Now Reading: These glowing seas have baffled sailors for centuries. Science may finally have answers.

-

01

These glowing seas have baffled sailors for centuries. Science may finally have answers.

These glowing seas have baffled sailors for centuries. Science may finally have answers.

“It looked as if we were sailing over a boundless plain of snow, or a sea of quicksilver,” writes Captain Kempthorne in his ship’s log.

Sailing a ship called Moozuffer through the Arabian Sea in January 1849, he witnessed something so rare that there are under 400 known records in 400 years and just one photo.

This ghostly phenomenon, called milky seas, has puzzled sailors and scientists for centuries.

After delving into centuries of ship logs like Kempthorne’s, eyewitness accounts, newspapers, and satellite imagery, Justin Hudson, PhD candidate at Colorado State University (CSU) and Steven Miller, an atmospheric scientist also at CSU, have published the world’s largest database of milky sea observations in the journal Earth and Space Science.

In it, they write that “throughout history, this topic has teetered on the edge between myth and scientific knowledge.”

But now their database could help to illuminate the centuries-long mystery.

A sample taken from a milky seas incident showed the presence of bacteria called Vibrio harveyi, which scientists think could be responsible for this glow.

Photograph by Dr. Steve Haddock, Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute

Rare bioluminescence

Milky seas are a rare form of bioluminescence: the light they emit is thought to come from bacteria.

Witnesses have described them as “the most fantastical thing they’ve ever observed,” Hudson says. They recall night-time seas turning to “thick milk or cream” and glowing “as though green neon lights were alight just under the surface of the sea.”

According to these eyewitness accounts, it can cause the whole surface of the ocean to shine for months at a time, bright enough to be seen from space. In daylight or moonlight, it vanishes.

In the novel 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, Jules Verne suggests this “lactified” ocean is caused by a “diminutive glowworm that’s colorless and gelatinous in appearance, as thick as a strand of hair, and no longer than one-fifth of a millimeter.”

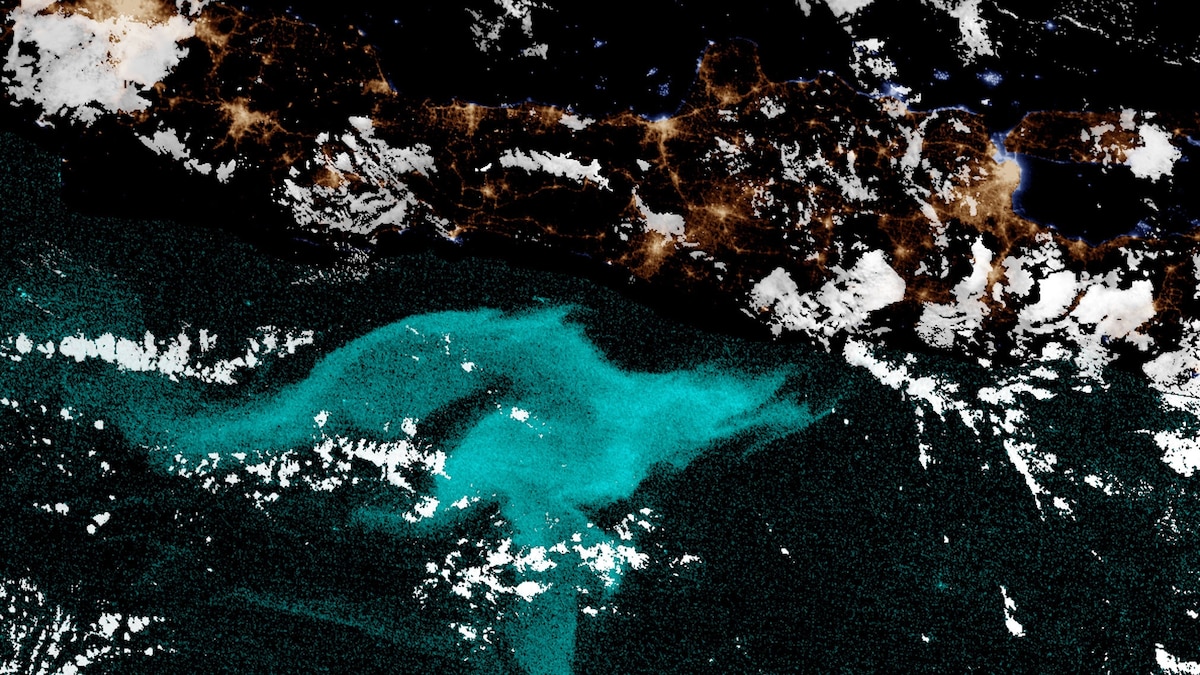

These NOAA satellite images, taken just two weeks apart in 2019 show an outbreak of bioluminescence in the seas just south of Java, Indonesia.

A research vessel that happened upon this phenomenon in 1985 collected water samples that contained a bacteria called Vibrio harveyi, which they hypothesized might be the source of the glow.

Like other bacterial bioluminescence, milky seas have a steady, even gleam “like the glow-in-the-dark plastic stars you can buy your kids,” according to a 1980 U.S. Navy sighting.

Accounts indicate that this glow is different from the transient sparkles that occur when plankton create bioluminescence, but the two can happen together.

Sailors in 1974 noted that “bright speckles of marine bioluminescence continued to appear in the water” as they sailed through a milky sea.

Among those who witness milky seas, they tend to report the ocean as appearing strangely calm. One captain describes how the unbroken waters “seemed so dense and solid” that his ship looked like “she was forcing her way through molten lead.”

This might be an optical illusion, or there could be some truth in it.

The research vessel that sampled a milky sea in 1985 found bioluminescent bacteria and a type of algae that “emits this mucus that calms the ocean’s surface,” Hudson says. This could account for the eerily flat seas.

How the database was compiled

People without scientific training “capture the information completely differently,” says Abigail McQuatters-Gollop a plankton ecologist at University of Plymouth in England, who wasn’t involved in the study. “They never thought it would be used for any ecological study.”

You May Also Like

Some descriptions found in old documents are too matter-of-fact and vague to know if they’re useful. Does ‘white water’ indicate a milky sea or rough currents?

“I think they did the best job they could do with the kind of data they had available…400 samples over 400 years is really not that much,” says McQuatters-Gollop. “But I was just intrigued by the whole thing.”

Hudson spent around nine months combing through records. Although the descriptions were taken by mariners, this qualitative data is valuable for scientists like the team at CSU. They can pinpoint times and locations that allow scientists to know where to look for more clues.

Their rarity makes studying these events almost impossible. Scientists can’t “have a boat permanently sit out there and hope and pray and wait,” Hudson says.

The only known photograph was taken by a private yacht sailing just south of Indonesia in 2019. The crew only realized what they’d seen after reading Miller’s 2021 Scientific Reports paper.

“There’s so much luck involved in witnessing this,” McQuatters-Gollop says.

New science emerges from old records

These events can span enormous distances, scientists have found.

“Milky seas can exceed [over 38,000 square miles],” Hudson says—that’s larger than the state of Indiana—“and last for up to months at a time.”

The new database suggests they typically cover around 3,800 square miles, although the data might be skewed because larger milky seas are more noticeable for both satellites and humans. “The bigger the event, the more likely [people] are to sail to it,” he says.

This new database shows that milky seas occur primarily in the Northwest Indian Ocean and in the Maritime Continent—a tropical region between the Indian and Pacific Oceans.

The study authors also learned that global climate patterns may play a role in their formation.

In summer, “following a La Niña there are more milky sea events than expected,” Hudson says. In winter, more occur at the peak of the positive Indian Ocean Dipole—when the alternating temperatures on either side of the Indian Ocean are warmer in the west.

They may be linked to stronger monsoons. These can cause upwellings, which bring nutrient-rich waters up from the deep, resulting in “an explosion” in the food chain, he says.

By revealing patterns among the complex interactions between these phenomena, this database could help researchers predict and even sample milky seas.

For now, milky seas remain enigmatic. “We don’t even know enough about them to know how important they are,” Hudson says.

Glimpsing the ghostly spectacle more often might even indicate poor ocean health. “The bacteria we suspect is causing milky seas is a known pest species that can kill off fish,” Hudson says.

If this is the case, fisheries and economies around the world could suffer if these events increase. Says Hudson: “The ocean is giving a very visible warning sign.”