Now Reading: When mother squid die after sex, an unexpected ally helps their babies

-

01

When mother squid die after sex, an unexpected ally helps their babies

When mother squid die after sex, an unexpected ally helps their babies

An opalescent squid’s experience of motherhood is almost cruelly brief. Towards the end of her life, she engages in a dramatic reproductive spectacle where, under the glowing moon, a mating frenzy draws large numbers of Doryteuthis opalescens into the shallows to spawn. It’s a relentless, disorienting ritual characterized by clouds of banana-sized cephalopods flashing red arms—a mating signal—and blending together in a haze.

“The seabed and canyon slope, normally a stable point of reference, shifted underneath us as the squid melded in a living current,” says underwater photojournalist Jules Jacobs, who was there to document the story of the mating phenomenon off La Jolla Shores, California, in an event that can be witnessed at night, typically once a year, if at all. The mating event itself is unpredictable in terms of when and where it happens, but in general opalescent squid are most prevalent between the Baja Peninsula in Mexico and Monterey Bay, California, though they extend to British Columbia, Canada.

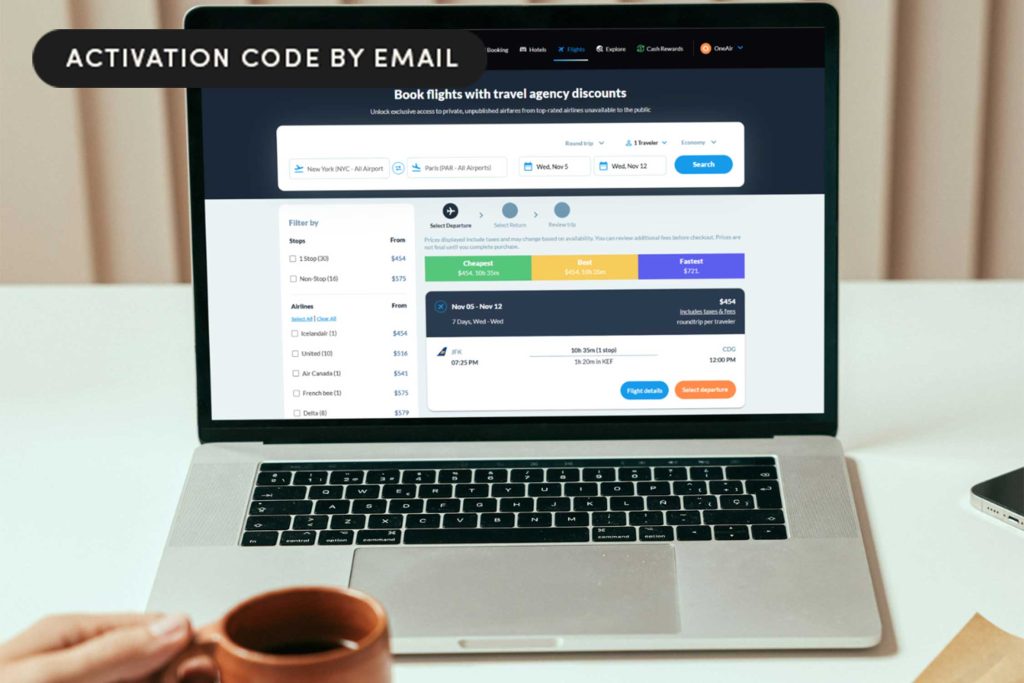

The red worms make their way into the eggs, ready to eat the jelly-like matrix. Their work makes it easier for the baby squid to hatch.

Photograph By Jules Jacobs

Males, sometimes several of them, mate so aggressively with the inundated mother that they weaken her body. The brutal underwater brawls end in the mother and her mates drifting down to their death, bodies littered among the brood. The mother’s offspring are contained in tubular white capsules that make up vast, luminous underwater fields. They sway gently in the current, clusters of them covering the sandy slope of La Jolla Canyon.

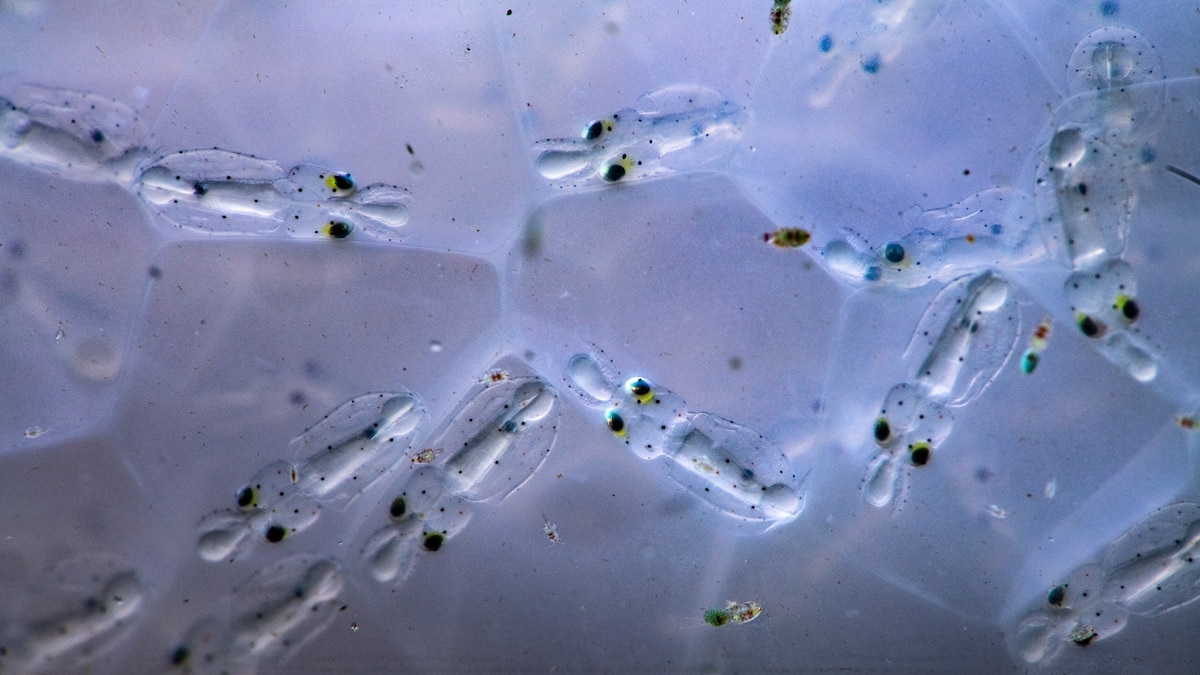

These sheath-like capsules are deposited with up to 300 of her developing squid embryos. The marble-like eggs transform into paralarvae, or baby squid, that look like gelatinous orbs with beady little eyes that crowd together in the sac. The eggs are many layers thick, seeded with bacteria left behind by the mother, which make them generally unpalatable for predators like Dungeness crabs and Bat stars. Other than that line of protection, the squid eggs are on their own in the barren sea floor, waiting to hatch.

In such micro worlds, small invasions are easy to miss. From the depths of the sand emerge the marine worms Capitella ovincola, who make their way to the eggs. In a move that’s reminiscent of Bruce Lee’s 1-inch punch, the worms make their heads pointy, then flat, as they jab a hole into the egg and wriggle inside.

Though the purpose of the break and enter seems dubious, the worms aren’t here to harm the developing babies. They’re here to act as midwives—that is, to help, says Lou Zeidberg, lecturer at California State University, Monterey Bay, who studies marine biology. While the worms leave the eggs themselves alone, they eat the gelatinous matrix in between each one, called the chorion—a honeycomb-like structure that separates the hundreds of embryos. When they do this, it becomes easier for baby squid to hatch. “Once there are a few punctures in a capsule created by the worms, saltwater seeps in and expands the whole capsule, thus stretching the capsule sheets thinner,” says Zeidberg. Along with better oxygenation, an egg capsule with worms gets soft and squishy, whereas one without them is much more rigid. The paralarvae have an easier time breaking through a softer egg casing where some of the gelatinous matrix material has already been eaten.

The eggs provide nutrients and shelter for the worms, and in turn, the worms facilitate an increased hatch rate for the squid embryos, suggesting a symbiotic relationship between the organisms. This symbiosis results in approximately 17 million extra squid per “run” that could hatch. “Hatching is just the beginning. The life of a baby squid is perilous, and it takes a lot to make it to adulthood,” says Zeidberg. Baby squid have a high mortality rate and deal with a medley of challenges before reaching adulthood, from high predation rates to difficult ocean conditions.

On the slope of La Jolla Canyon in California, a mother squid dies after laying her eggs. In the foreground, a group of red Capitella worms waits.

Photograph By Jules Jacobs

The first to document this symbiosis between the squid and the worms was Olga Hartman, an American invertebrate zoologist, in 1944. And while some experts like Zeidberg see the worms as midwives now, others have portrayed them more as opportunistic squatters. In a 2002 paper, scientists found that after worm activity, the thickness of the gelatinous matrix was reduced, exposing the eggs and causing premature deterioration. When the squid hatched, they had “visible external egg yolk sacs and limited swimming capability, leading to their death shortly after hatching.” In short, the paper argued that worm activity harms the egg sheaths, causing the squid to hatch prematurely and increasing their already precarious mortality rate.

You May Also Like

“A lot of symbioses live on a continuum and can slide from being beneficial to harmful once the worm infestation gets high enough,” says Zeidberg. He suggests that differing levels of worm infestation in the squid eggs likely led to the varied interpretation.

Whether the worms serve as midwives or squatters, their presence reflects the broader health of the ocean. “Capitellaworms are well-known to have explosive population growth when there’s pollution in the water,” says Greg Rouse, professor of marine biology at the Scripps Institute of Oceanography. This worm proliferation could either be a welcome addition to developing paralarvae, helping them hatch, or a tax on their survival, causing them to hatch when they’re still underdeveloped. The Capitella worms are often called pollution indicators, proliferating when there are too many nutrients in the water. Their bright red coloring is because of hemoglobin, allowing them to tolerate the low oxygen levels.

The underwater world is filled with these hidden symbioses, and however scientists interpret the role of Capitella ovincola, one thing is clear: The mother squid’s brood is not alone after her death. Tiny worms are there, ushering them into the world.