Now Reading: Why Rome’s dolphins are fighting each other

-

01

Why Rome’s dolphins are fighting each other

Why Rome’s dolphins are fighting each other

Rome, the Eternal City, is revered for its history, art, culture, and food. Yet, few people know that less than an hour away, where the Tiber River flows into the Tyrrhenian Sea, there’s something that makes the area even more unique: a population of around 500 bottlenose dolphins.

Now, a recent study shows that the dolphins are not only sick, but they’re fighting over food—and it’s due to human activity.

The “Capitoline dolphins,” as researchers have named them, have inhabited the coast outside Rome for thousands of years, as shown by mosaics from the archaeological site of Ostia Antica that depict the dolphins stealing fish from fishermen’s nets 2,000 years ago. Yet they’ve only recently been closely studied, beginning in 2016.

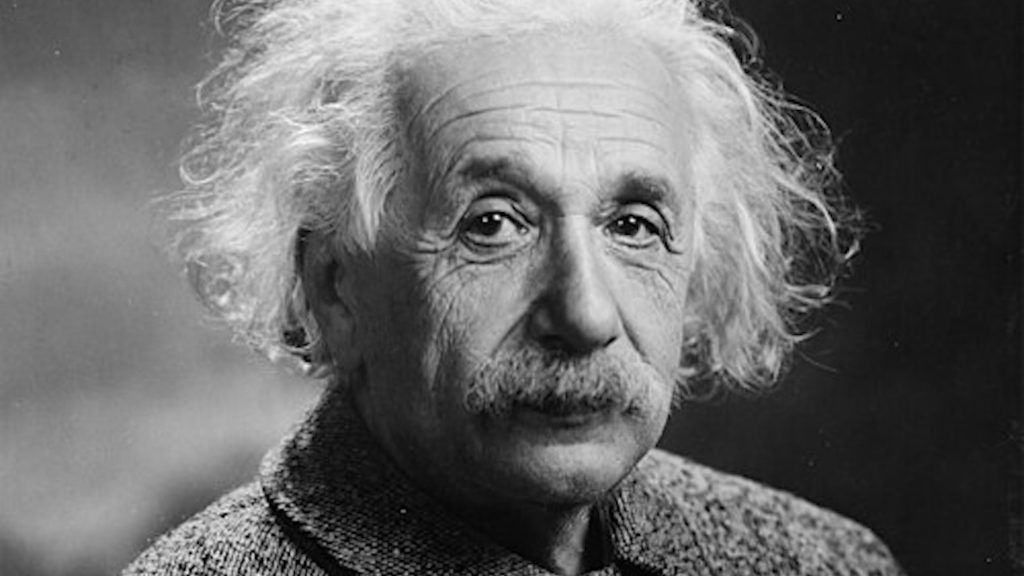

Two male dolphins have an aggressive encounter in the sea outside Rome.

Photograph By Daniela Silvia Pace, CoNISMa-Tor Vergata University of Rome

It’s not unusual for Rome’s dolphins to display signs of fighting.

Photograph By Daniela Silvia Pace, CoNISMa-Tor Vergata University of Rome

Around 500 dolphins spend some of the year in the area, while about 100 are permanent residents—mostly females and their offspring who live near the mouth of the Tiber River, where food is most abundant. This makes the area an important breeding site, where males are attracted each year to mate.

Daniela Silvia Pace, a researcher at the Sapienza University of Rome, has studied these dolphins for a decade. She and her colleagues recently analyzed more than 400 photographs taken between 2016 and 2023, depicting 39 individuals of the resident population.

“What emerges is a decidedly worrying picture,” as these animals are subject to so many pressures, she says.

Pace and her team measured and counted marks on the dolphins’ bodies. Analyzing marks on cetaceans is a common technique used by scientists, as it can tell them a lot about their life, their health, and the dangers they’re exposed to.

The result of the new research, published in Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems in April, does not necessarily paint a hopeful picture. “Unfortunately, the situation for bottlenose dolphins in the Mediterranean, including the Tiber River Estuary, appears to be particularly concerning,” says Bruno Díaz López, a biologist and director at Bottlenose Dolphin Research Institute, who was not involved with the study but found it “very interesting and relevant.”

The analysis revealed that 70 percent of the residents studied showed signs of malnutrition, such as visible ribs. “This is strange, because we are in an area rich in food,” says Alice Turchi, a PhD student in environmental and evolutionary biology at the Sapienza University of Rome and author of the study. Turchi and her colleagues believe that the lack of food might be due to overfishing.

“The fact that most of the population is undernourished is a strong alarm bell,” adds Pace.

You May Also Like

In the study, the lines and ropes used by fishermen had left marks on half of the dolphins’ bodies, and amputations were present as well. Nearly all, or 97 percent, of the dolphins had a skin disease, which didn’t come as a shock to the researchers.

“It is not surprising,” says Turchi, because the water is tainted, mostly due to pollutants carried by the Tiber River into the sea, as well as wastewater from boats passing through. “Pollution can promote immunodepression and cause animals to get sick,” Turchi says.

In another distressing development, researchers also found evidence of fighting. They analyzed teeth marks caused by interactions with other dolphins, which were universal across the population. While these marks are sometimes normal for dolphins, as they can bite to communicate dominance during mating competitions or to establish social hierarchies, this population showed an unusually high number. The researchers believe that this may be due to competition for dwindling food resources.

Threats to bottlenose dolphins around the world

López, from the Bottlenose Dolphin Research Institute, says the findings on the Capitoline dolphins’ health “are consistent with what we observe in many coastal bottlenose dolphin populations worldwide.”

“These populations are exposed to continuous and intense pressure from human activities, ranging from fisheries and maritime traffic to pollution and habitat degradation,” he notes.

For example, he says, “in Galicia, on the Atlantic coast of Spain, we see similar patterns of skin marks related to both natural and anthropogenic factors.” Similarly, he says, “studies from other regions—such as Sarasota Bay in the United States or various sites in Australia—also report high frequencies of marks linked to social interactions, fishing gear, boat strikes, and skin diseases.”

While bottlenose dolphins are an adaptable species and can show great resilience, the researchers are worried about the future of this population. The area is currently “unmanaged,” says Turchi, meaning that almost no conservation actions are carried out to protect this slice of coast. “There is a need to carry out interventions to safeguard this population, which is unique.”

The team says that it would be necessary to establish a Site of Community Importance, which would help the conservation of this population and the whole rich ecosystem found off this coast. But the process to establish such a site is “very complex,” says Pace, and would need to run up the political chain.

The researchers hope that making this population known to the general public could be a step in the right direction to ensure that politicians will be more motivated to implement conservation actions aimed at protecting the area.

“It is important to take into account that this area is important for this species, and it is also important for our species,” says Turchi. “We should try as much as possible to reconcile human exploitation with the conservation of biodiversity.”