Now Reading: These are first deep-space images from the Vera Rubin Observatory

-

01

These are first deep-space images from the Vera Rubin Observatory

These are first deep-space images from the Vera Rubin Observatory

Perched high in the foothills of Chile’s Andes mountains, a revolutionary new space telescope has just taken its first pictures of the cosmos—and they’re spectacular.

Astronomers are excited about the first test images released today from the Vera C. Rubin Observatory, which show the universe in unprecedented detail, from violent cosmic collisions to faraway nebulas.

“It’s really a great instrument. Its depth and large field of view will allow us to take really nice images of stars, especially faint ones,” says Christian Aganze, a galactic archeologist at Stanford University who will use the observatory’s data to study the formation and evolution of the Milky Way. “We are truly entering a new era.”

The observatory has a few key components: A giant telescope, called the Simonyi Survey Telescope, is connected to the world’s largest and highest resolution digital camera. Rubin’s 27-foot primary mirror, paired with a mind-boggling 3,200-megapixel camera, will repeatedly take 30-second exposure images of vast swaths of the sky with unrivaled speed and detail. Each image will cover an area of sky as big as 40 full moons.

(The 4 biggest space mysteries the new observatory could solve)

The observatory’s Simonyi Survey Telescope, shown at night on May 30, 2025, is attached to a massive 3,200-megapixel camera.

Photograph by Tomás Munita, National Geographic

Every three nights for the next 10 years, Rubin will produce a new, ultra-high-definition map of the entire visible southern sky. With this much coverage, scientists hope to create an updated and detailed “movie” they can use to view how the cosmos changes over time.

“Since we take images of the night sky so quickly and so often, we’ll detect millions of changing objects literally every night. We also will combine those images to be able to see incredibly dim galaxies and stars, including galaxies that are billions of light years away,” said Aaron Roodman, program lead for the LSST Camera at Rubin Observatory and Deputy Director for the observatory’s construction, at a press conference in early June.

“It has been incredibly exciting to see the Rubin observatory begin to take images. It will enable us to explore galaxies, stars in the Milky Way, objects in the solar system—all in a truly new way.”

Here is another small section of the Virgo Cluster, representing just two percent of the telescope’s full field of view. It shows two prominent spiral galaxies (lower right), three merging galaxies (upper right), several groups of distant galaxies, many stars in the Milky Way and more.

Image by NSF-DOE Vera C. Rubin Observatory

Galaxies as far as the eye can see

The first set of images taken with Rubin’s specially-designed digital camera unveils the universe in startling detail. Researchers combined seven hours of observations into a single image which captures the ancient light cast out by the Lagoon Nebula and the Trifid Nebula. These vast clouds of interstellar gas and dust are 4,350 light-years away and 4,000 light-years away from Earth, respectively.

Two other photos show the telescope’s view of the Virgo Cluster, a mix of nearly 2,000 elliptical and spiral galaxies. Bright stars from our own cosmic neighborhood shine amongst sprawling systems of stars, gas, and dust held together by gravity. Each of the scattered pin-prick dots in the background represents a distant galaxy.

Observation Specialist Lukas Eisert at the Control Room of Vera Rubin Observatory, Chile. May 30, 2025.

Photograph by Tomás Munita, National Geographic

William O’Mullane, deputy project manager specializing in software, looking at images shot at Vera Rubin Observatory, Chile. May 31, 2025.

Photograph by Tomás Munita, National Geographic

Rubin’s images of the Virgo Cluster also show the chaotic jumble of merging galaxies—a process that plays a crucial role in galaxy evolution.

(Here are the four biggest mysteries the Vera Rubin Observatory could solve.)

“The Virgo cluster images are breathtaking,” Aganze says.“The level of detail, from the large-scale merging galaxies to details in the spiral structure of individual galaxies, more distant galaxies in the background, foreground Milky Way stars, all in one image, is transformative!”

You May Also Like

The first images shown to the public, Roodman added, “provide just a taste of Rubin’s discovery power.”

For the next decade, Rubin will capture millions of astronomical objects each day—or more than 100 every second. The first images include about 10 million galaxies and counting. Ultimately, it’s expected to discover about 17 billion stars and 20 billion galaxies that we’ve never seen before.

In this immense image, the Vera C. Rubin Observatory offers a brand new view of the Trifid Nebula and the Lagoon Nebula. The image demonstrates the observatory’s unique ability to take lots of big images in a very short time. It combines 678 exposures taken in just 7.2 hours of observing time and was composed from about two trillion pixels of data in total.

Image by NSF-DOE Vera C. Rubin Observatory

In search of dark matter

The concept for the project was conceived roughly 30 years ago to maximize the study of open questions in astronomy with cutting-edge instrumentation. Construction began in 2014 in Chile’s Cerro Pachón, at an altitude of 8,900 feet. Originally named the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope, it was renamed in 2019 in honor of the American astronomer Vera C. Rubin, whose work provided the first observational evidence of dark matter.

When the observatory begins science operations in earnest later in 2025, its instruments will yield a deluge of astronomical data that will be too overwhelming to process manually. (Each night, the observatory will generate around 20 terabytes of data.) So computer algorithms will sift through the large volumes of data, helping researchers flag any patterns or rare events in a particular patch of sky over time. Researchers also invite the public to explore the cosmos through the eyes of Rubin by downloading the SkyViewer app.

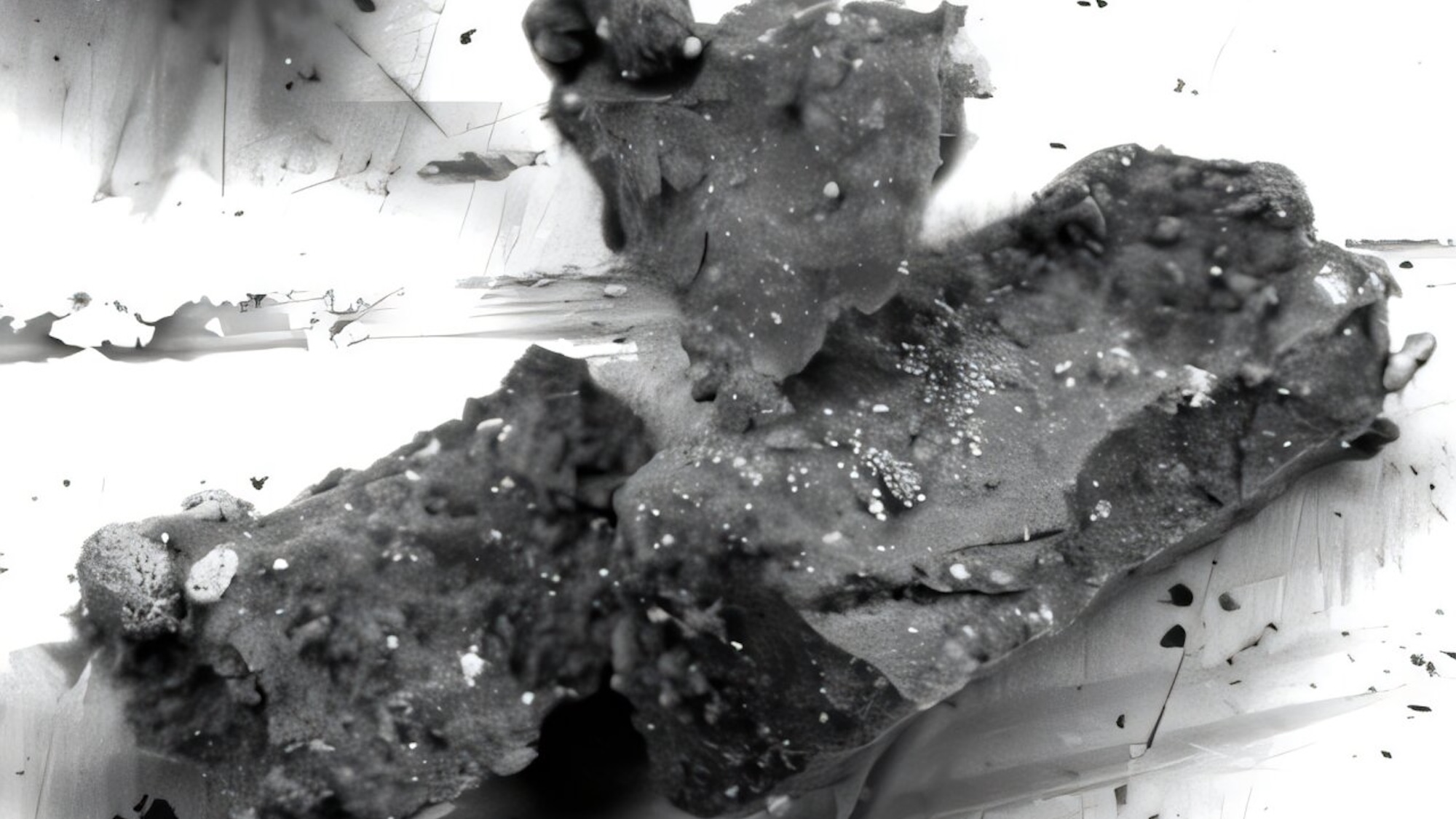

Astronomers expect high-quality observations taken with the telescope will help map out the structure of the universe, find comets and potentially hazardous asteroids in our solar system, and detect exploding stars and black holes in distant galaxies. Within the preview data, researchers have already found 2,104 never-before-seen asteroids in our solar system, including seven close enough to Earth to merit tracking but that pose no threat to our planet. (For comparison, all other observatories combined spot about 20,000 asteroids each year.)

Observatories on the ground and in space discover around 20,000 new asteroids each year. Rubin found 2,104 new asteroids photobombing its preliminary sky surveys and is expected to turn up millions more in its first two years of operation.

NSF–DOE Vera C. Rubin Observatory

The observatory will also examine the optical counterparts of gravitational wave events—ripples in the fabric of space caused by some of the most energetic processes in the cosmos. By studying these events, astronomers hope to uncover the secrets of the invisible forces that shape the universe like dark matter and dark energy.

“Those first few images really show the results of those 10 years of really hard and meticulous work that the whole team has put into it, ranging from designing, simulating, to assembling, characterizing and calibrating every single part of the observatory, telescope, camera, the data pipeline, everything was really done very meticulously,” said Sandrine Thomas, deputy director of Rubin Observatory and the observatory’s telescope and site scientist, at the June press conference.

“I really feel privileged to have worked with such a talented and dedicated multinational team,” Thomas added. “It’s really impressive.”

The Vera Rubin Observatory lit by a patch of light at sunrise.

Photograph by Tomás Munita, National Geographic

Editor’s note: This story was updated on June 23, 2025, to include a video and additional information released by the Vera C. Rubin Observatory.