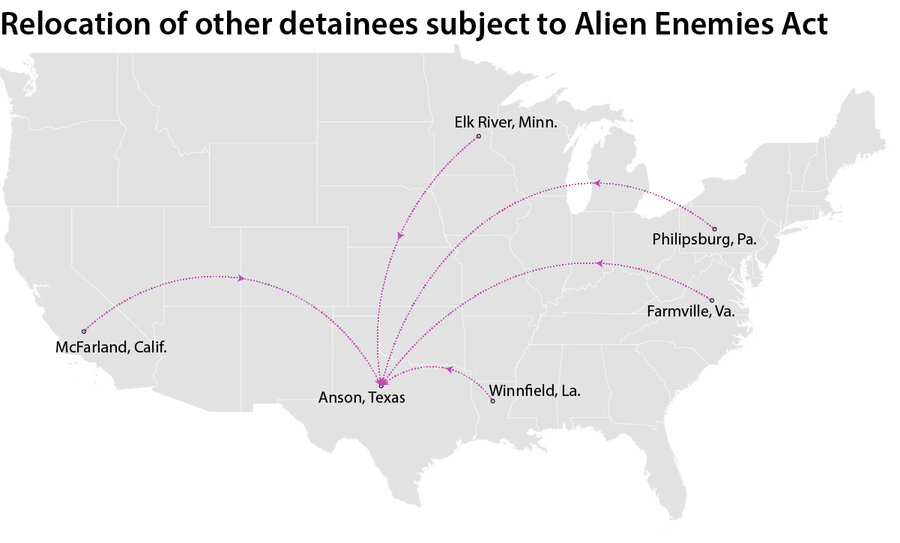

Litigation concerning the Alien Enemies Act of 1798 has been the most active stage for this legal debate. The Trump administration has been using the law to try and deport alleged members of Tren de Aragua – a Venezuelan gang it has declared a foreign terrorist organization – to a prison in El Salvador.

On April 7, the Supreme Court ruled unanimously that challenges to the removals must be brought via habeas corpus, a longstanding right to challenge one’s detention, in “the district of confinement.”

Trump administration officials have suggested they might suspend habeas corpus, which is enshrined in the U.S. Constitution to protect people from being unlawfully detained. This week, Secretary of Homeland Security Kristi Noem erroneously described the right as “a constitutional right that the president has to be able to remove people from this country.”

In the past month, federal courts across the U.S. have temporarily barred the Trump administration from removing unauthorized immigrants under the act. As a result, the government has been flying detainees into one jurisdiction that hasn’t: the Northern District of Texas. From there, immigration agents initiated expedited removal proceedings. These actions prompted a rebuke from the Supreme Court last week as the justices paused Alien Enemies Act deportations in that district.

SOURCE:

Federal court records

|

Henry Gass and Jacob Turcotte/Staff

The government has broad discretion to transfer detainees in removal proceedings. Rapid transfers are even more necessary when you’re dealing with alleged members of Tren de Aragua, which began as a prison gang, the government says.

“Unsurprisingly,” the Trump administration wrote in a memo to the Supreme Court, “they have proven to be especially dangerous to maintain in prolonged detention.”

Immigration advocates are unsure exactly how many Venezuelans have been transferred to detention centers in the district. According to a Monitor review of court records, dozens were moved to the Bluebonnet Detention Center in Anson, Texas, in mid-April before being told they would be removed within a day.

When asked by the Monitor about transfers to Bluebonnet, an ICE spokesperson replied by email that “U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement does not provide population or capacity numbers due to operational and security concerns.” He added, “Additionally, the numbers fluctuate quite often as detainees are being processed, transferred to other detention centers, or being removed from the country.”

In one case, the government transferred a 22-year-old Venezuelan from California to Bluebonnet on April 14, a week after the initial Supreme Court ruling. A day later, the government moved a Venezuelan from western Pennsylvania to Bluebonnet while a federal judge issued an order temporarily pausing such transfers from her district.

Statistics show that judges in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, which covers Texas and Louisiana, more reliably favor those seeking to deny habeas claims and deport immigrants.

“Attorneys see a statistical correlation between the circuit where a case is tried and the outcome,” says Seth Chandler, a professor at the University of Houston Law Center.

That said, a federal judge in southern Texas has temporarily paused deportations from his district under the Alien Enemies Act. The judge in western Pennsylvania, meanwhile, is allowing them to proceed with strict due process requirements.

Access to legal representation

International students like Ms. Öztürk experienced even more of a whirlwind tour of immigrant detention facilities.

In the 12 hours after her arrest, the government moved her from Massachusetts to New Hampshire, and then to Vermont before her flight to Louisiana. Mahmoud Khalil, Mohsen Mahdawi, and Badar Khan Suri were all also deemed deportable by the secretary of state. They all had similar experiences after their arrests, according to court records.

While family members and attorneys tried to locate them, immigration officials shuttled the students between two or three local detention facilities before flying two of them to Louisiana. In the case of Mr. Mahdawi, a flight out of state left before he arrived at the airport. In the case of Mr. Suri, the government drove him to north Texas after three days in Louisiana.

The government gave various reasons for the relocations, according to court records, including a lack of bed space and bedbugs.

Three of the students have since been released pending a final ruling in their cases. Their lawyers successfully claimed they had filed habeas petitions in the hours between their arrest and their arrival in Louisiana. In the cases of Ms. Öztürk and Mr. Mahdawi, judges said they had significant constitutional concerns about their treatment.

Federal judges in Vermont and Virginia will continue hearing the three students’ habeas claims. Immigration court proceedings are likely to continue simultaneously in those states. Mr. Khalil is still detained in Louisiana while a federal judge in New Jersey determines if he has jurisdiction over the Columbia graduate and green-card holder’s habeas claim. An immigration judge has ruled that he can be deported.

The other students’ releases and continued court fights would not have been possible with good legal representation, however. Most individuals subject to deportation have no lawyer.

“There’s always a big rush to get a habeas filed because you know the government is going to ship your client out,” says Margaret Stock, an immigration lawyer based in Alaska.

She would know. In the late 1990s, Ms. Stock represented a naturalized U.S. citizen whom the government tried to deport to Yemen. Among the challenges in the case: The government sent her client to a detention center in Southern California, over 2,000 miles away.

Ms. Stock successfully argued that the case had to be heard in a friendlier jurisdiction: her client’s home city in Alaska.