Now Reading: Where should archaeologists dig next? The winners of this OpenAI contest can tell them.

-

01

Where should archaeologists dig next? The winners of this OpenAI contest can tell them.

Where should archaeologists dig next? The winners of this OpenAI contest can tell them.

Buried deep within millions of square miles of dense Amazon rainforest may lie tens of thousands of hidden archeological sites, where stone tools and rock paintings are testaments to civilizations that existed as far back as 13,000 years ago.

But the thick forest sprawled across nine countries and home to hundreds of Indigenous groups today, is too vast and often difficult for archeologists to physically survey for hidden sites. Increasingly, researchers are looking to newer technologies like Artificial Intelligence and machine learning for help.

That’s why two archaeologists recently collaborated with OpenAI, the company behind ChatGPT, to judge a public competition encouraging tech enthusiasts to explore large troves of satellite images and remote sensor data for signs of undiscovered archeological sites.

The winning three-person team of the “OpenAI to Z Challenge,” announced Thursday, found 67 distinct patches across the Amazon, each measuring about a square mile, that they think could contain historically valuable ancient sites and provide potential starting points for field exploration. The judges included Egyptologist Sarah Parcak and Mesoamerican archaeologist Chris Fisher.

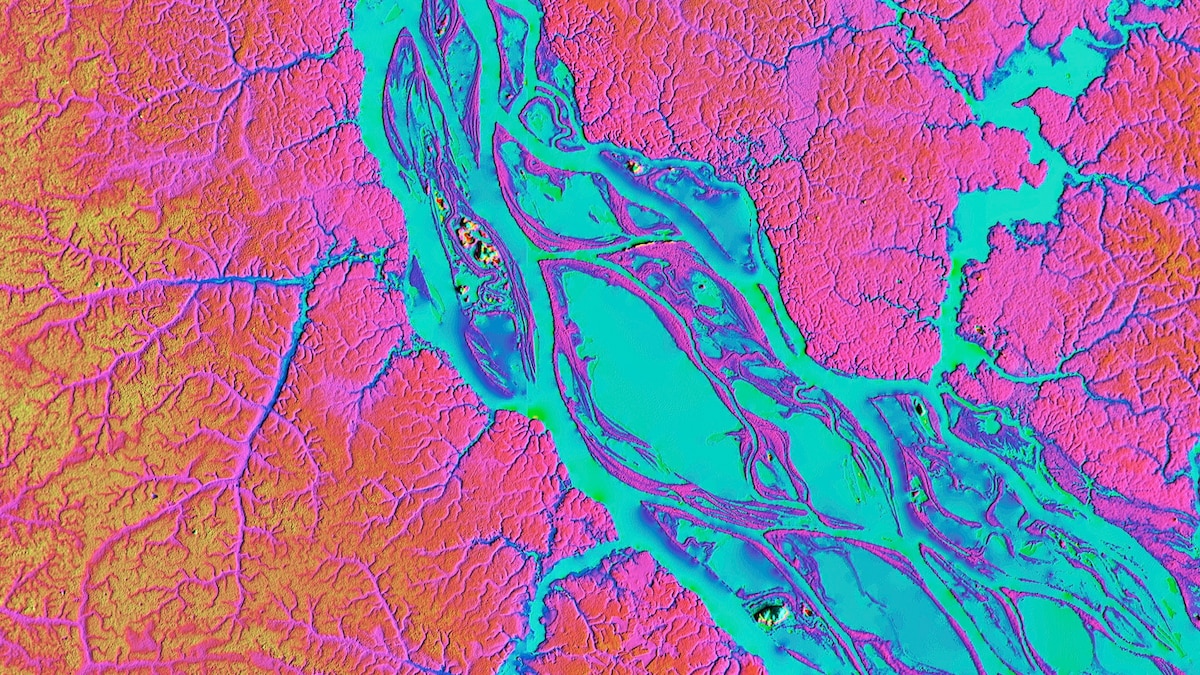

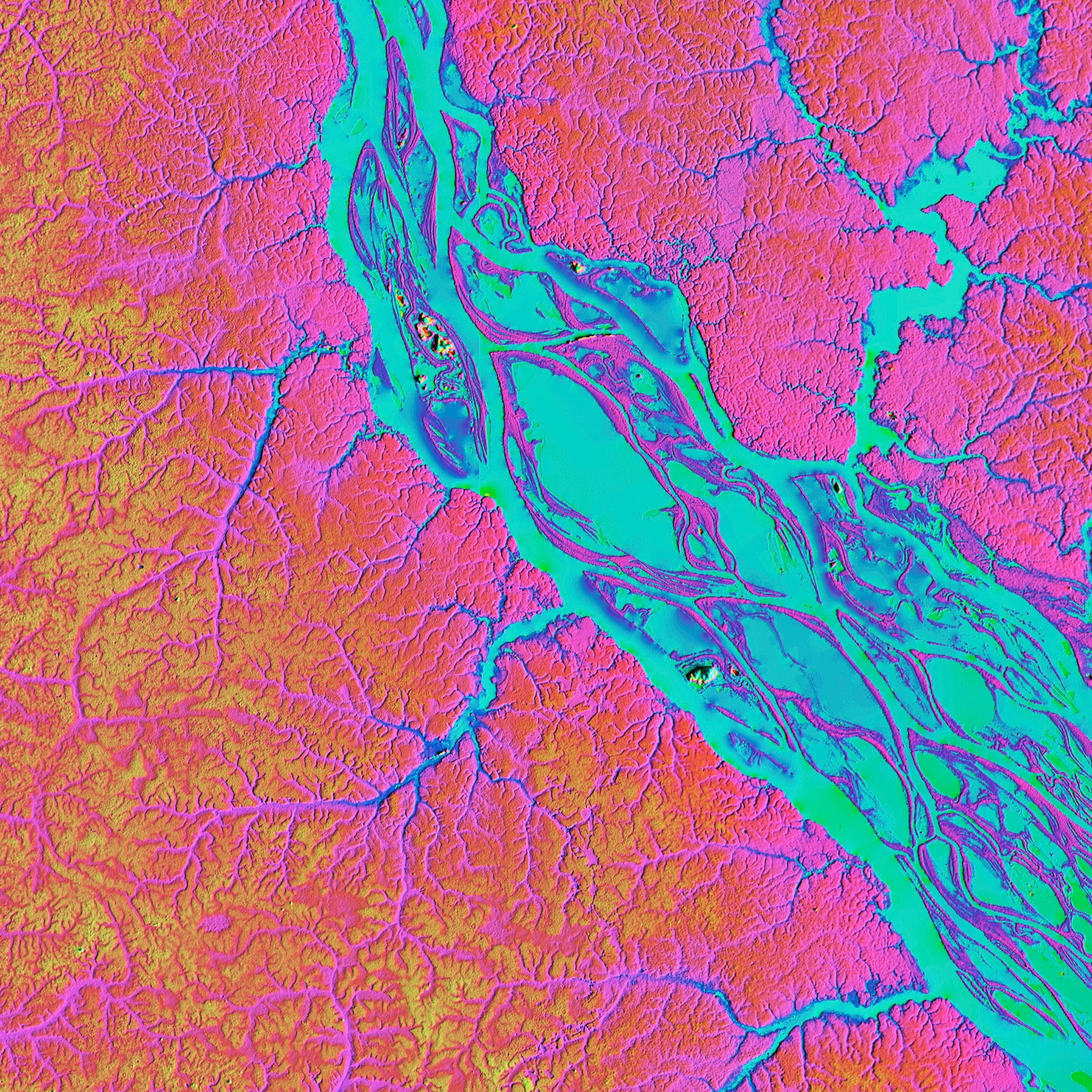

The winning team, which calls itself “Black Bean,” trained deep learning models on several publicly available datasets, including remote sensing LiDAR data and satellite images from Google Earth Engine and NASA’s digital elevation models, among others. The team says they then used OpenAI’s GPT-4o model to learn the pattern of known archeological sites in the Amazon rainforest and compare them to unexplored swaths of the Amazon, mainly in Brazil. It then highlighted dozens of coordinates for future exploration.

Many of the areas they identified appeared to be clustered along bodies of water.

“Our results actually make sense on a common-sense level,” says Yao Zhao, a member of the winning team who is currently a software engineer at Meta, and was on a career break during the competition to learn more about AI applications. Ancient civilizations, after all, tended to flourish near accessible water sources.

Being able to quickly churn through millions of square miles of geographic data within a few weeks could make it easier for archeologists to find patterns without relying on groundwork first, he adds. The first-place winners received a $250,000 cash prize and credits to use premium OpenAI products.

LiDAR satellite image showing the Rio Negro, one of the largest tributary rivers of the Amazon. The winners of the OpenAI archaeology challenge identified 67 distinct square mile patches they recommend explorers search to find potential ancient sites. Many were near water.

Photograph by Matthew Hurst, JAXA/Science Photo Library

Adding AI to the archaeologist’s toolkit

Machine learning isn’t a completely new tool to explorers of the ancient world. Parcak, an archeologist at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, has used satellite images, thermal imaging and LiDAR, which employs planes or drones to emit pulses from sensors and observe their return, for a few decades in her exploration of Egypt, Tunisia and other countries.

Those imaging tools and techniques, combined with machine learning trained to find patterns in data, have helped her uncover thousands of previously unknown settlements and tombs within known archeological sites. But newer AI models could build on those uses by looking beyond established archeological targets, turning up entirely new areas for archeologists to investigate, she says.

Many sites are disappearing across the world as sea levels rise, vegetation spreads or recedes, and as humans build and migrate, abandoning or destroying valuable historical records.

You May Also Like

“We have a very limited period of time to document the Earth and everything as it exists now before it fundamentally changes,” says Fisher, an archaeologist at Colorado State University.

Parcak and Fisher say the judges selected team Black Bean because their approach was easy to replicate, and because of their creative method of merging together several public data sets in their analysis.

“You could just about submit their PDF overviews to the Journal of Archaeological Science,” says Parcak. “The process ended up closely mirroring the one that remote sensing people do.”

Ethical challenges and Indigenous concerns

While Parcak and Fisher think competitions like these can democratize archeology, allowing non-experts across the world to help preserve history, other experts warn that they could invite exploitation.

After OpenAI announced the challenge earlier this year, critics pointed out that the company had not consulted Indigenous groups in the Amazon living near the target area who might have different opinions on how their archeological sites and heritage should be treated. Those individuals might also object to untrained technologists trawling detailed geographical data of their homes, community and history.

OpenAI has also drawn criticism for popularizing generative AI, the subset of artificial intelligence that can create its own content, and that has prompted larger questions around ethical standards in the industry. Parents of a 16-year-old boy who was confiding in Open AI’s free ChatGPT tool before his death by suicide have sued the company for endangering “minors and other vulnerable users without safety guardrails,” according to the lawsuit. (Open AI has responded to the incident in a blog post, where it said it was convening a mental health advisory group and “continuously improving how our models respond in sensitive interactions.”)

After the competition was announced, Brazil’s Indigenous ministry demanded that OpenAI halt the competition until it clarified its aims, according to Science. A spokesperson for OpenAI told National Geographic that it is continuing to follow local laws and engaging with local institutions so that all the data participants in its competition used was already public. Parcak added that the datasets offered to competitors did not include any areas known to contain uncontacted Indigenous groups.

The winning team told National Geographic that they plan to share their work with archeologists and geologists to refine their predictive model, but that they don’t have plans yet to visit the 67 sites in person. “Before we do something, we’d do a very careful consideration of how not to interrupt the humanity in the area,” says Zhao.

Parcak and Fisher say they expect to see more private companies, particularly those focusing on AI and machine learning, launching similar competitions as federal funding for archeology dries up.

“Our field has to ask itself some uncomfortable questions about where they’re willing to go to get support,” even if it means working with Silicon Valley tech titans, she says.

Still, Parcak adds, she doesn’t think AI is going to replace archaeologists. “It’s kind of scaling what remote sensing scientists have been using for 50 years.”