Now Reading: Was Cyrus the Great really a tolerant conqueror?

-

01

Was Cyrus the Great really a tolerant conqueror?

Was Cyrus the Great really a tolerant conqueror?

The Achaemenid kings of Persia ruled between the sixth and fourth centuries B.C., but much of what we know about them today comes from Greek rather than Persian sources. The various Greek authors who wrote about the Persians tended to depict them as decadent and weak-willed, ruled by a series of self-styled great kings. Persian culture was often contrasted with the austerity of Athens and Sparta. The stories of Persian kings that have filtered down through Greek works of philosophy, history, and plays mix firsthand observations with a large dose of fiction and fantasy. It should be remembered that the Greeks saw the might of Persia as a huge threat. For half a century they were engaged in the Greco-Persian wars (499-449 B.C.), fighting to keep that threat at bay, and this enmity shaped how they framed their accounts. The Achaemenid kings were usually portrayed as exhibiting the most ignoble vices: being arrogant and cruel, lazy and weak-willed, lovers of luxury, and easily seduced by spies in the harem. The Greeks painted Persian kings as stereotypical barbarian rulers of a foreign world dominated by violence and cruelty.

There is, however, one exception: Cyrus II, known as Cyrus the Great. In general, the Greek sources present a very different story of his reign, which saw the creation of the Achaemenid Persian Empire, a vast dominion stretching from Asia Minor to the Indus River Valley, the largest empire known at the time. Through a series of brilliant military campaigns, Cyrus conquered all the great states of the Near East (except Egypt) in just over 10 years (550 to 539 B.C.). He took Media in northwestern Iran, the Lydian kingdom ruled by Croesus in modern-day Turkey, the Greek cities of Asia Minor, and the Babylonian Empire in Mesopotamia. Under Cyrus, the Persian Empire became the hegemonic power in the East. Despite beginning his reign as a vassal king subject to the Median Empire, which he would later conquer, Cyrus was fierce and effective in battle. But he has also gone down in history as a humane leader and liberator who respected the customs, laws, and religions of the peoples whose lands he conquered. This aspect of his kingship was lauded in the ancient world and has defined his portrayal through the centuries.

According to Herodotus

Cyrus, founder of the Achaemenid Empire, usually appears in Greek sources as an exemplary ruler and clement king, an image backed by Babylonian and Hebrew sources. In the writings of Greek historian Herodotus, around a century after Cyrus’s death, Cyrus is depicted as benevolent, brave, and on good terms with his soldiers. And it is Herodotus who provides one of the most complete accounts of Cyrus’s origins, albeit including some elements that are clearly legendary. He writes that Astyages, king of Media and grandfather of Cyrus, had a dream in which Cyrus seized the throne. Before the rise of the Achaemenid Empire, Persia was subject to Median control for many years as a vassal state. To avoid a future challenge from his grandson Cyrus, who was still a baby at the time, King Astyages ordered his general to kill the infant. But instead, the general took pity on the baby and secretly gave him to a family of humble shepherds to raise. As the young Cyrus went through childhood, he stood out for his daring nature and leadership. This eventually led Astyages to discover his true identity. A conflict later ensued between the Persians under Cyrus and the Medes under Astyages, and the Persians won.

Herodotus describes how Cyrus, having decided to rebel against the Medes, needed to gain his soldiers’ commitment. So he gave them a task. He ordered the men to spend all day clearing a field of thorny plants. The next day they returned to find a great feast awaiting them. When they had eaten their fill, Cyrus asked which they preferred: to remain enslaved and exploited by the Medes, which was akin to clearing a field of thistles, or to throw off the Median yoke, attain freedom, and enjoy abundance by creating their own empire. This episode gives an insight into how skilled Cyrus was at motivating his soldiers for war, a factor that would be key in his future conquests. Herodotus writes that the Persians felt such affection for Cyrus that they thought of him as a father figure. Plutarch, another Greek historian, corroborates the claim: “The Persians love those with aquiline noses because Cyrus, the most beloved of their kings, had a nose of that shape.”

Herodotus does, however, mention Cyrus displaying some worrying behavior at the end of his life. One example is the strange punishment the king inflicted on the Gyndes River (possibly the modern-day Diyala River) after one of his horses drowned in it. Cyrus allegedly set his army to work for a whole summer dividing this tributary of the Tigris into 360 channels as revenge for the horse’s death. Given that the Persians believed watercourses were sacred, this was a sacrilegious act as well as an irrational one.

Herodotus also relates it to the dramatic circumstances of Cyrus’s death. He records that the king was killed while fighting against the Massagetae, a nomadic people of Central Asia ruled by Queen Tomyris. Cyrus’s body was then defiled by Tomyris as revenge for her son’s death. According to Herodotus, this last military campaign was driven by Cyrus’s arrogance and led to him being punished by the gods.

Herodotus uses this narrative to reflect on the degeneration of Persian power. He claims that as Cyrus’s conquests stacked up, he and his people began to abandon the austerity and self-discipline of their origins in favor of opulence and ease. According to Herodotus and later Greek authors, it was this shift in behavior that triggered the decadence of the Persian Empire and the corruption of its great kings.

Cyrus grants freedom to the Jewish exiles held in Babylon in this 19th-century engraving by French illustrator Gustave Doré.

Alamy/ACI

A romanticized vision

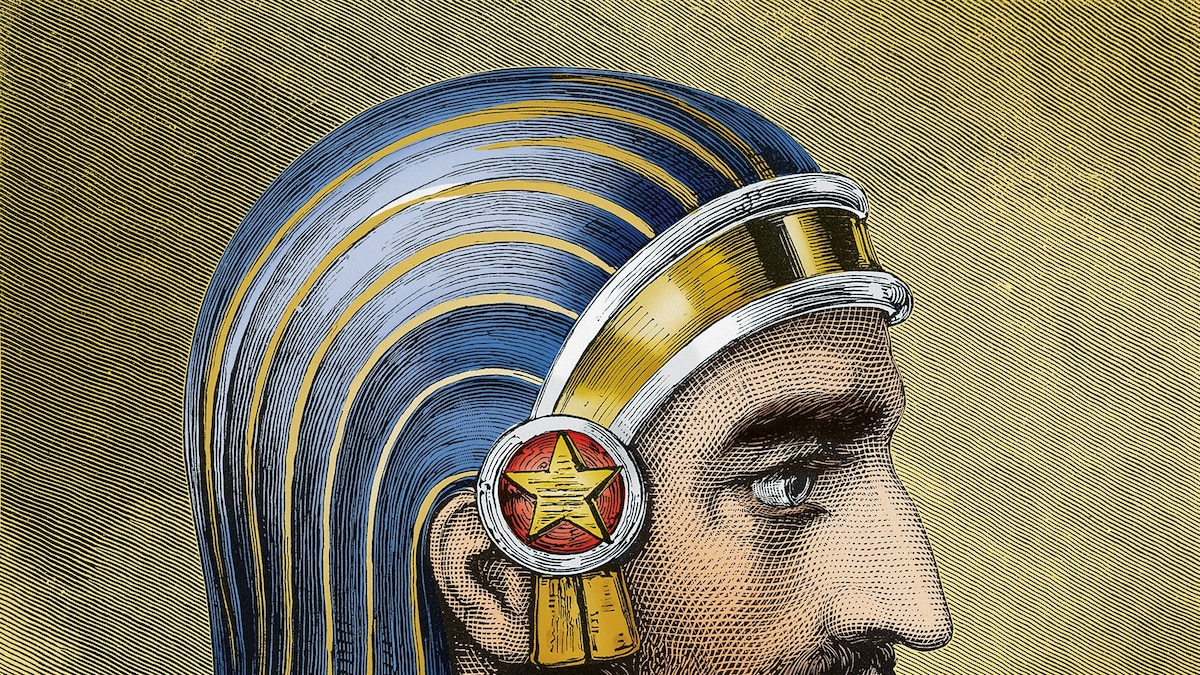

Greek historian Herodotus, depicted in this fifth-century B.C. bust, wrote about Cyrus in Histories, circa 425 B.C.

DEA/Album

The Cyropaedia is an idealized biography of Cyrus as the philosopher king, compiled by Xenophon, who was an Athenian historian and philosopher who lived between the fifth and fourth centuries B.C. Xenophon, who supported the idea of a monarchy, used Cyrus as a figure to project his vision of the ideal monarch. The Cyrus portrayed in the Cyropaedia should be read as a largely fictional character, created by Xenophon to reflect his own political views. To write the Cyropaedia, Xenophon drew on the works of earlier Greek authors such as Herodotus, but he also had firsthand knowledge of the Persian world. From 401 to 399 B.C. Xenophon participated in the expedition of the Ten Thousand as a member of an army of Greek mercenaries recruited by another Cyrus of the Achaemenid dynasty, Cyrus the Younger. This Cyrus was rebelling against the authority of his brother, King Artaxerxes II. During the campaign, Xenophon must have heard accounts of the life of Cyrus II, embellished by Persian tradition. Xenophon depicts Cyrus the Great as a studious king, just, generous, affectionate with his men, brave, and eager for glory. Cyrus the Great as portrayed by Xenophon matched the cliché of the great king that was typical in popular Persian stories of the day: He was handsome and strong, and his kingly qualities had been evident from childhood. According to Xenophon’s account, Cyrus the Great piously fulfilled all his religious duties, thereby winning favor from the gods. Put simply, the great king “excelled in governing” because “so very different was he from all other kings.” This positive view is supported by the historian Diodorus of Sicily, who writes that Cyrus “was pre-eminent among the men of his time in bravery and sagacity and the other virtues; for his father (Cambyses I) had reared him after the manner of kings and had made him zealous to emulate the highest achievements.”

Many of Cyrus’s conquests, such as Media and Lydia, are often ascribed to his military expertise. The fall of Babylon, however, is also accredited to King Nabonidus’s failure to honor the city’s chief god, Marduk, causing dissension and the opportunity for invasion. Cyrus’s religious tolerance, abolishment of labor service, and the freeing of Jews garnered him praise.

(We know where the 7 wonders of the ancient world are—except for one.)

Xenophon claims that the great king exhorted his subjects, saying: “Next to the gods, however, show respect also to all the race of men as they continue in perpetual succession.” This was an indication of Cyrus’s humanitarian qualities that so exalted him in the eyes of the Greek historian. The Cyropaedia contains a variant account of Cyrus’s death: He did not die in combat, as Herodotus claimed, but in the palace surrounded by his sons. Xenophon adds that death came while Cyrus was immersed in a conversation about immortality and urging his listeners to lead dignified and pious lives. This scene is reminiscent of the death of Socrates, Xenophon’s mentor, who died by suicide surrounded by his friends and followers after his fellow Athenians condemned him to death.

Plato and Ctesias

The philosopher Plato, another disciple of Socrates, also makes reference to Cyrus, again portraying him as an exemplar of justice and wisdom. According to Plato, the Persians under Cyrus maintained the correct balance between servitude and freedom. This enabled them to become masters of an empire. But after Cyrus’s reign, this balance was upset as his successors succumbed to the love of luxury, decadence, and the pleasure of the harem, which eventually led to the empire’s collapse.

Not all Greek authors are so favorable to the figure of Cyrus, however. Ctesias, for example, was a Greek physician and historian who, in the fifth and fourth centuries B.C., served at the court of the Persian king Artaxerxes II. There, Ctesias says, he was able to consult the royal annals of the Achaemenids directly. The information Ctesias conveys about Cyrus is characterized by hostility and suspicion and contrasts with earlier accounts. According to Ctesias, Cyrus’s origins were not as noble as Herodotus and Xenophon indicate. He claims that the future monarch was born the son of a bandit called Atradates and a goat herder called Argoste. Cyrus’s humble, nomadic background framed him as a barbarian at odds with the civilized life of Greek society. His rise to kingship was not too praiseworthy either. According to this account, after rebelling against the Median king Astyages, Cyrus allegedly killed the defeated king’s son-in-law Spitamas and married the king’s daughter Amytis. In other words, Cyrus was a usurper, with no birthright to the Median throne. Ctesias also has a different story of Cyrus’s death, claiming that the king died of a thigh wound sustained during a confrontation with the Derbices, a people from eastern Iran.

You May Also Like

(History’s first superpower sprang from ancient Iran.)

A less than pious king

Finally, Isocrates, Athenian orator and politician, also mentions Cyrus but does not consider all his actions to be pious or just. Regarding the war between the Medes and Persians, Isocrates writes that after Astyages, king of the Medes and grandfather of Cyrus, had been defeated, Cyrus had unjustly ordered his death. This account should be seen in context. Isocrates was a defender of the Greeks’ union against the Persian threat. His views on Persia may have influenced his negative depiction.

Despite a few detractors, Cyrus II was the Achaemenid king treated best by Greek tradition. He was generally presented as an ideal monarch, a model of the wise, pious, and just sovereign. According to Greek tradition, the decline of the Persian Empire began with his son, Cambyses II. From then on, according to the Greek sources at least, Persia would be ruled by cruel, impious despots. Xerxes I, the Achaemenid king who dared to attack continental Greece in 480 B.C. during the Greco-Persian wars, was foremost among these. The Greeks’ biased portrayal of the Persian monarchy has influenced ideas about the Achaemenids up to the present day.

(Age-old secrets revealed from the world’s first metropolises.)

This story appeared in the March/April 2025 issue of National Geographic History magazine.